“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.”

—

Octavia

E. Butler

“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.”

—

Octavia

E. Butler

9-10 minutes or the time it takes to boil an egg.

In her performances, videos, and installations, Patty Chang offers subtle, surprising examples of how kinship manifests at multiple scales: within one’s body, with another person, with an audience, with water and land. We asked her to ruminate on how ritual, gesture, and touch relate to the caretaking needed to establish and preserve these various connections. What emerged was a clear and persistent willingness to work through discomfort or fear in order to arrive at a new understanding or relationship.

How do you define kinship and would you consider it a main concern in your work, or the result of it? Both? And, why?

Patty Chang: I think kin is a relation to something or someone. I also think of it as an alignment, perhaps an affinity, something mostly invisible or perceived only through a commitment that holds you together. The phrase next-of-kin is a funny one. Next-to-kin makes more sense to me. Next-of-kin kind of sounds broken. Which is maybe why we use it. Broken language sometimes is more appropriate. I never used the word kin, though the sentiment is definitely part of my work. I see the usefulness in bridging scales of relating and of creating connection that is mostly invisible or perceived only through a commitment that holds you together. It may seem easier to define family as kin, or other people as kin, and I take that as a starting point to make relations with others. In my project The Wandering Lake, I am trying to bridge different scales of relating to create tighter bonds between entities that may seem at odds — emotional, personal, institutional, governmental, and terrestrial scales.

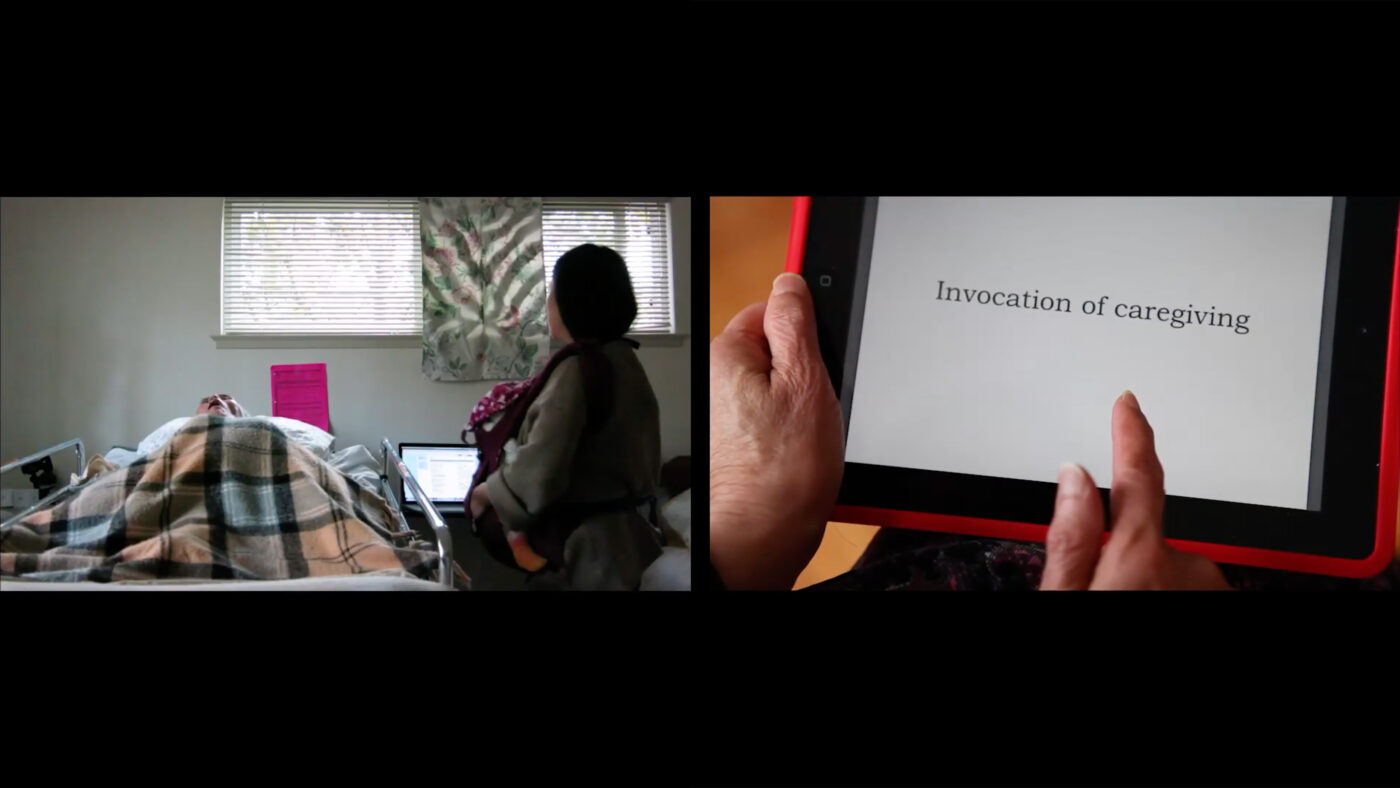

[ID: Photograph of two film stills. On the left, Patty’s father lies on his bed under a plaid blanket, while Patty stands by his bedside, holding an infant. On the right, hands hold an iPad with the words “Invocation of caregiving” in large serif type.]

If everything seemed comfortable, is the discomfort being deposited elsewhere, possibly at someone else’s expense? Tension is a link that holds things together, connecting them.

Kinship sounds like a nice thing, in fact is a wonderful thing, but it’s not without its discomforts, and I think your practice exemplifies that tension really successfully. You sort of offer these possibilities of connection through difficult or mournful situations. With that in mind, I was wondering if you could elaborate on something you said in another interview about how “sharing an awful experience with another person binds you together.” Why are you drawn to illuminating moments of loss (whether personal, environmental, or otherwise) as a means of (re)connecting?

Patty: If everything seemed comfortable, is the discomfort being deposited elsewhere, possibly at someone else’s expense? Tension is a link that holds things together, connecting them. That quote refers to In Love, the performance video where I eat a raw onion with my mother and my father separately. The video is played backwards and so we start kissing and crying until the onion emerges intact. The parent child relation is a primary one and informs how one experiences relations with others as well as relations to the self. Loss is constantly happening at lesser and greater levels, just like the discomfort. Recognizing and giving space for it allows for us to hold complex feelings and ambivalent feelings at once. I think there is also an opportunity in the recognition that something different could emerge or take place — that the relation could be recalibrated.

[ID: Holding a large sponge in orange-gloved hands, Patty stands on a rocky shore facing away from the camera. In front of her, part of the body of a sperm whale is visible floating on the water, as large as an ice floe. The horizon meets a grey sky in the distance, and gulls sit on rocks further out in the water.]

In your most recent projects Milk Debt and The Wandering Lake: 2009–2017, there’s a recurrence of ritual and ritualization. I also love the videos Invocation & Que Sera Sera for encapsulating what caretaking one’s parents feels like, and the video of you washing a dead sperm whale to mourn and honor it. Could you talk about how ritual, or even repetition, inform your practice or way of processing things?

Patty: Ritual is an organization of everyday life and a marker of time passing. My performance comes out of ritual and gesture. It is active, a verb. I love Jill Casid’s conjugation of landscape. I thought about how ritual activated the land in The Wandering Lake. I also think it’s practical. Because part of my work involves going to unfamiliar places (mostly geographies but also emotions), I use ritual as a way to ground myself and not get lost in the anxiety of the unknown, which allows me to respond to what’s happening around me. The ritual is balanced with the contingent.

[ID: A Kirkland brand water bottle recreated in glass lies on its side with a piece of tan-colored tape around the label. Part of the side of the bottle has been removed, leaving an open space for liquid to enter.]

Touching can comfort as well as provoke, so the tension is never far away.

A key part of these care rituals is activating the body, as evidenced in breastfeeding and your urinary devices. You once described ritual as “a way of caring and connecting and at the same time letting go.” I was hoping you could share more about this: How have physicality and gesticulation shaped your understanding of care?

Patty: Both physicality and gesticulation are informed by touch. Touch is comforting. The simple gesture of wiping with a sponge signals an act of cleaning and caressing simultaneously. The swiping of the iPad is also comforting perhaps because nothing lasts forever. Touching can comfort as well as provoke, so the tension is never far away.

[ID: A still of a film projected on a gallery wall. A woman with dark hair sits on a tree by a river with the front of her yellow dress open. Addressing the camera, she holds breast pumps up to both of her breasts. The subtitles of her speech read “Afraid that when I dream certain things will become a reality.”]

You’ve noted that the phrase “milk debt” comes from the concept in Chinese Buddhism that a child can never repay the mother for raising and feeding it with her breast milk. The word debt tends to feel negative, but would it be fair to say that your project complicates that connotation, particularly when it comes to the debt we owe each other? What do you think is the debt we owe each other most right now?

Patty: Debt implies obligation and if this obligation upholds a tradition that is hurtful then this is a problem. I want to think about debt as a relation that is realigning or healing. That is a really good question, what is the debt we owe each other?

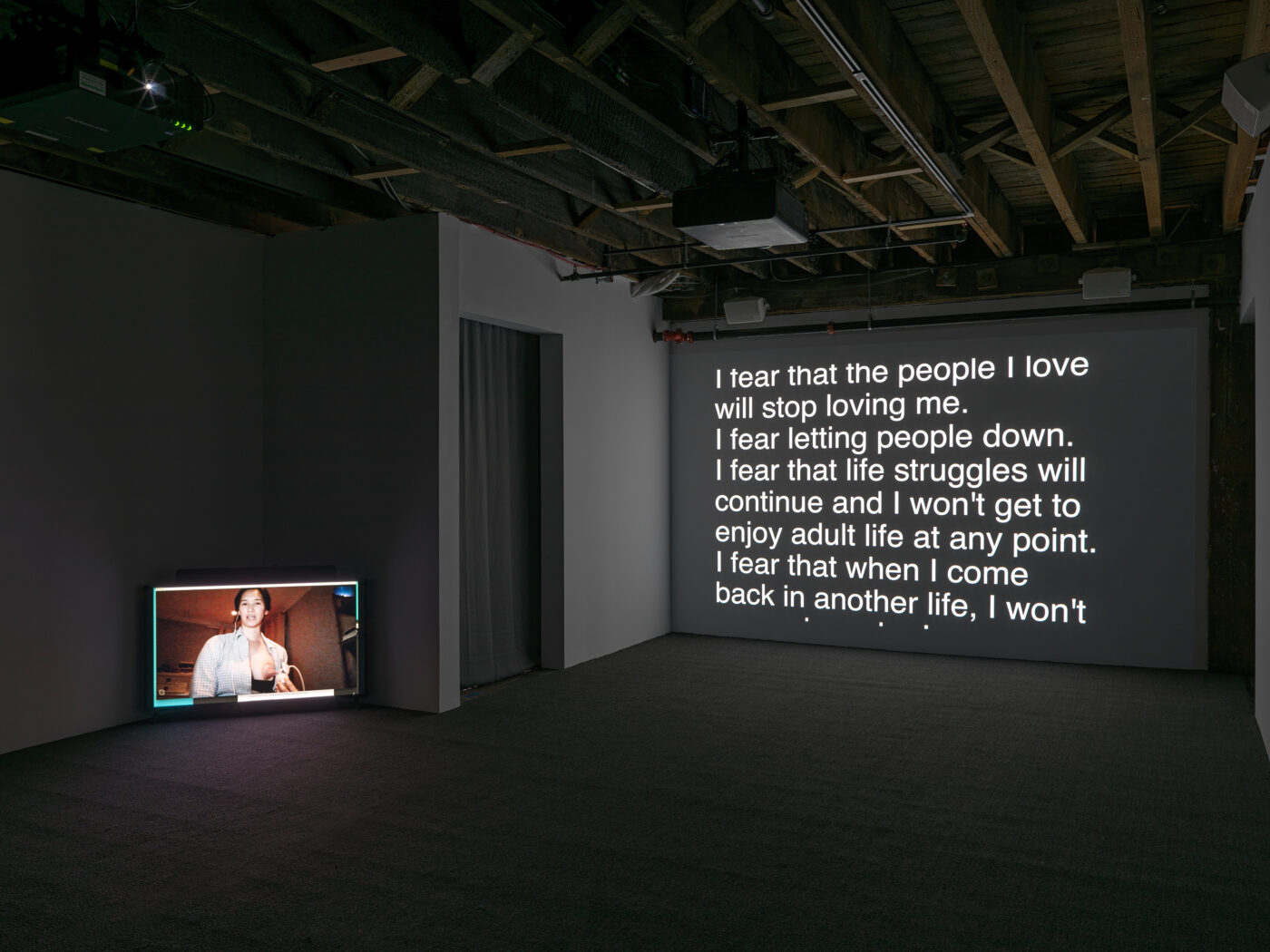

[ID: Installation view of a small screen and text projected on a nearby wall. On the screen, a woman in a checkered button up shirt holds a breast pump to her left breast. The text on the wall reads “I fear that the people I love will stop loving me. I fear letting people down. I fear that life struggles will continue and I won’t get to enjoy adult life at any point. I fear that when I come back in another life, I won’t…”]

Both accumulation and release are rendered visible in Milk Debt through the act of pumping breast milk. Similarly, the entire project is a release and representation of accumulated ideas. How do you know when you’ve finished accumulating material for a project and is the form of its “release” something you plan for in the early stages or at the end?

Patty: I love the rhythm of accumulation and release. I think that is an apt way to look at my art making process. I often start accumulating things that, at a later date, I need to figure out how an audience would experience. Like for The Wandering Lake, I accumulated information and experience in places outside of an art space and I wanted to figure out how the artwork would retain the physical, gesticular, and bodily experience. This didn’t start happening until I had already accumulated most of the performances, images, documents, and objects. Scale was a way to organize the experience, from landscape to consciousness. Slowly over time as the viewer walks through the installation the outside is embodied within.

[ ID: Patty, an Asian American person, looks at the camera in front of a rocky shoreline. Patty is wearing large red-brown sunglasses with her hair tied back into a loose bun, a patterned collared shirt, and a cardigan.]

Patty Chang

She // Her // Hers

They // Them // Their

Los Angeles, CA

Patty Chang is a Los Angeles-based artist and educator who uses performance, video, installation, and narrative forms when considering identity, gender, transnationalism, colonial legacies, the environment, large-scale infrastructural projects, and impacted subjectivities. Her museum exhibition and book The Wandering Lake investigates the landscapes impacted by large scale human-engineered water projects such as the Soviet mission to irrigate the waters from the Aral Sea, as well as the longest aqueduct in the world, the North to South Water Diversion Project in China. Her most recent multichannel video project Milk Debt combines the act of lactation with people’s unspoken fears. Her work has been exhibited nationwide and internationally at such institutions as the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Guggenheim Museum, New York; New Museum, New York; M+ Museum, Hong Kong; BAK, Basis voor actuele Kunst, Utrecht; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Chinese Arts Centre, Manchester, England; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Times Museum in Guangzhou, China; and Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden. She has received a United States Artist Fellowship, a Rockefeller Foundation Grant, a Creative Capital Fellowship, a Guna S. Mundheim Fellowship in the Visual Arts at the American Academy in Berlin, a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, and an Anonymous Was a Woman Grant. She teaches at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, CA.