“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” –Octavia Butler

20-25 minute listen, or the time it takes to do a midday stretch.

A CONVERSATION WITH CLEO OUYANG, THEA LUCE, AND EMPRESS WU

Veil Machine’s collective practice delves into the relationships, ethics, and performative aspects of art and sex work. Co-founded by Cleo Ouyang, Thea Luce, and Empress Wu, the collaborative has produced public events, online performances, and intimate salons while fostering imaginative collective spaces. Rejecting the traditional labor paradigm, they embrace sex work as pro anti-work, emphasizing mutual aid and community support. In the following conversation, they speak to their upcoming manifesto that captures their fluid vision, friendship, and confrontation of the false narratives of sex work in our daily lives. Veil Machine emerges as a force exposing perceptions and navigating the porous boundaries of authenticity, reality, and fantasy within their collective practice.

Allie Linn: I would love for you to introduce yourselves and Veil Machine.

Cleo Ouyang: I’m Cleo Ouyang; I use she/her pronouns. I am a dominatrix and sex worker based in LA. I am also currently in school studying art, and I am one of the three co-founders.

Thea Luce: I am Thea. My pronouns are she/her. I’m a grad student and sex worker rights organizer based primarily in New York, although I’m currently in California wrapping up my PhD. I’m one of the co-founders of Veil Machine.

Empress Wu: I’m Empress Wu. My artist name is also MJ Tom. Cultural activist, dominatrix, and sex worker based in New York City, and also one of the co-organizers at Veil Machine. I also do organizing work at Red Canary Song and Kink Out events.

Veil Machine is a sex worker artist collective. The three co-founders that are here — Thea, Cleo, and I — are all interested in the same questions, which have to do with authenticity, reality, and fantasy. [We’re] asking, what exactly happens, when moving from sex worker artist representation and representation in artwork of what sex work is, to then shift into looking at sex work as an ethic, for organizing practices, for performance practices, for artistic practices?

Veil Machine attempts to codify that in some way or examine it and ask that question to different audiences — whether that’s of clients, of people who think that they have a lot of distance from sex workers, and then also of sex workers themselves — to critically examine those various relationships.

[ID: Five femmes (Thea Luce, Natasha Gornik, Ayanna Dozier, Gabriella Garcia, and Monika Rostvold) sit on a stage in front of a projection of the Veil Machine logo. The photo is shot from the back of the room, showcasing a full audience.]

Thea: In addition, one of the ways that we’ve been asking these questions has been different collaborative practices with other sex workers. Whether that’s a group show engaging sex workers to put on a massive event or through the artist salons that we’ve been hosting. We’re constantly thinking about different collaborative, iterative, and imaginative spaces for sex workers and by sex workers.

Cleo: In recent times, some of the work that we’ve been doing has been more private. Blood Money, which was pre-Veil Machine, was a very public event, and then E-viction was our first work as Veil Machine. That was an online, public-facing performance. Since then, a lot of our work has involved members of our collective and trying to develop our thinking with one another, which is a really important part of our work, too

The loveliness of sex work is that you get to create these little otherworlds and glimpses into worlds of fantasy that become reality just from the experience of embodying it. But then, also knowing and understanding that some of that exists either extremely far in the future or in a place that cannot exist.

Thea: I would say that on that note, it does feel like we have different audiences and communities that we’re engaging. There’s a way that Veil Machine exists for sex workers and in sex worker community, and then there’s a way that it exists in public spaces. We didn’t even think about this at first; we just started shifting between the two and recognized that the registers were different.

Recently, we’ve been thinking about what it actually means to be operating on these different levels: to cultivate private sex worker spaces, and to be thinking about a public practice of what it means to do sex worker art. The sex worker-client problem, basically.

Wu: A classic.

Allie: Is that something you have found some solutions for at the moment, or is it the early stages of trying to figure out how to do that separation of these two aspects of your practice or audiences?

Wu: I think that anybody who is attempting to say there is a right way to navigate that — talking on two registers at once, or navigating operating as a worker and speaking to another worker while also speaking to a client — is a con. I think that is always going to be an iterative process for us as a collective, and then also for every single worker, to learn how they want to speak to multiple different audiences and registers.

Thea: We have tried out certain tangible practices. We’ve tried to have private spaces that go along with public events. For example, a public panel with a private salon, or at E-viction when we had a private, invite-only sex worker hangout within the space. Most recently the work that we’re gradually moving towards, probably next year once Cleo and I have finished with our respective commitments this year, would be a project that looks at the ways in which surveillance works.

I actually think that surveillance is an interesting place to be posing this question. We did a performance intensive for sex workers in July, and on the last day of the performance intensive, we did scenes in the hotel lobby to play with what would happen doing these sex worker encounters in a place of heightened surveillance. The sex workers who engaged in those performances knew what was happening, and we were playing with the gap between what they knew and what everyone around us knew. And I think that’s something that we probably are going to explore more in future work.

[ID: Photo of a computer screen, showcasing a split screen Zoom window from Veil Machine’s recent performance intensive. The left window showcases two white femmes on a bed in a hotel room from the perspective of the corner of the room. One, dressed in business attire with black stockings, straddles the other dressed in black. The other window is the same scene but from a bird’s eye view.]

[We’re] asking, what exactly happens, when moving from sex worker artist representation and representation in artwork of what sex work is, to then shift into looking at sex work as an ethic, for organizing practices, for performance practices, for artistic practices?

Allie: Can you talk a little bit more about this idea of existing in the in-between or borders in the context of the worldmaking that you’ve alluded to? What emerges from being in those in-between spaces and how does that influence your practice?

Wu: I am of the opinion that sex workers always have to be operating in the in-between world because there are so many ways in which the literal job description is itself a paradox to perform desire. I think that living in that in-between world, playing, and operating in it — the process of us making an ethic out of what it means to be a worker — requires us to never necessarily come to a finish. And so the work that we’re going to be doing is always operating in that process as opposed to attempting to create the final product.

What’s been interesting in the process of us writing our manifesto is asking ourselves, “Okay, what’s the vision? What is the world that we’re attempting to build towards? In our utopian landscape, what does that look like?”

The loveliness of sex work is that you get to create these little otherworlds and glimpses into worlds of fantasy that become reality just from the experience of embodying it. But then, also knowing and understanding that some of that exists either extremely far in the future or in a place that cannot exist.

Thea: One of the effects of [being in the in-between] is that sex workers are constantly creating. We are cultivating and indulging in these iterative, fleeting, ephemeral fantasies that can be quite utopic and fantastical, but are also never entirely [ours]. They exist between themselves and a client.

As Wu was saying, the practice is making these small worlds that are like ellipses, that are themselves just cracks that open up opportunities for creation, connection, and imagination. They are not themselves actually naming a future state, and that’s actually quite powerful in and of itself. That’s one of the ways I think that our work situates itself in that gap.

The work that we’ve created is often trying to implicate people in different kinds of relations of power and ethical entanglements with each other. In our work we are curious about what happens in those entanglements as opposed to having a clear political claim about it.

Cleo: I think going back to the question about borders, sex workers historically have often been implicated in ways of making borders, ways of making law, and policing bodies. We saw that happening centuries ago, and we see that happening to this day with facial recognition technology, algorithms that police the flow of the internet.

Our position in those systems of power makes it so that we have to engage with power in ways that are really charged and in ways that implicate our bodies. And I think that is the kind of experience that we want to create as artists, [analyzing] this kind of entanglement.

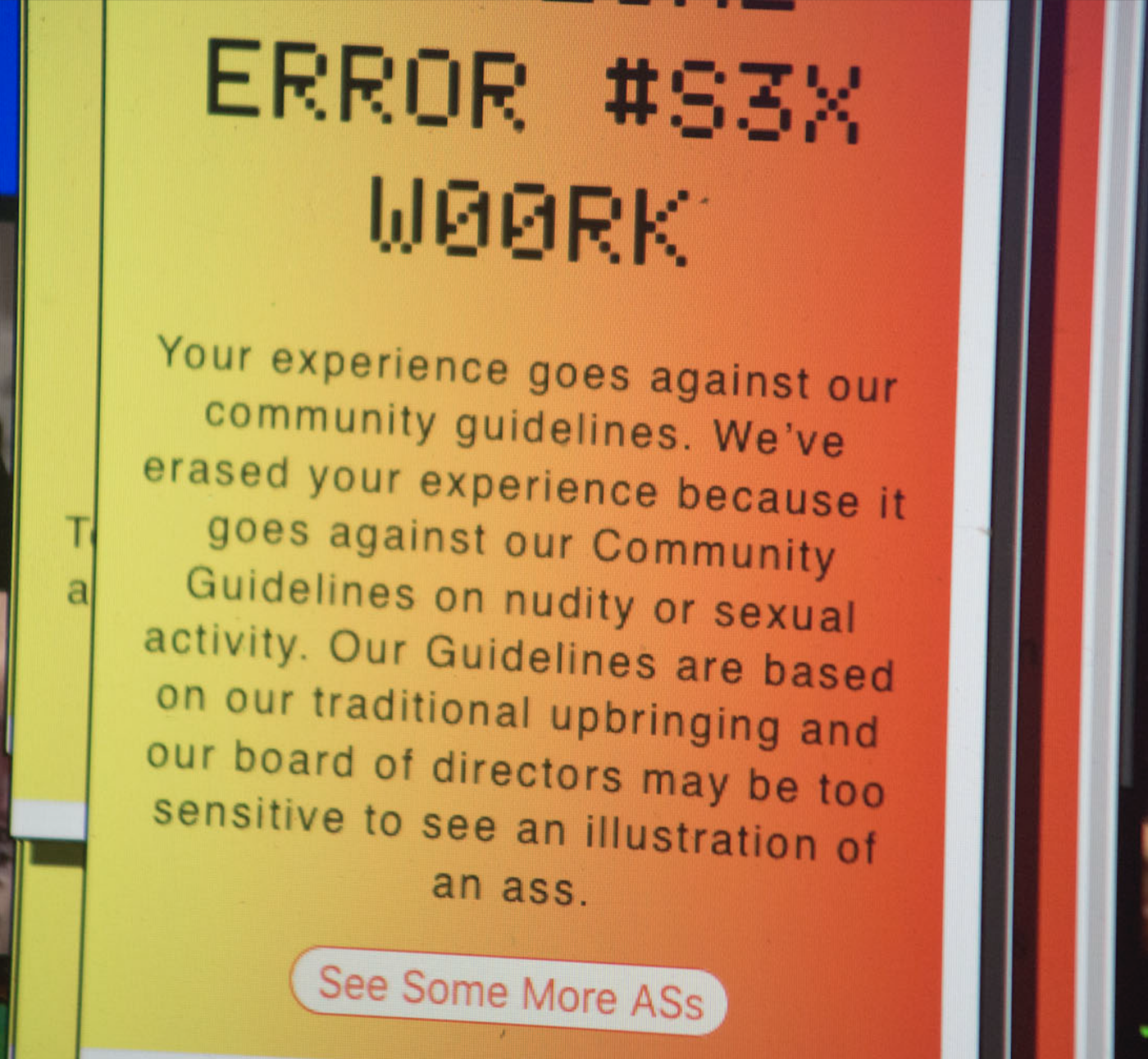

[ID: A screenshot of an error message displayed in the destruction of e-viction. It reads:

ERROR #S3X W00RK

Your experience goes against our community guidelines. We’ve erased your experience because it goes against our community guidelines on nudity or sexual activity. Our guidelines are based on our traditional upbringing, and our board of directors may be too sensitive to see an illustration of an ass.

There is also a button that says, “See some more ass.”]

Allie: Can you share a little bit more about the manifesto that you alluded to, Wu?

Wu: We are attempting to write a manifesto, and I don’t know, perhaps it would be in the spirit of the manifesto if it was never done. (laughter) It’s actually really funny because the three of us have a prenuptial agreement with each other regarding the manifesto.

If anybody decides to bow out of Veil Machine before the completion of the manifesto, there’s a base rate that they have to pay with an additional percentage added on each year to account for inflation. It’s just so sexy of us to do that. (laughter)

In the spirit of this conversation, the thing that I feel is outstanding to me is the process of writing the manifesto, which feels like a love letter to each other. It’s like the world that we’re attempting to build and create with each other. This is the way that we want to speak, not only to each other, but also to other sex workers, clients, and to people who believe that sex work has nothing to do with them.

Thea: Yeah, I agree with you that it actually makes sense that it’s never done. I think that feels really in line with what we’ve been building towards. I’m still curious about what it means to circulate [the manifesto] in the world in different iterations and what it means to share our vision, even as it is evolving.

The process of making it has very much felt like a process of naming what it is that we are to each other, which is itself quite deeply in line with our practice. The work we’ve been making recently explores what it means to turn some of the magic that sex workers give clients towards our sex worker relationships and our intimacy with one another. This [manifesto] — and the time we’ve invested to make it together — has been one of the ways we’ve turned that magic onto ourselves.

Cleo: One of the exercises we did took all of the text from our meeting notes and salons that we’ve hosted, and we collaged poems out of [our writings]. That was the first section of the manifesto. It was a really interesting process for realizing the things that we’ve been working through for years.

The work that we’ve created is often trying to implicate people in different kinds of relations of power and ethical entanglements with each other. In our work we are curious about what happens in those entanglements as opposed to having a clear political claim about it.

Allie: I’d love to zoom out a little bit too, for this issue about labor, we’re thinking through its variety of definitions across art practices. So a starting point for this question is just asking where you locate the labor in your practice?

Wu: When we all first came together we were thinking about the ways in which sex workers are not a monolith and we refused to take a stance. There’s so much plurality in the way that sex workers exist, act, and think. There’s a common saying in pro-sex worker rights circles that “sex work is work.” Veil Machine has a pretty definitive stance against the idea of sex work being work; moreso, [we embrace] the idea that sex work is pro anti-work.

Thea: Yeah, that ethos really animates the way that we think about how we’re talking about sex work in the world. If we want to remain keenly attached to sex work’s radical potentials, the ways in which it transgresses systems of value or borders, it is important to not allow it to get subsumed within this institutionalized and normative myth of what a respectable way of making money might be.

Even within our own internal practices, we think a lot about how money circulates between the three of us and those working with us. We don’t think of it as paying people for their labor so much as it is a part of a mutual aid practice whose ethos goes really deep in the sex work community.

When we were doing E-viction in the midst of the pandemic, the number one priority was putting money in whores’ pockets. Period. That’s not paying people for their labor. That’s redistributing funds to where they need to go. And there is an exchange that happened in that redistribution: other artists helped us with our moderating of the event, our marketing, or they just existed and attended. Decoupling that [practice of] labor for income is one of the ways that we’re practicing anti-work in our behind-the-scenes processes as well.

Wu: There’s something really astounding about the ways in which all of us make money quite differently, that veil coming down and being a personal lesson about how there are different styles of energetic infusions into a client or a relationship. Then, the way that eventually gets released into a gift, transaction, or money being passed into another hand. That is rooted in a sense of abundance that is irrational and sometimes illogical, a kind of fantasy magic that only a sex worker can harness and pull into moments of reality.

Thea: Yeah, I feel like we don’t work with labor. We work with hustling and gifts.

Wu: And the two are very different.

Cleo: And I think there is a parallel there with the work that an artist does, which is really immaterial and intangible. It’s not like an artist is going into a studio to like, labor. There is a kind of magic and transformation that happens of value.

Thea: It’s important that we name that we’re able to come to this kind of critical position because of the work that feminists and art scholars have done to demystify work, for example, arguing art work is work or sex work is work. My own theoretical foundation is rooted in Marxist feminism of the 1970s and the International Wages for Housework Campaign (IWFHC). We are able to think beyond the framework of work because of those who saw labor as a way of getting rights, protection, and respectability.

When we were doing E-viction in the midst of the pandemic, the number one priority was putting money in whores’ pockets. Period. That’s not paying people for their labor. That’s redistributing funds to where they need to go.

Allie: When you think about worker solidarity, in your perspective, what is left out of that conversation? I think it’s kind of building on everything that you were just talking about there within both performance and sex work. Do you find there are any aspects of solidarity or organizing that gets left out above more mainstream conversation?

Thea: I don’t think that Veil Machine necessarily is calling for solidarity in a direct loud way. That’s not our voice; that’s not the kind of worldmaking that we do. But I do think that we are very much so in solidarity with people who are trying to fuck with the system. With people who are trying to survive, who are having to do creative, difficult, unethical things to “make do” in a system that was never designed for them. Be they workers or be they not. What do you guys think?

Wu: In our manifesto, one of the things that we’re attempting to talk about is speaking to people who think that they have no proximity to sex work at all. There is this question [when] looking at sex work and being like, “Oh, this isn’t actually just the issue of, what does it mean to sell pussy for money?”

Thinking about sex work as an ethic is actually thinking about what exactly it is that sex work represents. What are the main themes that can then be extrapolated from sex work, which include issues of labor, class, race, borders? In that way, I think that there’s something in there that Veil Machine speaks to — a plural unity for workers and beyond, but speaking to it in the language of pro-worker solidarity is not necessarily the vocabulary that we would use.

Cleo: Yeah, and I think there are other sex worker organizations who are doing that, like the Stripper Strike in Los Angeles and Red Canary Song. And many many others.

Thea: They are the ones who are making those kinds of claims and we are in full support. We’re often working with them in our personal lives. I just think what we do as Veil Machine approaches these questions from a different angle.

I think why it’s difficult to talk about this and to answer these questions directly is because there is a question of what it means to talk about the work when there is an ethics of refusal at its core. A lot of what we make is about creating opportunities for encounters that can’t necessarily be named, and probably shouldn’t be named.

Because once they get named, then they’re at risk of being subsumed into a discourse that is thoroughly embedded with relations of power. And so playing in that porousness between work and life, operating under a practice of refusal, letting encounters unfold in the moment, and not defining what they’re supposed to be, feels really important to how we’ve been able to create the experiences that we’ve been able to create.

Wu: And scene. (laughter)

EMPRESS WU: [ID: Wu poses in a nightclub with their hand on their hip. She has long black hair and wears an open black leather jacket with ‘x’ pasties on his chest and cat eye glasses. The image is black and white.] THEA LUCE: [ID: A blurry polaroid of Thea removing a brown wig with one hand and holding a pair of glasses in the other. She is wearing a black sweater and standing in front of a large framed portrait.] CLEO OUYANG: [ID: Cleo poses for the camera with a sharp gaze and bold eyeliner. Her dark hair drapes across her face, and she wears a black tank top. ]

Empress Wu

All pronouns

Brooklyn, NY

Empress Wu is the chaos-for-pay alter ego of MJ Tom, a New York City-based cultural activist interested in investigating alternative modes of kinship available via sex work, queer S/M, and digital landscapes. Wu often organizes and performs under their villainous alter ego, Empress Wu. Wu’s work has been featured at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, MoMA PS1, the Performa Biennial, and probably a dungeon near you.

empresswu.net

mjtom.work

Instagram: @thebitchempress_

X: @thebitchempress

Thea Luce

She // Her // Hers

Brooklyn, NY

Thea Luce is the creation of a graduate student and artist based in New York City. Luce’s work examines the intersections of intimacy, labor, law, and ritual in the sex industry. She is a co-founder of the sex-worker artist collective Veil Machine and a frequent collaborator with Kink Out Events. Luce’s work has been funded by Eyebeam and has been featured by Paper Mag, Vice, and Dazed Digital.

Veilmachine.com

Instagram: @veilmachinecollective

Cleo Ouyang

She // Her // Hers

Los Angeles, CA

Cleo Ouyang is a Los Angeles based Dominatrix and co-founder of the art collective, Veil Machine. Ouyang’s practice of BDSM is interested in practices of devotion, sadism, and power exchange. Her alter ego is an artist and performer who works with the artifacts of intimate encounters and rituals of catharsis.

Instagram: @cleoouyang

X: @cleoouyang