“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” –Octavia Butler

4–5 minute experience, or the time it takes to peruse a photo album.

Our landscapes hold memory, at times generative and joyful, and at times painful and violent. Through an interdisciplinary practice spanning writing, photography, and new media, Tia-Simone Gardner excavates geography and geology to locate Blackness in the landscape and unearth the histories embedded in the ground. In the following reflection, Gardner traces the migration patterns of her family and Southern Black lineage to arrive at a deeper understanding of home.

BY TIA-SIMONE GARDNER

—

Octavia Butler,

Parable of the Sower

When was the last time you went home?

I currently live in Saint Paul, Minnesota, but it is hard to think of the city, or really anywhere outside of the places my mother and grandmother lived, as home. Home is a thousand miles, a two-and-a-half-hour flight, or a seventeen-hour drive south and east. Home is a different spatial reality. Home is a different belonging. Home is an altogether other Black landscape.

I grew up in Fairfield, Alabama. It is my home and it is a place where my practice as an artist begins. For most, it is not a place they know, or, know as intimately as its neighbor Birmingham. I have known Fairfield my whole life, as did my mother. I knew this place so intimately that I didn’t realize some of the very obvious ways it had been planned — as a city, as a place, as a landscape.

Fairfield, Alabama, as I know it, was incorporated in 1919, making it just over one hundred years old when the city declared bankruptcy in 2020. A hundred year city. A two-generation city. In relation to Fairfield, I realized that a place that had seemed so permanent, that had given my identity as a Black-Southerner such fixity, was in fact temporary. The visualization of Southern Black life that is so often materialized alongside crop capitalism — cotton, indigo, rice, tobacco, sugar — is not necessarily where this place begins. The geologic life of this place, the close proximity of iron ore, coal, and limestone, gave it birth.

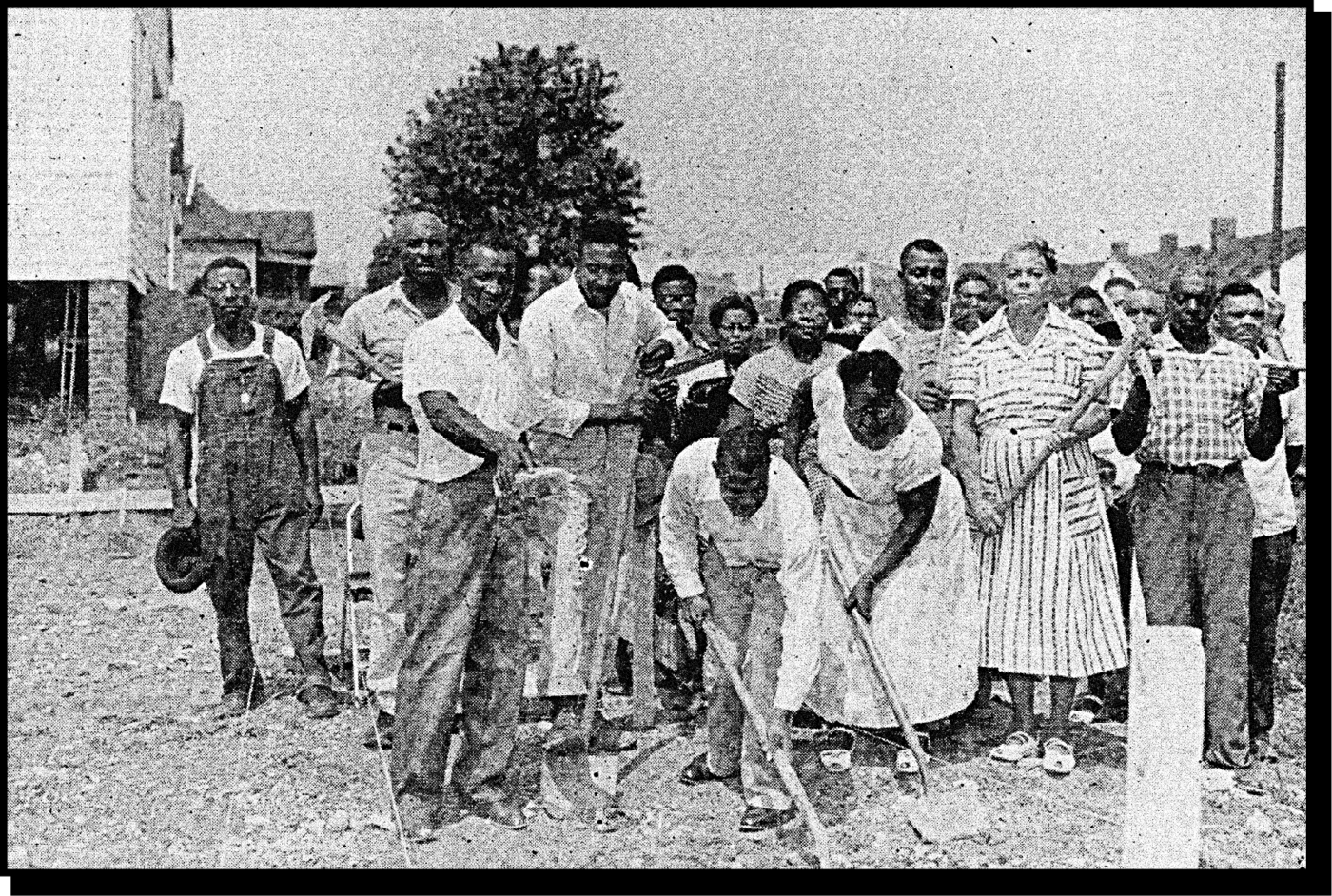

[ID: An old black and white photograph, pixelated as if copied from a newspaper. A group of twenty or so Black people of various ages face the camera, framed with a building and a single tree behind them. Many are holding shovels and other tools. A woman and a man in the front row are bent over, their shovels wedged into the ground. One woman poses with a pick axe.]

I am interested in this temporary territory. The short life it has had, the ways that it has been physically transformed, have left deep and dramatic scars in the landscape. The place that I am from is a meticulously planned city, but to navigate it feels like you are following a massive design mistake. Fairfield was and is a model-city for US Steel Corporation. There is, in fact, a US Steel headquarters that is a familiar fixture on one of the hilltops, up the street from my grandparents’ church. Street after street dead-ends into short and tall evergreens, disguising a form of container. A planned container. A color-line. A model-city that modeled a form of spatial segregation, concealed by inconspicuous hedges and forests. As a child, I noticed the trees, and their accompanying dead-ends, but didn’t think about the intention behind them. As an adult, I wonder how growing up in this sort of complex of ecological apartheid shaped my relationship to trees, my sense of “green space.”

I suppose Fairfield is a green space, but I want to claim it also as a Black place, not separate from a very literal form of environmental racism but also not wholly defined by it either.

[ID: An overhead photograph. A row of trees runs down the center of the photograph, bisecting the image into two sections. On the right is a residential home set alongside a small road and electrical wires running parallel to the trees. Around the house is a green lawn with an array of garden beds, dormant for the season. The gardens take up almost as much ground area as the house itself. To the left of the row of trees lies an access road and a stark, gray industrial plane with deep, diagonal grooves cut into it.]

I suppose Fairfield is a green space, but I want to claim it also as a Black place, not separate from a very literal form of environmental racism but also not wholly defined by it either. I think about my always changing relationship to this always changing place and am thankful for how it has pushed me to think about Black Southern identities as dynamic rather than static. Something I have always understood is that our grandparents were Southerners. I understood that I had cousins, aunties, and uncles who lived in places like New York, Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles, but I understood also that my grandparents had remained in the South. I knew they had come to Fairfield from Mississippi but my understanding about the South, our South, was that the Black landscape somehow always remained in place. I believed they were in place, and that they had always been in place. What I realize now is that they made place. All of my elders were from elsewhere and they collectively produced this town, a composition of Black landscapes, from Meridian to Philadelphia, Mississippi, from Warm Springs, Georgia and Indian Springs, Alabama. I grew up in a town of migrants, changelings. They didn’t go north to the ready-made places that welcomed other parts of my family; they made something else.

They made place from change, and perhaps that idea is rooted deeper than those trees.

[ID: Tia, a short Black woman with braids and glasses, looks suspiciously at the camera.]

Tia-Simone Gardner

She // Her // Hers

Saint Paul, MN

Tia-Simone Gardner is an interdisciplinary artist, educator, and Black feminist scholar. Working primarily with video, digital drawing, images, archives, and spaces, Gardner has made a practice of tracing Blackness in landscapes, above and below the ground’s surface. Through her work with still and moving images, she brings together fragments of things and lives alongside the events and the places to which they gave meaning. Ritual, disobedience, geography, and geology are the specters and recurring themes that cross her work. Gardner grew up in Fairfield, Alabama, across the street from Birmingham, and learned to see landscape, capitalist extraction, and containment through this place. She received her BA in Art and Art History from the University of Alabama in Birmingham. In 2009 she received her MFA in Interdisciplinary Practices and Time-Based Media from the University of Pennsylvania, followed by her participation as a Studio Fellow in the Whitney Independent Study Program. Gardner has been an invited artist at a number of national and international artist residencies and been awarded a number of fellowships. Her current work brings the questions of Black geography to questions of geology in order to examine ideas of race and landscape along the Mississippi River and her home in Fairfield/Birmingham, Alabama.