“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” –Octavia Butler

“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” –Octavia Butler

8–10 minute read, or the time it takes for a midday stretch.

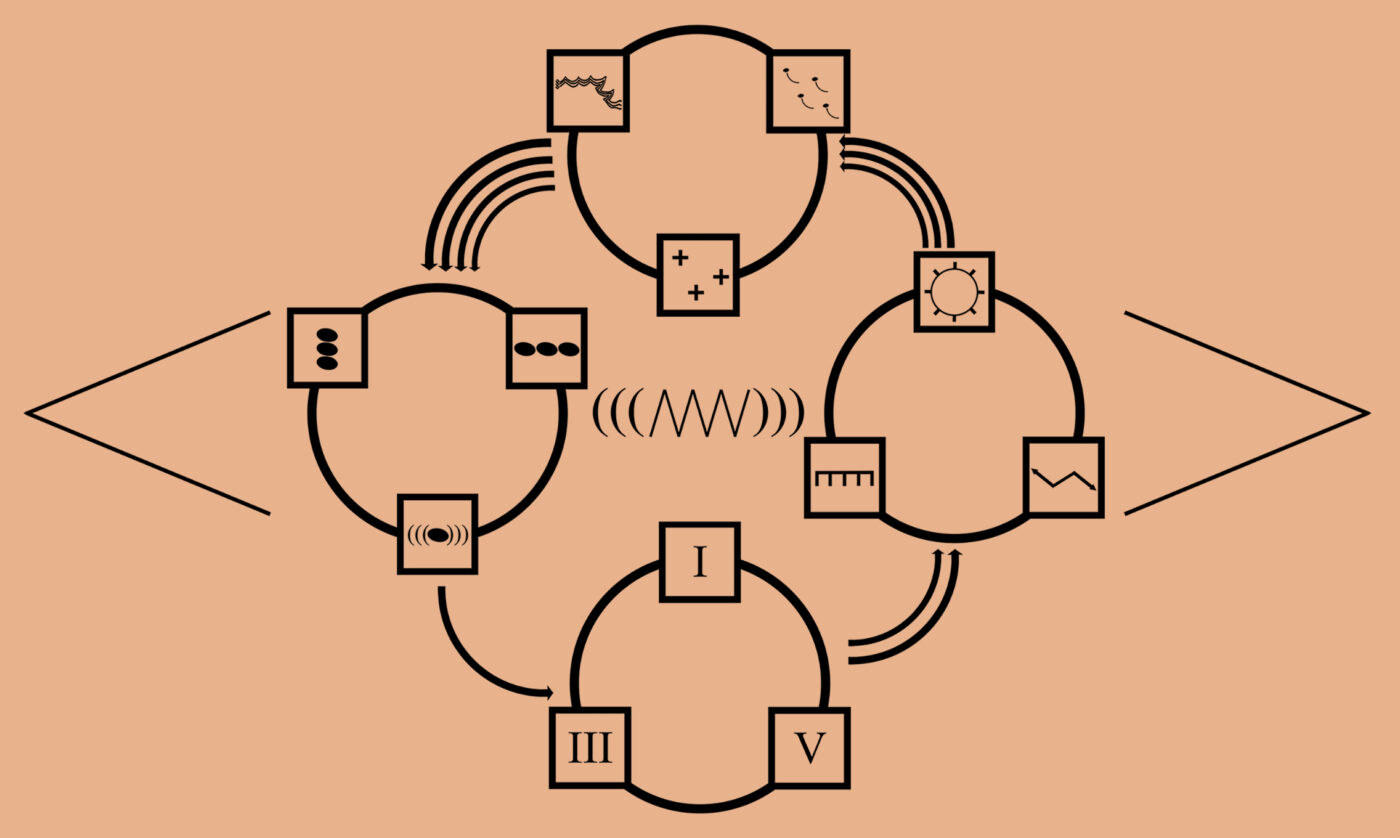

Music scores can be coded as instructions, but Raven Chacon prefers to craft them as invitations. His notational style often directs the performer to take cues from their immediate surroundings to inform the composition’s shape and sound, and this latest one is no exception. Here, Zoë Wallace, a musician and USA Development Coordinator, talks to Raven about the development of “Compass,” a solo for electric guitar, and performs two complementary versions of it.

Instructions to Compass:

Performed by Zoë Wallace in September 2021.

This score, Compass (2021) by Raven Chacon was commissioned by United States Artists for New Suns: Listening with Artists, and performed by Zoë Wallace to deepen the exchange and conversation between Raven Chacon and this specific piece.

I like to use all of those simple iconographies because I think they have dual or triple meanings.

Zoë Wallace: The title “Compass” seemed fitting to me, but I was curious about your own reasoning behind the name. Does it come from the graphic score resembling a compass, is it from using nature as a compass of sorts to point the performer into their next action, or is it a combination of those things?

Raven Chacon: Yeah, that’s right. You may have described it better than me. The reason for doing it outside was to locate the performer in a place where they would be conscious of their surroundings and the four directions, so they could use them as information for the piece. Let’s say they just appeared in some random location to perform the piece. Even though they might not know where they are, they would be able to gather information from the shadows to know what direction they’re facing. I was also interested in the other information that might give them an indication about where they are located — the wind maybe does that, maybe the animals are telling something about where this person is — and even more importantly, maybe all of this information is also telling this person about how they are encroaching on the space or how their presence is influencing this place that they are sitting at. At the same time, there is this circular motion within the score. I didn’t start out intending for it to look like a compass, it just so happened that I was using this number of four in the parameters I was working with and it ended up being this circular shape in the notation.

Zoë: That’s always amazing when things come together in that way! Speaking of the circular shape in your notation, I know using symbols in scores isn’t anything new to you. Where do you get the ideas for your graphic scores?

Raven: A big influence is still Western classical notation as it has evolved through the 21st century. Symbols such as a left-hand pizzicato on the violin, which resemble a cross, would be something that I might transfer over to the guitar. At the same time, however, a cross has other kinds of symbology: it could mean the stars, or it could mean the four directions, like a compass. I like to use all of those simple iconographies because I think they have dual or triple meanings. A lot of them are expressive, but I still try to be very intentional in what I’m designing for these so they aren’t free improvisations. They still have detailed instructions of how they’re executed, but for me they serve better than something that might be more precisely rhythmically notated or pitch notated. Those two parameters are less important to me than something like timbre, or gesture, or even the location of where the performer is.

For example, the volume in this particular piece is really important, and so my goal was to find graphics that notated that. And then obviously things like arrows have a purpose of saying how you navigate through the piece. It could be interpreted as improvisation, but I don’t think it is in this case. It’s guided by other forces and in collaboration with those other forces to find the way to navigate through the piece.

Zoë: There’s also a certain freedom in notating that way, and I think the end results are often a piece that captures the sound world a little differently every time it’s performed. You’ve talked about this a little bit already, but how do you think this really influences the sound world in which you create? Is it different every time it’s performed with only the timbre intact, like you described?

Raven: I try to make these scores still sound like they have an intentional form and intentional timbre and intentional context, you know? So I don’t think there are drastic differences in performances as far as the form or the timbre would go, even with some of my other pieces that don’t say what instrument should be played. Even in those cases, I think they still end up very similar in some way and fulfill the intention that I was hoping for with the piece.

“Compass,” 2021. Composition by Raven Chacon. Commissioned by United States Artists. Performed by Zoë Wallace in September 2021.

I’m interested in the unexpected surprises and the accidents that emerge when you put your trust in musicians. Those are the things that can never be notated.

Zoë: It’s cool how notation that is not necessarily standardized in a traditional way can still get consistent sound and effects across. I think this is a testament to how articulate you are in the way that you notate and explain everything. It’s very clear what’s supposed to happen and how the sound is supposed to come across. Even with that being said, there’s still a large amount of agency and trust that you put in the performer to be able to interpret it and bring out this sound world that you’ve envisioned. Do you think that this way of writing notation enforces that kind of trust between performer and composer?

Raven: I do, I’m always interested in furthering that relationship. I think the reason I do this is because I value the collaboration between musicians, and I don’t find that traditional specified notation always allows for that kind of reciprocal relationship, or trust as you put it. I’m interested in the unexpected surprises and the accidents that emerge when you put your trust in musicians. Those are the things that can never be notated. Those are the things that make the piece different every time, but still the same idea and essence. And for me, the music has to be fluid enough to do that for every performance. I still hesitate to use the word improvisation because I think that implies some other kind of freedom that I’m not necessarily looking for. I’m looking for this system that a musician and I will share in an experience, so we can learn together what the piece is telling us.

Zoë: Right, a certain mutual understanding that both partners are needed to bring this piece into the world. Changing subjects slightly, after receiving the score one of the first things I noticed is the instructions regarding performing the piece outside and trusting in the area around you to create the direction you go to next. Performing outdoors, or in a specified location at least, seems to be something recurring in your work.

Raven: It’s not always something that’s there, but since the beginning of my career in composing music and making so-called sound art, I’ve worked with things like field recordings and then, later on, site-specific installations that respond to the history of a place. Early on in my education, I took a recording class and there was a lot of emphasis on how the room should sound and how you should try to get the room into this neutral state. After a while, I just started thinking, “Well, how about we just do it outside!” Sure, you’re going to pick up the wind, or an airplane, or a car driving on some distant dirt road. But maybe that’s part of the piece, maybe it’s going to create a nice sound that’s better than the air conditioning going off in a recording studio. So I started working outside for some of these and taking into consideration what it was like to play music in that space instead. There are all of these other elements present, like the animals or wind, and all of that ends up in a lot of the work, too.

Zoë: I actually had considered going and recording the piece outside, and I was a little worried about picking up some of the extraneous sound in the recording. Maybe I’ll go give it a shot after all!

Raven: Two versions would be cool! I really liked the studio version you made, and it’d be interesting to see it compared against a video of you performing it outside.

Zoë: Yeah, definitely! It’s kind of funny that you mentioned the wind because the fan and the breezes coming in through the open window were both influences on my direction in the piece when I was just recording in the studio. Even the direction of the fan and it’s shadow on the wall had influences, and I didn’t start off with that in mind. Since I was recording indoors I didn’t think as much about the influences of nature, but it ended up happening completely unintentionally.

Raven: Wow, that’s funny! Unintentional, but obviously it’s going to be there and it peeked out at you, reminding you even in your iteration that it was still there. Maybe it’s something we can’t escape, you know. Maybe it’s going to manifest in other ways every time, even when we’re not looking for it.

[ID: Raven looks into the distance beyond the camera. He has long dark hair and wears a plaid shirt.]

Raven Chacon

He // Him // His

Albuquerque, NM

Raven Chacon is a composer, performer, and installation artist based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. As a solo artist, collaborator, or with Postcommodity, Chacon has exhibited or performed at Whitney Biennial, documenta 14, REDCAT, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Borealis Festival, San Francisco Electronic Music Festival, Ende Tymes Festival, 18th Biennale of Sydney, and The Kennedy Center. He is the recipient of the United States Artists fellowship in Music, The Creative Capital award in Visual Arts, The Native Arts and Cultures Foundation artist fellowship, the American Academy’s Berlin Prize for Music Composition, and in 2022 will serve as the Pew Fellow-in-Residence.