“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” –Octavia Butler

45-50 minute experience, or the time it takes to read a chapter or two in your favorite book.

A CONVERSATION WITH

JULIANA ROWEN BARTON AND ANGELA WASHKO

Angela Washko, a media artist, and Juliana Rowen Barton, a curator and researcher, engage in a conversation centering motherhood and the myriad ways labor and life swim together. As one of the curators of the project Designing Motherhood, Juliana brings a rich perspective on the history of caregiving and art. Angela is in the midst of work on a new video game inspired by her own experience becoming a mother at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The two talk about evolving one’s creative life to make room for childcare, and the tradition of mothers documenting and making sense of their experiences through art.

Kate Blair: To start, I would just love to hear you both talk about the exhibition you worked on together. I’m curious, Juliana, what the genesis of this exhibition was, what your concerns were in putting it together, and how you worked with Angela?

Juliana Rowen Barton: At Play, which was on view November 2022 to April 2023 at Gallery 360 in Boston, was the exhibition. I’d been thinking about play for a long time. Actually, when I was an intern at MoMA, the curators I was working with were developing the Century of the Child exhibition; thinking about childhood and design and play was obviously a big part of that. So thinking about toys and objects in that area. And my research, as we’ll talk about, has circled around elements of motherhood, which is very interrelated. I’d been noticing some work by artists that I had been speaking with, that play had been a part of their practice in some way, not coincidentally, a few artists involved in Designing Motherhood. And I thought, there’s an exhibition here somewhere, and I was really excited for it to come together. I think as you’ve pointed out or identified, it has some really gendered elements to it.

I did focus on female-identifying artists, and all of them, not coincidentally, are parents. I didn’t aim for that to be the goal, but I think that that’s an important element I always talked about. I came upon Angela’s work as I was doing some research into artists, particularly looking at the digital elements of play and video games. I work at a university where there’s a really strong game design program, and I always aim for the exhibitions I work on to engage with the curriculum. And no surprise, Angela’s work really spoke to a lot of the students, not that they had necessarily played the games that you played, because we unfortunately are much older than them, so they look a little bit retro to the students. But really it was fascinating to watch them analyze the retro elements and identify which part of the games that they are more familiar with.

It was really great to have Angela’s work represent at least part of childhood that resonated with me in some way. I’m not a gamer, but I understand that element of it, being, I think most of us were from the same generation of people, but for it to be really diverse. Angela’s work was in a part of the gallery with Ellie Richards’ sculptures, which are these assemblages or ready-mades of toys and tools put together alongside. And then there were AI-generated toys, artists turning stuffed animals inside out, and chroming a dollhouse. There was all this different stuff, and it was really great to have Angela’s work represented alongside all of that.

[ID: A television displaying a video featuring an image from a video game is mounted on a wall collaged with blue-tinted videogame stills. An adjacent wall displays three framed cyanotypes with similar game imagery.]

Angela Washko: My work in the show was a video installation surrounding a video called Don’t Leave Me, and it was part of a larger body of work I started making called Heroines with Baggage, which was really the first series of work I made where I had decided that video games — which had been such an important part of my life, but I had not seen widely represented in the art context I was aspiring to be in — where I was like, I’m going to replay all of the games that were formative to me and look at the ways in which the perspective or point of view, or lacking point of view of women in these games impacted my own identity formation. I began to replay all role-playing games — so very long, eighty-hour games — recording all of the moments where women were speaking or being the center focus, and started looking at the patterns that evolved in their representation. I knew there were things in there that intuitively bothered me or intuitively left me feeling like there was a very one-dimensional look at who women were if we just looked at these games.

The project was called Don’t Leave Me because there were so many of these games where even playable female-identified characters were constantly dependent on a male protagonist and constantly uttering the phrase, “don’t leave me” in this extremely desperate, stereotypically needy way. And I started to realize as I was looking at this, that these games I had loved so much, really I was not the audience for, I was not the one who was being marketed to through these games.

I really appreciated the framework of the At Play exhibition because [Don’t Leave Me] is often shown in art and video game survey shows; it’s often shown in feminist digital art framework shows, but I don’t think it had ever been shown in an exhibition that focused on childhood development in play. That’s really in the original writing about that work, which I will say was rough and extremely personal. It came from a personal investigation of trying to figure out why my own perspective on courtship and relationships was the way it was, particularly with cisgender men, and the relationship that storytelling, role-playing video games had to that. For me, there was a real deep connection to an analysis of the way that storytelling video games impact childhood development, ideology, and identity. I was super appreciative to have this particular work in that framework.

Also, at the point that we started talking, the work had just turned ten years old. I got to look at expanding the world of the work a little bit. I had identified all these tropes that I’d talk about when I’d give talks about the work, but I’d never gotten a chance to display the analysis aside from this, I would say, fairly devastating film. So I got to do a little bit more of that visualizing, the process of analyzing this media, through this new installation.

[ID: Visitors view artwork on display in the At Play exhibition, including Angela Washko’s cyanotypes. Toward the back of the space, a number of tools are hung on the wall, wrapped in various kinds of colorful children’s toys.]

We might take for granted the ways in which the things we played with impacted how we interact in the world, and the ways that so much of that play can be feminized or gendered.

Juliana: I really loved the installation. It had three parts to it, the Don’t Leave Me video, which is chilling, the cyanotypes (a lot of people asked about translating a video game to cyanotype, that moving image to still image process), and then you created this wallpaper that was similarly blue and had images, more stills. So even if you didn’t sit and watch the video, you were confronted with the repeated pattern, both in a repeated pattern of a wallpaper, with the language of “don’t leave me, I need help,” damsel in distress. That language is put right in front, whether or not you chose to sit and watch. I think the video was seven to twelve minutes long. You couldn’t really look away from that. I thought the three elements of that really played well together. And the wallpaper was new, right? That was the new part of the work.

Angela: That was new, yeah. That was just for y’all!

Juliana: I’d love to hear about the cyanotypes because that was the first thing I saw and was really struck by.

Angela: Even before I made the videos, I had been making prints from the series, identifying these still moments that I thought encapsulated these recurring themes I was finding in the games. I’ve always appreciated cyanotypes and their relationship to the history of documenting organic materials.

Especially at the time that I was making the work, video games were not a hugely represented or legitimate topic for art historians. The first time I showed this work at an art history-centric conference, some of the feedback I got included, “Oh, you seem really smart, but why are you wasting all your time in these games that only ten-year-old boys are playing? I think there are better uses of your time.” And this was at major conferences, so at the time, it was not taken seriously. I felt like lending this going-obsolete digital gaming technology to something that has been used to preserve organic materials for a long time was a way to create a time capsule for this thing.

Like you said, there are gamer kids now who are definitely not going to know a lot of the references in that work. Same for the audiences that typically attend art gallery shows. There was an almost tactical impulse for me to say that what was happening in that moment was incredibly important, and we have to preserve it and look at it, because this is the foundation that games have been built from.

My prediction was that games were only going to become more and more a part of everyday life, especially as things were becoming more immersive, more multi-user and network-oriented, and more connected to the broader entertainment industry. Also, I really missed making tangible physical objects, and it got me into hand-painting.

Juliana: It’s really interesting to me that you say that part of the cyanotype, or some element of it, is legitimizing or making someone take it seriously, because I feel like that’s part of the mission with the show of At Play too. We might take for granted the ways in which the things we played with impacted how we interact in the world, and the ways that so much of that play can be feminized or gendered. No one’s telling Jeff Koons that his giant metallic balloon toys are not legitimate, or Duchamp and his chess boards; play has been a part of art history or the creation of art for a really long time. But of course, when taken in a gendered context, we need to be reminded for us to take it seriously.

[ID: Two computer monitors are set up in front of three columns, showing colorful paintings and hand-drawn stills from the Mother, Player game.]

Kate: I feel like that’s a good transition point to the next section about motherhood and labor. Angela, I know you’re working on a new game that has to do with motherhood during the pandemic and you’re hand-drawing a lot of the content in that. I’m curious to hear about that game, but also curious about that labor factor or just the nature of that more tactical work that you were just talking about, with the cyanotypes and how you enjoy working in that.

Angela: Oh, I did enjoy working on thousands and thousands of hand-drawn frames of rotoscoped animation…(laughter) I started thinking about the idea for Mother Player while I was late in my pregnancy with my daughter Yvette, and I was searching for the perfect books to read that would really speak to me and my experience. There were not many. There was so much writing about pregnancy and early parenthood and early childhood that just felt very gendered. Very goddess-y.

But I found a revelation: I was given this book, Mother Reader, edited by Moyra Davey. It featured short essays across a long span of time from artists and writers who talked frankly about both the incredible things about parenting as a creative person, but also the real struggles that artists and writers have always been having around carving out space for themselves and their work, while also having this huge transformation and creating care structures around their kids and a lot of different approaches, and even some resentment.

In my interpersonal life in the pandemic, I definitely had to, in a remote way, reconnect with all the artists that I knew who’d had kids, and I started to get some of those stories that way as well. There were things I experienced in the maternal healthcare industry that were harrowing, things that happened to my body that were harrowing, and it wasn’t until [the Mother Reader book] that I found something that really spoke to my experience, and also this upcoming potential shift I would have to make in the way that I work and live.

After I had my daughter, I started to realize how differently I was going to have to structure the way that I make as an artist. My projects are both research-intensive and labor-intensive. Before, as someone who’s an artist and educator, I would have whole summers and professional leaves or breaks to be able to really deep dive, many days in a row of just working through projects. And then I was in the pandemic with no childcare, no access to my community physically, a newborn, and horrible issues around breastfeeding and breastfeeding politics.

My new full-time job was feeding my kiddo, and then I started to realize that the only time I was going to be able to work would be when she was napping. I was finishing up a feature film, looking at cuts and working with editors during this nap time and in the middle of the night and during feedings. And eventually I was like, this is the subject of the work. I was like, how can I fold this experience that I’m having and this new world that I’m building with my daughter and partner into my work?

And then I started thinking about how meaningful Mother Reader was to me and wanting to make a video game parallel work. There is no video game that currently exists that really goes into the politics of parenting — certainly not artists or creative people considering parenting or gestation. Very few games even incorporate mother figures at all. And the trope of the Dead Mom is really unfortunate; I’ll certainly someday make another project about that.

I felt like this was something that I could contribute to the landscape of both games and the art context that felt missing for me. So I started working on this game while Yvette was napping, and I was just making these short, looping vignette animations. I would take a video, then I would break it into still images, then I would translate those still images into frames of drawing, and then I would animate them all. I eventually started writing this first-person story of my experience deciding to have a kid and finding out I was pregnant the same day that I found out everything was shutting down for the COVID-19 pandemic — getting the [pregnancy] test result while reading an email from my boss saying, “we’re going to be teaching remotely from now until…?” and going through the process of thinking through how that’s going to change my life as an artist, and also navigating what that meant for the maternal healthcare industry as well.

I’m carving out a creative practice moving forward that ultimately includes my family rather than sets them as this separate thing. As she got older (and I was of course still working on this project because that’s how it goes), my daughter developed a real love of painting. All of the backdrops of the game are hand-painted by Yvette. She makes tons of paintings I scan. We have 600 of them that are assets in the game. I’ll make these little animated icons, and she’ll respond to them, and I’ll record her responses. And then it’s kind of an Easter egg in the game, but you can click through them and hear her say [makes baby noises], or “I like that!” My partner made the soundtrack for the game using all of Yvette’s really annoying-sounding toys and manipulated them into a fairly beautiful soundscape despite their cringey origins. It’s about to be finished, and there’s going to be an installation version exhibited at Public Works Administration, a gallery in the New York subway, coming up.

[ID: Photographs from the Designing Motherhood exhibition displayed in a gallery on the wall. In a triptych, a pregnant woman holds various seated poses. A gallery of black-and-white photos document marches and protests alongside various other intimate moments.]

How can I fold this experience that I’m having and this new world that I’m building with my daughter and partner into my work?

Juliana: I’m so excited to see that come to life. There are women who have historically taken up the subject of motherhood. You think about Mary Kelly and Alice Neel. But one of the things that I realized in Designing Motherhood is that we have included a lot of contemporary artists, who are, I’d say, at later stages of their career, who didn’t take up the subject of motherhood until they were much more established.

The ur-example for this is Deborah Willis, a renowned photographer who has this incredible self-portrait print called I Made Space for a Good Man. It was a self-portrait she took while she was pregnant, and she was told by a professor in graduate school when she was in art school getting her MFA, that she was taking up space for a man in the program.

It was only later in life that she found the negatives of the photos. And her son, who she was pregnant with [when the photo was taken], encouraged her to take a closer look at this. And she found a subversive and more empowering way to approach that, which was like, she has had an amazing career. She was not “taking up” space for a good man. In fact, she was making space for a good man — the child that she was bearing, Hank Willis Thomas, is an artist in his own right. But that work wasn’t made until 2009, and she’d had a really long career before that.

Angela: The Designing Motherhood book was so important to me, and I’m so thankful for it.

Juliana: You were talking about the things that didn’t exist when you were pregnant, and that book wasn’t available yet!

Angela: Yes, that came out in September 2021. I think we got it a year after Yvette was born. As soon as it was available, I was like, yeah!

Juliana: It’s been such an incredible project to work on and to think about. I’m not a parent, or I don’t have a child myself. There are a lot of children in my life in various ways, but I am a member of the five-person curatorial team. I wrote for the book, and I worked very intensely on the book. The project was founded by Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick, but it’s been such a wonderful collaboration since I joined in January 2020. Labor of love is the only way to describe it, which I think sounds really similar to your project, Angela. Labor of love. It’s a really natural progression from some of my own research interests, but also a way for research and politics and my moral beliefs to come together, thinking about artists as humans and the labor behind the work that they do, both within their work and outside of it. Curators as humans…cultural workers! I don’t think it’s insignificant that so many museums and cultural workers have unionized and their labor is being recognized in different ways during the pandemic. Charting that is also a subject that feels related to Designing Motherhood to me as well.

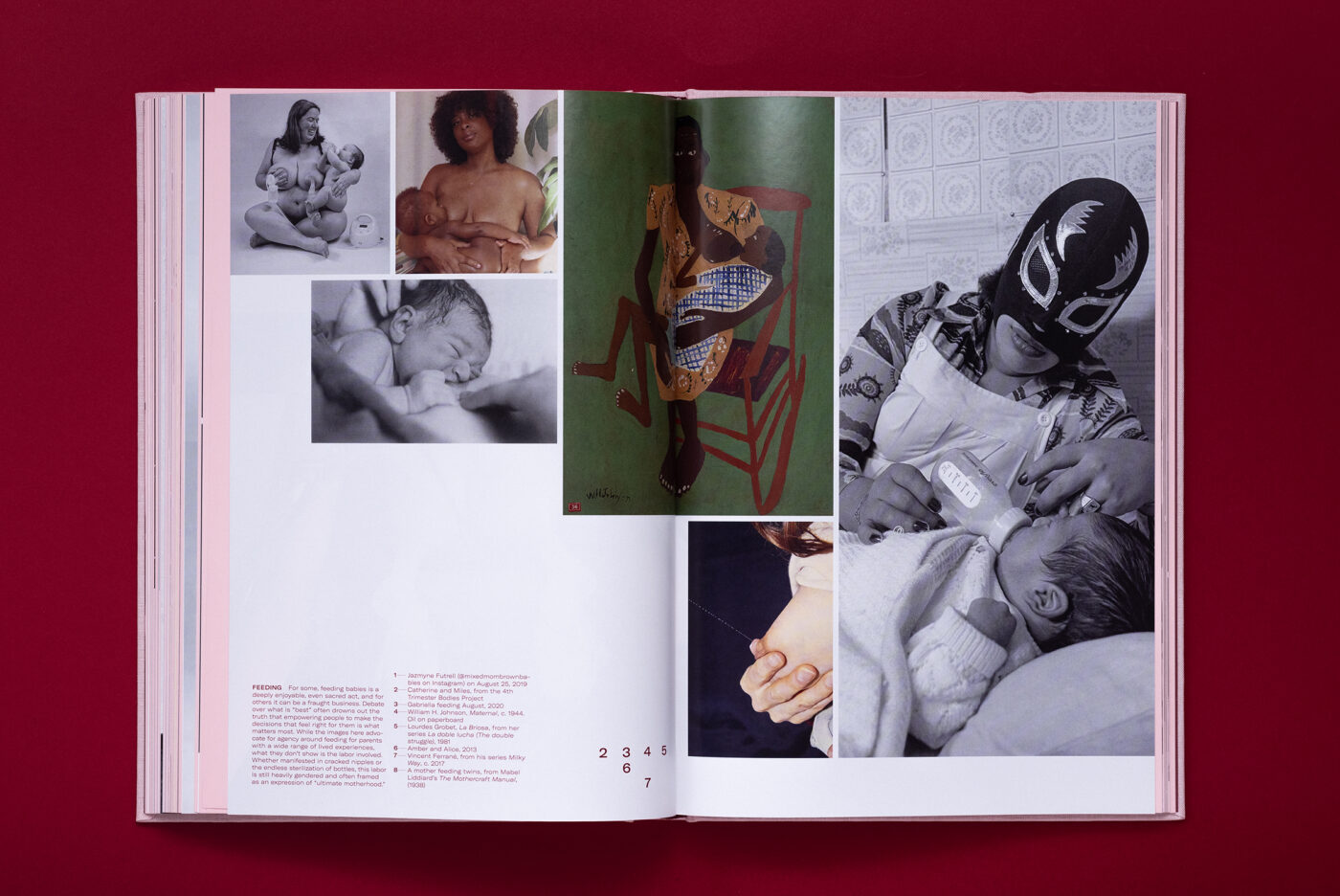

[ID: A spread from an open book shows a number of photographs of babies breastfeeding. On the right, a woman wearing a luchador mask feeds a baby with a bottle.]

I hope that in some way that the work itself embodies that process and that the care and the labor around the drawings in some way speaks to what it felt like to have to make within these new conditions that I was in.

Angela: Oh yeah, I forgot the labor part of that question. What a great segue. (laughter)

I think something that was really important to me, a lot of men (especially men without kids that I’ve talked to about this project, or men in the art tech space), when they realize how many frames of drawing have been hand-drawn for this project, they’re like, why don’t you just train a machine-learning model on your drawing and you’ll be able to generate the drawings faster? And yeah, I use those models for other things, but I’m hoping that the labor is truly felt in the work, and that because of the way that my making process shifted as a result of parenthood, this [feeling of] I have forty-five minutes, I can make maybe draw a frame or two in this time. And after the nap is over, care again, then nap happens again, okay, back to the drawing.

I hope that in some way that the work itself embodies that process and that the care and the labor around the drawings in some way speaks to what it felt like to have to make within these new conditions that I was in. To automate that, while efficient, and I’m sure there are interesting artifacts that would come out of that, it feels counter to the politics and hopefully intention behind the work.

Juliana: It reminds me of someone else included in At Play and whose work has been in Designing Motherhood, Ani Liu, her series — oh, it’s called Labor of Love, of course it is! She has this series on pumping and feeding that has a couple of manifestations. Ani gave birth to her second child in September of 2021 and went back to work within a couple of weeks because she had just started a teaching position that didn’t afford her maternity leave. She hadn’t been an employee long enough to receive maternity leave.

So she went back to work and had a really intimate relationship with her breast pump as a result, and a lot of the apps around feeding and changing track a lot of data, and Ani’s data-interested, so she turned that data into a visualization. It has a physical form and also a visual chart that shows, in the first thirty days, the number color-coded to the times that she was pumping or changing. And I feel like there’s a real parallel to what you were showing — those little slots of time that you were working in. Show one of those men who doesn’t have children this map and that kind of visualization and see how they respond. It feels like it’s in conversation in some way.

Angela: I initially hated the idea of using those apps, but it was only through them that I was able to realize just how much of my day was spent feeding, especially because I was given actually very, very bad advice and instructions by a breastfeeding consultant who was actually having me feeding and then pumping immediately after feeding. I was stuck in this cycle of over forty hours a week of pumping and feeding and completely tied to this machine.

I needed for myself to see that as data in order to eventually make the decision that this isn’t working for me, and it seems wrong, and to ultimately make arguments to advocate for myself. I think without that data, I just would’ve been like, well, this is just my life now.

Juliana: That time is valuable. When Ani’s work was in Designing Motherhood, it was at a moment of time when formula was very scarce and very expensive, and quite frankly, a Republican response to that crisis was like, well, breastfeeding is free. And it’s like, no, it’s not. It’s absolutely not free. Take a look at a chart of how much time a breastfeeding person spends in the first 30–60–90 days and how little else can be done during that time, and tie that into maternity or parental leave statistics, and it just gets depressing very quickly. But that is not free time!

Angela: No.

Juliana: That is time you are laboring.

Angela: Yes.

[Video description: An animated trailer for a video game with soft ambient music playing in the background. The video switches between hand drawn graphite animations of mundane glimpses into every day live of the artist during the COVID-19 lockdown and black transition slides narrating the video games user’s point of view in green text.]

Kate: I’m curious about the experience of playing this game that you’re working on, Angela, and how that lines up with all of these moments of time. Are you hoping that people will experience that embodied feeling of the time that it actually takes to be a mother or be a caregiver in this way? What are you anticipating the gameplay experience is going to be like?

Angela: The framework that I’ve been using for the last couple of game-based projects that I’ve made, I describe it as “tactical embodiment.” Part of it is a resistance to the way that people want to project empathy onto story games and the discourse claiming if we make a game about this horrible thing happening over here, we will change it, or it’ll be better, or we’ll be a part of a movement to fix it. I’d like to distance myself from some of that, but I do think that the way that storytelling games can orient a viewer to a particular point of view or way of being and thinking, is an incredibly powerful part of the medium.

So in Mother Player, I am hoping that players who have not had parenting experiences, but who are artists, will be able to think through and feel through the way that parenthood and care for those who do parent impacts their creative practices.

The ultimately very positive and hopefully interesting way of expanding one’s idea of what an artistic practice looks like, is very inspired by an artist in my life: Alicia Wormsley. She’s an incredible artist based here in Pittsburgh, and [I appreciated] getting to see the way that her child Shepherd is a part of her creative worlds, but always with agency. There’s always a very thoughtful conversation between the two of them about what it means for them to participate in her work. There’s always a conversation about when or if something needs to be removed or come down or eventually not be shown.

There’s another artist in my life, Lenka Clayton, who created the Artist Residency in Motherhood who I think similarly was like, parenting has transformed my ability to make work, so instead of thinking about that as a deficit or a failure, or that I can’t be an artist anymore, let’s think about the framework of parenting as an interesting space to work within, or an interesting set of parameters for producing conceptual artworks.

I think I have absorbed a lot of tropes about what it takes to be an artist. I think [the game Mother, Player is] working through some internalized ideas or tropes about what an artist should be, what a feminist should be, trying to deprogram myself of some second-wave feminist stereotypes that didn’t really fit for me, working through my own pansexual challenges of looking at what motherhood and sexuality could look like, and just offering a journey through a complicated set of moments where there were so many small things felt extremely charged.

I’m hoping that by slowing down those moments and allowing players to work through them, they can see the underlying structures and expectations that still remain around who should be a mother and what a mother should be, and how hard it is sometimes to resist those things. But how powerful it can be if you do and manage to figure out a structure that works for you. I would say I’m in a space where things sort of work for me.

In terms of tangible gameplay and what that looks like, you play through a point and click first person narrative experience. You play through a series of vignette moments, working through the point-of-view character (who’s basically me), their inner logic, their decision-making. But while there is certainly some agency within the game, there are limitations to that agency because at the end of the day, you are going to have a kid. So yeah, it’s somewhat linear in that way.

Juliana: I think it’s really interesting, for lack of a better word, to gamify some of that with Designing Motherhood. Half of our team doesn’t have kids, and a good number of people who experience the show, or own the book, or read the book, or engage with the Instagram account also don’t have children. Motherhood can mean a lot of different things, but usually the intro text starts with “birth is a universal experience.” There are some shared elements to this. And I think, hope, and imagine that your game will offer some moments to both shed light on and provide context and perspective that even people who maybe don’t end up having a kid can understand and empathize with those elements or see themselves in motherhood without necessarily having a child. You can birth in a lot of different ways, too.

Angela: Yes! That’s really important to me about the project. And I think also because I had for so long been quite comfortable with the idea of not having kids and wanting to also create space for so many of the women I know who have decided not to have kids, have felt in some way shamed about that decision. Creating space for those perspectives is really important to me as well. And it’s also in dialogue with transmasculine parents and non-binary parents who loathe the term mother in itself and the baggage that comes with it. So trying to grapple with all of those things.

It’s also definitely for the people who have not felt represented by other media about parenthood, the people who have gone through these experiences and may feel a sense of solidarity that they’re not alone in this bizarre encounter they had with ten breastfeeding consultants coming in, or a 72-hour induction gone wrong, or conversations around the genetic testing experience, and the difficult decisions that you’re asked to make sometimes without a lot of knowledge or explanation. In those moments, I hope that people who have gone through them will feel some recognition as well.

[ID: A white, u-shaped table displays numerous objects in a gallery space. The part of the table we can see reads “6. Milk”. This section of the table displays a number of bottles. A glass case next to these contains several breast pumps.]

I think of exhibitions as arguments put together in space, so what works go alongside each other and how you talk about those is very similar to how I might structure an argument in an essay, or examples I might pull together.

Kate: I’d love to hear from you, Juliana, because I’m not super familiar with curating, about the background labor that goes into a completed show and how that might or might not overlap with Angela’s experiences, with the research-intensive process that you have.

Juliana: It really depends. I’ve worked on a lot of different kinds of shows, but I think one of the main misconceptions about being a curator is, 75–90% of the work is administrative work. It’s not that there isn’t thought and concept that goes into it, and there’s a ton of problem-solving as well, but there’s a lot of care in that administrative work in figuring out what a budget looks like and what you can do with the amount of money you have and how to prioritize, at least for me, paying people and paying artists over some other elements. Unfortunately, budgets can be zero sum, and you have to kind of pick and choose, and that’s some labor and care that doesn’t always get recognized. But my process changes a lot depending on the project.

I am trained as a historian, so I’ve worked on some really historical shows that are object- and theme-centered that I’m going through an archive for, or exploring an idea through designed objects. Recently I’ve started working more with living artists, and that’s a much more collaborative process. You can’t really collaborate with objects in the same way that you can collaborate with an artist — telling them what I’m thinking about and asking for what work feels relevant to them, or when it’s a solo show, having an artist physically come into the space and shape how work is put on view. So there is definitely research and elements of relationship building, but I do think the administrative labor often goes unrecognized and honestly undervalued. I have a lot of training, and I could be doing a lot of other things with that, but I choose to do this because I care very deeply about the work that artists are making and the conversations that can be had through exhibitions.

I think of exhibitions as arguments put together in space, so what works go alongside each other and how you talk about those is very similar to how I might structure an argument in an essay, or examples I might pull together. I think that labor isn’t always recognized or valued in the same way, but I am grateful for the ways that it allows me to build relationships with artists like Angela.

Angela: And I’m grateful for all of the behind-the-scenes work that was done to support the At Play installation because oftentimes a curator is just like, “We need this work. Send the file. We’ll project it big, we swear.” Oftentimes I don’t get to even see some of those shows, especially if they’re in Europe, so it’s sort of putting things into the ether and hopefully receiving your wire transfer.

The amount of care and labor that went into allowing me to create this new updated version of [Don’t Leave Me] and making it work within the space was super appreciative and generous. It was a delight working with you. Thanks for all the behind-the-scenes stuff to make it happen.

Juliana: Artists often recognize it, I think.

Angela: There’s a difference! (laughter)

Juliana: Yeah, exactly.

[ID: Juliana, a woman with brown skin and shoulder length dark curly hair, smiles widely at the camera while crossing her arms. She has bright red lipstick and is wearing a black long sleeve shirt.]

Juliana Rowen Barton

She // Her // Hers

Providence, RI

Juliana Rowen Barton is a curator and cultural organizer based in Providence, Rhode Island. Through her research and projects, she explores the confluence of race, gender, and design and invests in community-engaged creative practices as a vehicle for social transformation. Currently, Barton is the Director of the Center for the Arts at Northeastern University, where she oversees interdisciplinary arts programming including Gallery 360. She is also part of the curatorial team behind Designing Motherhood, a first-of-its-kind exploration of design and the arc of human reproduction. She has been the recipient of numerous awards and fellowships, such as from the Graham Foundation, CASVA, ACLS, Center for Curatorial Leadership, and Mellon Foundation. Throughout her career, she has worked on exhibitions and programs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, ArkDes, Center for Craft, Wolf Humanities Center, Center for Architecture, and the Museum of Modern Art, among others. Barton comes from a family of architects and spends her free time in the pottery studio and the kitchen.

julianarowenbarton.com

Instagram: @julianabarton

[ID: Headshot of a cisgender woman with short purple hair wearing a yellow, black, and white tile-patterned shirt. The woman has pink tinted skin and dark red lips with a high gloss finish.]

Angela Washko

She // Her // Hers

Pittsburgh, PA

Angela Washko is a media artist, filmmaker, and experimental game developer who creates new forums for discussions about feminism in spaces frequently hostile towards it. Washko’s practice spans interventions in virtual environments, performance art, media installation, documentary film, and video games. A recipient of the United States Artists Fellowship, Creative Capital Award, Franklin Furnace Performance Fund, Impact Award at Indiecade, and Jury Awards for Best Documentary at the American Film Festival, San Francisco Documentary Film Festival, and Buffalo International Film Festival, her practice has been highlighted in The New Yorker, Frieze Magazine, Time Magazine, The Guardian, ArtForum, The Los Angeles Times, Art in America, The New York Times, and more. Her projects have been presented internationally at venues including Museum of the Moving Image, Centre Pompidou-Metz, Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, the Milan Design Triennale, Portland Art Museum, and the Shenzhen Animation Biennial. Her recently completed feature-length documentary film, Workhorse Queen, has won numerous awards at international film festivals and has been broadcast on STARZ, Amazon Prime, AppleTV, and more. Washko is an Associate Professor of Art at Carnegie Mellon University.

angelawashko.com

Instagram: @angelawashko