Between The Spaces

of The Sayable

“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” – Octavia Butler

9–10 minute experience, or the time it takes to spin around the block.

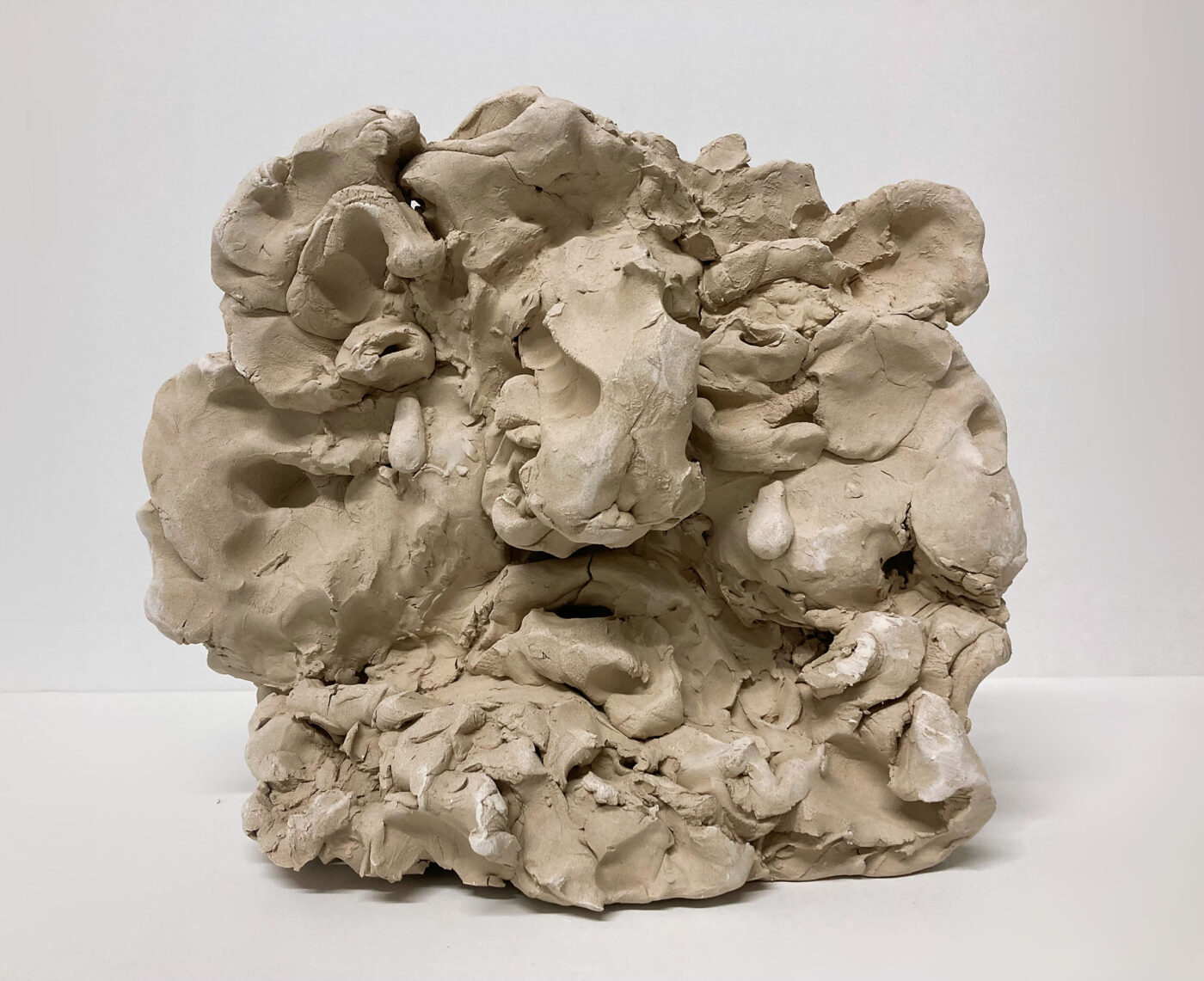

Simone Kearney’s richly textured ceramic works straddle abstraction and figuration to visualize emotional worlds, evoking a sympathetic response in the viewer. As a visual artist and poet, she is equally attuned to materiality of language and clay in her explorations of the body’s affective states. In this Q&A, we ask Simone to expand on the ways her practice is guided by touch, the surprising ways materials and words are in relation with one another, and how emotions touch us from the inside out, in ways seen and unseen.

A Q&A with SIMONE KEARNEY

Kate Blair: One of the central concerns of this issue is the idea of “feeling something out” or using touch as a means of deepening understanding. This seems especially true for your practice, which also has a focus on “feeling” in an emotional sense. How is your practice guided by feel for where the materials take you? How does emotion guide or show up in your work? Is there a relationship between the two?

Simone Kearney: I think a lot about the pace of thoughts and images in the mind. “Feeling out” with material in my practice is very important in that it is a way for the speed of image or thought in the mind to get weighted, like a balloon, to a ground of some sort, a ground that has a different pace, a pace of matter. I think for this reason, the hand is crucial to my practice.

I like touching as a way of thinking and feeling. I’m going to say feeling from now on, but really I don’t know the distinction between feeling and thinking most of the time — sometimes the difference is great, and sometimes they seem almost the same.

Working with clay consumes the hand in a particular way. It is the ground the body moves over all day long. It is what is below the body. I think the hand knows this and responds to it. Clay makes an emphatic and very simple demand on the hand. While I like to work in many different mediums, and I also write poetry, I have gravitated at times most especially towards working in clay as it is related to emotion because of this. Also because of its relative passivity as a material. It is very responsive. And for that reason it’s conducive to recording the immediacy of felt experience. It is a generous archivist and seems as though it wouldn’t interfere so much with what is being expressed through it. It can be a good ventriloquist. It is like a copyist. But then it refuses in its own way. And most certainly has a voice of its own.

“Feeling out” with material in my practice is very important in that it is a way for the speed of image or thought in the mind to get weighted, like a balloon, to a ground of some sort…

[ID: Photo of a large tower-shaped sculpture made of white and red clay, with many lines and markings scratched into the surface, and bits and squiggles of hand sculpted clay attached. There are small finger-shaped holes resembling windows, and a door at the bottom.]

Kate: Do you find the textures of the different materials (clay, words, paint) speak to one another? How do they teach you different things when working with them?

Simone: I love to think about each medium’s texture and how they speak to one another. In my new book of poetry, DAYS (Belladonna Press, 2021), I write a lot about language and its gauziness. In fact, in many ways I see the book of text as a textile — language is a mesh — and in that sense I might, in another project, turn to woven fabrics or literal textile as a way to further my thinking about language.

But language can also be brittle, or sludgy, in which case I might turn to clay as a way to more fully explore feeling out the consequences of understanding this. In the same way, the way that clay might collapse under its own weight when the structure gets stretched too thin — its waterlogged or too-thin texture — might serve as a metaphor for words, or images in the mind. What happens when the sentence gets too stretched out? What happens if the image in the mind is water-damaged?

I find that working with actual material helps me understand the materiality of language, and vice versa. But also, the brittleness of, say, dried clay, can teach us about the brittleness of a particular stance towards the world. The malleability of it when wet might tell us about the malleability of the human spirit.

I find that working with actual material helps me understand the materiality of language, and vice versa.

[ID: A photo of the artist during her time as artist in residence at Artshack Brooklyn Ceramics, posing behind a large, coiled vessel made of red clay that is set on the table in front of her. She wears an apron and a face mask. Pieces of wet clay are laid out beside her.]

Kate: I loved reading your collage of notes on touch for your piece, Metaxu. One of the things that stuck with me was the idea of the porous surface, the veil or screen as a metaphor for the ways people relate to one another. How do you think about the surfaces in your works? What kind of decision-making process goes into whether you leave finger marks behind, whether you choose to glaze or not?

Simone: Yes, I often think about the surfaces and qualities of surface that could serve as metaphor for spaces and experiences of subjectivity and intersubjectivity. I didn’t glaze my ceramic sculptures of crying heads which were on display in a show at Olympia Gallery in New York City recently, because the rawness of the emotion — grief — that was expressed, demanded a kind of porous, vulnerable, unglazed, and pure-earth surface. They were not yet ready to stiffen into glass (which is what glaze becomes), whereas I did glaze some of the ceramic sculptures in my show Amok, at Artshack Gallery in Brooklyn this spring.

I was thinking that there is something interesting that happens, for instance, if I glaze a figure of a sad and abject-looking figure who is in a semi-complete state, full of dents made by my fingers, only somewhat emerging clearly as a figure, or barely clear. To glaze that amorphousness, that state of being in the process, was appealing to me, because it could serve as a metaphor for how we put on a show, how we wear our personas, and how what we present to the world, becomes a kind of glaze. Or maybe the glaze serves to protect some of these sculptures who are at times a little emotionally fragile. All these surfaces are metaphors, in a sense. To gloss over, to be sealed, to be porous, rough-hewn.

[ID: A sculpture of an amorphous, abstracted face made of gray clay. Finger marks and pinched bits remain on the surface, leaving a rough, varied texture. The eyes, mouth, and bulbous nose nearly blend in with the rest of the surface features. A teardrop falls from each eye.]

Kate: What is tactile about emotion, about language? In what ways does your practice explore the touch of words?

Simone: Touch is a site of pleasure and sharing, but also of shame and devastation (don’t touch that, you shouldn’t have touched that, you shouldn’t have gone there). It is the beginning site of many wounds; it’s where we’re implicated; it’s the site of guilt, the fingerprint; it’s how we know something intimately; it sometimes leads us — our hands — in directions that contradict our minds, contradict logic. It’s also the site of creation — it’s how I write my poems, make my art, for instance.

Touch has its root in the Old French word “tochier” which means to “hit” but also “deal with,” so there’s the violence in the word, the idea of force, but it’s also about negotiation, proximity, encounter. Other senses of the word from the fourteenth century have to do with “to border on, to be contiguous with,” and this is something I’m also aware of, how touch is so much about relationship. Touch in many ways is both site of, and dramatization of, questions of relationship.

I’ve long been obsessed with the tactility of both emotion and language. Emotion can call attention to the body in that it is often felt first not as word but as sensation. It presses down on the esophagus, clamps the lung, is a jitter in the stomach, heart, mind. Because emotion often is bereft of words, or sometimes it resists words like oil to water, it is necessary for me to find correlatives in touchable mute objects and painted or drawn textures that the hand can read better than the eye.

Emotion can call attention to the body in that it is often felt first not as word but as sensation.

[ID: A hand-shaped sculpture with a human figure sprouting out of the end of each finger. The sculpture is covered in a shiny metallic glaze. Each figure has its arms bent at the elbows, reaching toward its stomach. The faces portray different expressions: a sneer, frown, a peaceful smile, a look of boredom, an open-mouthed shock or surprise.]

Kate: Your work confronts the messy in-betweenness of emotions and unnamable feeling-states. Do you ever find a tension between naming an emotion and allowing it to be undefined?

Simone: The reason I felt the need to be an artist as much as I felt the need to write poetry is because both — art and poetry — deal with the unsayable, the barely sayable — they both acknowledge the limits of language, though in different ways. I don’t mean to harp too much on the failure of language: I’m all about what can bloom between the spaces of the sayable, and specifically between the spaces that words create. And sometimes words can press on the world and release it like an essence.

But nevertheless, I wrestle with all that’s unnamable — it is the mesh, the taut atmosphere that engulfs each thing, that each thing rings with, like a reverberation.

I think life is about this tension between naming what we feel and letting it dwell in ambiguity. I do believe in the importance of letting the emotion become clarified by a word — to name a thing, as I said, is so often to liberate it. A lack of words can really oppress a feeling. And yet, I also am interested in nuance, in gray areas, since that is where a lot of richness and truth lies. And in the half-light of words or non-words, or in the cool dimness between names and no names, what aspects of experience might finally be freed?

[ID: Simone, a white person with blonde hair and sunglasses, looks away from the camera.]

Simone Kearney

She // Her // Hers

New York

Simone Kearney (b. 1984 in Dublin, Ireland) is a New York-based visual artist and writer whose practice primarily includes ceramic sculpture, drawing, painting, and text. Kearney is interested in tracking the daily experience of embodied emotional and intellectual life, which she traces through repetition and variation, metaphor and material. Her practice is an inquiry — as much visual as it is psychological — into how experience is always a cobbled fragile thing, shapeshifting, being configured and then reconfigured, subject to time, funneled and infused in and through our bodies.

Her book DAYS (Belladonna, 2021) is a text comprised of fragments that build to form a kind of textile, a mutable, fidgeting feminist work. She has also performed and created visual translations of various texts in collaboration with the artist and writer Sophie Seita and has published writing and interviews in The Brooklyn Rail, Public Journal, and Lit Hub, among others, and recently published a conversation with Jarrett Earnest about her work with Belladonna Press. She has exhibited work in galleries across New York City.