“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” –Octavia Butler

20–30 minute experience, or the time it takes to look through old photographs.

Designer Mindy Seu and artist Mimi Ọnụọha are prolific collectors, but they’re not necessarily archivists. Keenly aware of the selection and curation within digital archives, Seu and Ọnụọha are also technologists, and it was under this shared context that we brought them together for a conversation about their proclivities, including indexing, spreadsheets, and writing by hand to remember.

A CONVERSATION WITH

MIMI ỌNỤỌHA AND MINDY SEU

Jessica Ferrer: To begin, could each of you talk about the kind of archives you’re interested in and why?

Mindy Seu: You want to start, Mimi?

Mimi Ọnụọha: Absolutely not. [laughs] Mindy, all you.

Mindy: [laughs] We’re setting the tone here! When I was reviewing these questions earlier, I thought, oh, do I actually dig into “capital A” archives? I have with some projects, but in many cases I don’t. I almost feel like a professional listener. I really deal with oral histories and conversation and grassroots archives.

There’s so much textual documentation about “capital A” archives and who it includes or excludes. While we have access to those types of spaces through various privileges, I still find myself drawn to unrecorded histories and compiling them on my own. I feel like Mimi, you’re in the same world, but I’m curious if you work in any formal archives.

Mimi: I feel similarly. I was thinking about actual archives, and I have worked with some, but they don’t often stick with me in a deep way. I’m more interested in the practice of archiving and what it suggests.

I find it much more fascinating because there are all these different ideas that are presupposed by an archive. The most important one is what you decide to include in the first place, but that’s invisibilized by the final products. You don’t have to think about that decision. Archives also suggest you have a world where there’s a lot of content that is produced and flowing, and then what you fix and save is what matters.

There have been groups in different times who have believed that, in a world where so much is fixed, what you let go of is what’s most important. And so I think what I like about archiving is how it becomes a way to understand a larger context and think about meaning-making within that.

Mindy: I feel the exact same way. When engaging with formal archives, I always start by questioning the archivist or the institution around it. One of the reasons why I resonate with your practice is I feel like we actively try to foreground the subjectivities of this collecting process. They’re not meant to feel like an objective truth or history.

The “capital A” archive is one where it has some generational preservation in place, and I don’t have archives like this. After we’re gone — when we’re done with the project or we’ve moved on in other ways — the archive itself, the collection, is much more fraught. I don’t think the durability is there. Because of this, I wonder if I’m more of an indexer, even though I’m often relegated to archival studies.

Mimi: You said that you feel like that durability is more fraught afterwards than it is during the time that you’re working on it. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

Mindy: Everyone wants to be the innovator and no one wants to be the maintainer. Or rather, maintenance takes resources. When I am actively working on a project, I have the energy and resources to maintain archival or collection-based projects, but what about ten years? In fifty years? And these are some of the timescales that many of these archives exist in.

[ID: A yellow ochre metal file cabinet sits on a white podium against an empty wall, its drawer is open and holds many folders.]

Mimi: I think you’re right. I think maybe some traditional archivists might raise their eyes a little bit at us doing a conversation on archiving. We come at it from askance, a little bit, but I’m more interested in these questions that surround us. These questions around durability, maintenance, collection, what isn’t seen as important, really the process around it. I’m interested in how you’ll draw your distinction between “capital A” archives versus indexing and collecting, which to me feels a little bit lighter, faster, and more flexible, and which is maybe what I am drawn to in some ways.

But I will say, having said all this, I have made work that truly is drawing from archival content and using that as a way to, again, think about the distance between what was valued in a time versus what is valued now. And yet somehow I don’t know that I describe myself as an archivist or one who’s deep in the archives.

Mindy: Well, I love your distinction between noun or verb. I think the process of archiving, of collecting, is something that I really resonate with. Tressie McMillan Cottom has this great quote, “Essays are a public.” Maybe we approach it this way, too. It’s not for the sake of collecting or preserving disparate objects or artifacts, but rather trying to figure out how those activate a larger conversation, discourse, event, or the like.

So for me, the process of collecting almost feels like a proxy for all of the social activation that comes around it. I really agree with this verb component. I love the process and the activity surrounding the thing.

Mimi: Yeah. And there’s something you’ve said that just resonates with me because I feel like this in a lot of my practice, where I’m like, the thing is not the thing.

Mindy: It’s the pointer!

Mimi: Exactly! Jenny Odell has this little line that I just really love where she talks about how you look at one thing and then you look deeper and it’s actually three things and you realize it’s a thousand things, and the more you look, the more it is. But for the purpose of talking about something, you need that one thing. But that’s just like you said, it’s a pointer. It’s not the full story. And I feel very much like this when it comes to the whole topic of archives in general.

I think about the difference between filtering and slicing and taking a piece, not the whole. All of these are forms of organization in a way, and these are forms of meaning-making.

Jessica: Hearing you make that distinction between archiving and indexing is one that I was really interested in teasing out with you. Moving into indexing like searchability, categorization, organizing archives of any kind, “capital A” or not, what are those potentials or pitfalls? What do you love about indexing? What do you find frustrating?

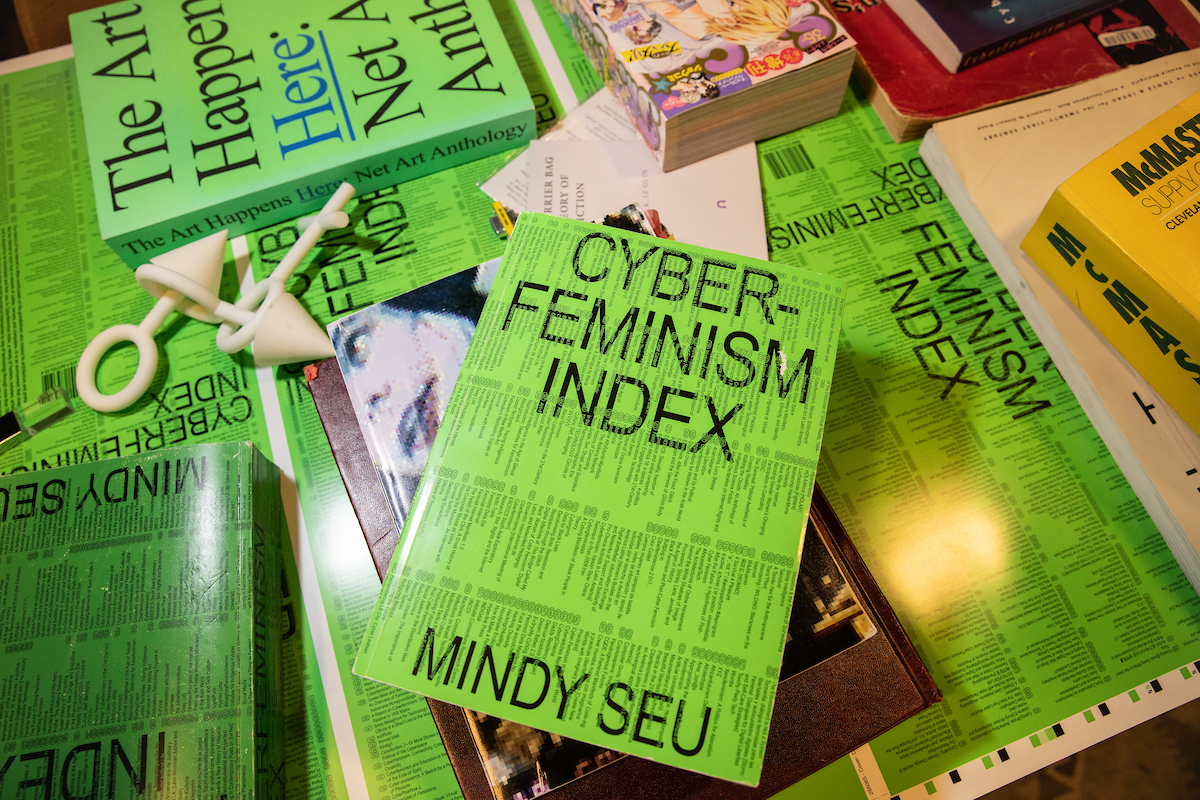

Mindy: Well, when I was working on the Cyberfeminism Index, my publishers wanted to call it an archive in the title. We talked about this a lot with my collaborators, and it just did not feel right. And so I’ve tried to unpack the difference between an index and an archive: an archive is always pulling in. It’s taking external objects and bringing them into an internal container. It tries to maintain the holistic object. Whereas an index is always pointing out. It’s almost like an annotated bibliography.

In the Cyberfeminism Index, each of the entries is essentially an excerpt or still or proxy that points to the original source where you can find the holistic thing. Unless it’s something really short like a poem or a manifesto, the majority of the text is actually outside of the container. If anything, I felt like it was my job to maintain that external link, like creating a permalink, a clone, an alternative way of maintaining that source. So I personally connect more with index as pointer rather than an archive. How would you distinguish it, Mimi?

Mimi: I think because you were working on the Cyberfeminism Index, you had to think about it really deeply in a way that I haven’t had to, so I’m glad you are saying that. It’s actually really helpful for me. I think that’s a good distinction.

I think about the difference between filtering and slicing and taking a piece, not the whole. All of these are forms of organization in a way, and these are forms of meaning-making. I’m the kind of person who really likes to make a plan so that I don’t have to follow it. Making the plan helps me feel like I’ve taken something unruly and made some sense of it. But that doesn’t mean that is actually the right way or that’s the only way. It’s just a practice that helps me feel a type of way so that I can move forward and hold the fact that this world is so much more unruly than what I can handle.

There’s something in this that makes me think a bit of Sylvia Wynter, the Jamaican theorist, and this way that as humans, we do have a tendency to confuse the part with the whole, and confuse the specific with the universal. And I feel like what you’re gesturing to here is a way of holding that. Saying, no, this is a piece. The larger thing can’t fit here, so I’m just going to point to it. We can’t contain it. That’s it. To me, Jessica, that gets at that answer, the potentials and the pitfalls of it.

[ID: Neon green books are scattered on a work table that read “Cyber-Feminism Index” at the title and “Mindy Seu” at the bottom of the cover.]

Mindy: Well, this idea of reorganization for me also comes down to the media. Different media have different affordances. Filtering, in some ways, has a very digital connotation. But there’s also, of course, forms of analog sorting or these types of cross-references that might feel very digital, like a hyperlink, but have analog origins, like an index or bibliography. And then within all of those, there’s also these conventions that we’re actively trying to break.

So even though a website is easily sortable or searchable by keyword, you also want to figure out other serendipitous forms of finding. Sometimes a keyword search is extremely limiting. What if you don’t have the right syntax? This is also probably a more tactical way to address this idea of pitfalls and potentials. The pitfalls are that there’s these existing conventions and affordances, and then the potentials are maybe breaking those things or trying to highlight them.

Mimi: Yeah, I appreciate this. I see what you’re saying. What I want to hold is both sides of those where you’re like, there’s a convention, but actually that convention can be really limiting so sometimes we can change it. I think I move between those all the time. Even data, for example. In a very strange way, I love spreadsheets. I love organizing data.

Mindy: I love spreadsheets! [laughs]

Mimi: Truly, truly love it. I’m like, I love putting it together. [laughs] I like it because I just recognize it’s like I’m organizing a tiny corner of the world. But in the actual world, that doesn’t work for everything.

Things don’t just have places. Everything leaks out. I’m really drawn to that tension. That’s why I like to make a plan and then don’t end up following it. I want both.

Mindy: Well, I think that we think about structure in a similar way. I love spreadsheets, I love organization, I love a good durational plan, but these things are scaffolding for improvisation. I will never follow the plan to a T, but knowing that there’s guide rails gives me a lot of peace.

Mimi: You don’t have to follow the guide rails at all, but there’s something about the practice of creating them. It’s like a false security or something, but it’s a very generative one. I’d go so far as to say — to invoke Sylvia Wynter again, and her thinking that we need to understand what it means to be human — I think this is a very human thing, to create a framework. The hard part is being able to switch away from it or adjust it, or to realize that it’s flawed. It’s necessarily flawed.

And so in a way, I feel like both of us, Mindy, are talking about making this a practice: the practice of creating and then abandoning and then recreating it, and then abandoning again, and then recreating. It’s the back and forth between that where magic happens. We make room for that improvisation.

Mindy: It’s like we’re creating our own rules just so we can break them. [nods] Works for us.

I’ve tried to unpack the difference between an index and an archive: an archive is always pulling in… Whereas an index is always pointing out.

Jessica: When you’re organizing a project, how do you collect your thoughts there? And then also, are there personal archiving practices that you guys maintain that help either directly or indirectly with your artistic practice?

Mindy: Well, I would say in life, I’m very organized. I’m the kind of person that loves tax season because everything’s already sorted and ready to go. I just hand off my spreadsheet and organized files to my accountant. [laughs] But I think part of my interest in collection is because I have a really bad memory. I’m a very active notetaker. When I’m reading something, if there’s a quote that resonates, I’ll immediately transcribe it and add it to a Google Doc or an Are.na channel or something so I can refer back to it later. And I think even if at the time these things feel really small, when you then look back on it, they piece together to this larger whole. In retrospect, I was subconsciously making a project finding throughlines before I even realized it was a seed. Having these cues of creating some document or record has been a good strategy for me — I need to have some artifact of it just as a way to remember.

Mimi: I don’t think I realized the extent to which I do this until you were talking. I’m the same way. I use Are.na, I use Airtable, I use Notion. I use so many things just to save and collect. I have a lot of ins into making different projects, but one of them is collection. It’s taking things and being like, this feels similar to this. I’m just going to put this here. I’m looking at a literal folder I have where I’ve been putting receipts for something. I don’t know what it’ll be, but just something about having it all, putting it there; that act is very, very useful for me. So that is a thing I often reach for, too. And same as you, when I read things, I have a whole practice I don’t even think about it. I take a photo of it and then I upload it somewhere.

Mindy: Exactly.

[ID: Four panels of identical video stills capture hands sorting through a conveyor belt of red and purple tomatoes.]

Mimi: What I often see is that I’m circling around an idea for months without realizing that I am. It doesn’t really matter what tool I use for it; I use so many different tools depending on what it is I’m trying to do. But there’s something about the act of collection that feels very innate to me.

At the same time, there’s something I want to tease out. I grew up mostly here in the Global North, and my family is from the Majority World. We’ve got different ways of thinking about information and how you hold it. I remember planning this big event with my family. I had everything organized: here, here, here, this, this, and this. But it wasn’t working with my parents. They were just like, what is this? They also work very thoroughly, they’re very organized, but I realized it’s just not in the same way. And I think it was something I was taking for granted as someone who operates in a certain space and field. My mom organizes things in her head, but it’s very organized. She doesn’t do anything external. And so when you’re talking to her, it’s like you have to draw it out. She has the full picture, and then it’s like how she speaks, it’s almost like that’s the filtering.

And so there’s something I’m still trying to wrestle with, my extremely external impulse to take everything and collect it, put it here, put it there, versus hers, which is to take it, and then it will filter later. There’s something there that I don’t know if it’s interesting, but it’s something that just comes to mind. I don’t know if this reminds you of anything, Mindy.

Mindy: This is fascinating though, because I’m jumping with this to move in —

Mimi: Jump!

Mindy: Who knows what this is, right? But I’m going to give a sweeping generalization and start talking about gender roles and domesticity. As you were describing this, it was a clear association to “mental load”. How when you’re trying to structure the duties and runnings of a home — I don’t even know if your mom did this, but I’m just making assumptions here —

Mimi: Make it.

Mindy: They don’t have a project manager. They don’t have these larger structures or office tools that are making note of this thing, so they have a calendar of every single thing that needs to happen and it’s internalized. And you don’t even see it as labor because it’s running so smoothly. Even onboarding someone else to try to do some of this feels more difficult because you then have to translate this process to them. “Mental load” is very gendered and segues into a lot of different aspects outside of the home, too.

Mimi: Oh yeah. I definitely think so. And there is a case to be made about this. I think you’re right. That describes my mom to a T. And I think that in a way, externalizing some of these things makes what could be internal more visible so that more people can actually be on the same page and know what’s happening going forward. And there’s something about it that’s like, cool, that feels like it’s actually countering this very gendered way that labor is distributed. So there’s something really great about that on one hand.

A lot of things that have to do with technology, data collection, the internet, I think for a lot of people, those seem very abstract. They feel really removed. Putting it in terms of the body grounds it.

Mindy: I have a question to build on this for you then. Your practice of collecting or creating these external buckets, does that only exist for projects that are meant to be externalized, that are meant to be viewed by the public? Or do you also do this for a personal thing that no one else sees?

Mimi: I would say I do it more for personal things.

Mindy: Wow.

Mimi: Much more. But it’s in a different way. It doesn’t have to be legible.

Mindy: Sure. Only to you. Yeah.

Mimi: Yeah, I know exactly who it’s for: it’s for me. In a way, it’s like I can be less careful. It’s like when somebody cleans a room, but you’re like, now that you’ve cleaned it, you’ve ruined it. I know it was messy, but I knew where my mess was. It’s a little bit like that.

I think sometimes I’m at odds with these tools of capitalistic productivity, hyper management of everything, entering some of these other spaces.

Mindy: Well, I think I’m also like you, where whatever I do for these external projects, I do probably tenfold for myself. I journal in spreadsheets. But I will say, even though I am generally an internet cave dweller, and I love being on my computer all the time, I have really found that moving outside of the screen for me has been very important. Not even in an efficient way, but in a clarifying way.

Now, whenever I have to write a paper or an essay, I’ve started handwriting it first. Having that specific time — Claire L. Evans, an amazing internet writer as well, and a musician, brought this up. They started writing their essays by hand. You literally have a visible association between the words coming out of your finger, it’s embodied. Whereas when you’re typing on a screen, you’re not looking at your fingers on the keyboard, you’re looking at the words on screen. So there’s an actual mind-body split between the words and yourself. This practice of literally taking notes, adding it in a notebook, and then transcribing them, it’s like multiple methods of hard coding the information, and I’ve realized that or else it will disappear.

[ID: A light brown hand is pointing to a line in a book. The title reads “2015” in black text. Each paragraph on the spread has a neon green number above it, the title of each project, and a website link.]

Mimi: Yeah. I see what you mean. Look, I always have to write my notes. I really do. But what she was saying reminds me of Toni Morrison. I cannot remember for the life of me where, but Toni Morrison used to talk about this. Toni Morrison wrote all her books by hand, which is wild because some of her books are long. But she said that she could always tell when somebody typed their manuscript first rather than writing it by hand. Basically, there’s filler when you type because of the affordances of the medium. It’s so easy to type versus when you have to write; you filter in your head first. That first step has to happen internally, and then you translate to your body.

Mindy: That is so true. I’ve never heard that articulated, but that makes a lot of sense because you write so much slower than you type. So sometimes I have all these thoughts, but getting them onto paper, you are forced to pre-filter and structure the sentence in a certain way. That’s really helpful.

Mimi: Yeah. I hurt my wrist recently. I physically cannot write in the same way I would, and it has totally changed how I take notes and how I think. To your point about this connection with the body, I’m building this muscle of, I don’t know, holding meaning in smaller phrases? There’s something I’m doing that I have to adapt to that, again, gets at these affordances of the technology and the medium.

Mindy: It’s amazing how our bodies will adapt because maybe now that your wrist is hurting more, you naturally create a shorthand or a different way to notate. It’s cool.

Mimi: Yeah, we’ll see.

Jessica: I’m also a longhand note taker and weaver with looming carpal tunnel syndrome, so I feel you. But both me and my mom are hardcore. She still keeps a Filofax.

Mindy: So cool. Wow. [laughs]

Thinking about analog technology versus digital technology almost feels like a misnomer because every single digital technology we use has some material presence.

Jessica: Since you’re leaning into this space of human touch and invoking the senses, I’m curious. Mimi, you have a piece called the Cloth in the Cable, which wraps internet cables in hair, cloth, dust, and spices that hold significance in Igbo culture. And then relatedly, Mindy, you’ve described the internet as an environment that shapes and is shaped by its inhabitants. Why is it important for you to emphasize human touch and invoke the senses when talking about data collection or other kinds of collection in technology?

Mimi: I feel like for me, it’s pretty simple. A lot of things that have to do with technology, data collection, the internet, I think for a lot of people, those seem very abstract. They feel really removed. Putting it in terms of the body grounds it. It brings it back to earth. It makes it visceral.

Particularly around media art or whatever you want to call it, what I always wanted was for people to feel the work in a different way. For it to have a viscerality and to be like, yeah, these things are connected. It’s not just your mind. How you internalize an understanding of something in your body is just as important. And so for me, thinking about anything related to tech, if I’m interested in it, it’s because there’s some way that it feels very real and grounded to me.

Mindy: And technology was analog first. So thinking about analog technology versus digital technology almost feels like a misnomer because every single digital technology we use has some material presence.

I wrote this essay for Source Type a few years ago called “The Internet Exists on Planet Earth,” trying to map the global supply of the materiality of the internet. When we start to think of it this way, our phones are basically dumb rocks made of rare earth minerals that are mined in areas that have little to no governance. It’s extremely oppressive. We have fiber optic cables under the ocean floor. Sending an email has a carbon footprint. Everything has some material impact. When you hear people say AI is so bad for the environment, maybe that feels abstract, but it’s because these server farms require so much energy, so much water for cooling. This was the primary critique when the blockchain conversation was happening a few years ago. But I just feel like if people were to actually understand how much physical labor goes into maintaining these very ephemeral technologies, it would really help this conversation around environmentalism and climate collapse. It’s so integrated.

Mimi: Yeah, period. Honestly, there’s nothing more to add. Absolutely. Focusing on the materialism of these things, I think it brings us back to the conversations about actual responsibility. It just brings us back to thinking about things that are really important.

[ID: Four panels of identical video stills capture a Black farm worker operating a harvesting tractor through a field of cotton plants.]

Jessica: I feel like even over the course of this conversation, you’ve helped me understand more. Digital things, the internet, they have a body almost. They require a crazy amount of hydration to cool. And those cables you could describe or argue as veins. I feel like there’s that extended metaphor that you guys are reaching towards in your practices of stop thinking of this as not an active thing or something that just exists without a physical imprint.

Mindy: Well, and to that point, it really points back to these naturalistic metaphors that we have in technology. We call the internet “rhizomes” because of the way it’s modeled after rhizomes of nature, we call [data storage] the cloud because it feels really ephemeral. Computer bugs were physical first; it was a literal moth that Grace Hopper’s team found. These naturalistic metaphors shape how we use tech and how digital technologies are built.

Jessica: Totally. I think that leads into my next question around how the aesthetics of an archive can have implications about its contents potentially, or do they? What might the aesthetics of an archive imply about its contents?

Mimi: I think not that much, basically nothing. [laughs] I think they imply a lot about the creators of the archive more than anything. And I think that with archives, it is extremely important to think of these as things that are created by people for a purpose.

It’s the same with any kind of technology: it’s created by people, for people, for some kind of purpose. And doing that helps you be able to trace it. It helps get away from this feeling; I think that lots of folks can easily feel really trapped or lost when we’re talking about tech. And adding some sense of intent, but also materialism, and also a sense of none of this was inevitable, doing that really helps pin it down. It makes it so that we can see it a little more clearly.

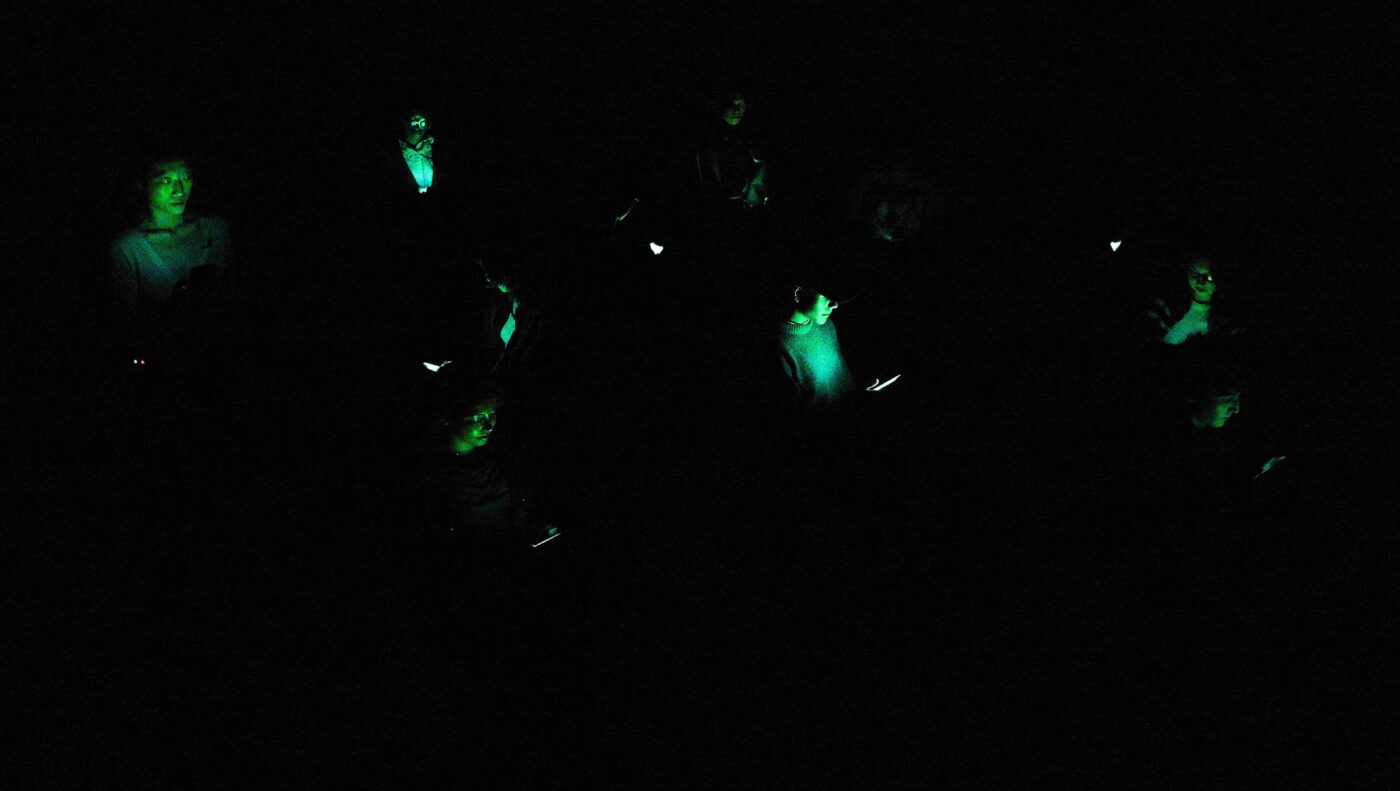

[ID: People are gathered in a dark room looking at their phones as they emit neon green light, illuminating their faces.]

Mindy: I think you’re right about how it says a lot about its creator and not about the contents. I think that’s spot on. It reminded me of this quote that my former thesis advisor in grad school, Jeffrey Schnapp, told me, which was, “To anthologize is inherently violent.” To anthologize, to collect, to archive, you are pulling something outside of its original context. You are removing it from its natural flow. Maybe there is new value that’s created by recirculating things and recontextualizing them, but we have to understand that to preserve something means that it was removed from a specific environment. I think that natural life cycle is something to make note of here.

Mimi: So what did and what do you do with that notion?

Mindy: Well, I think that’s why I’ve really gravitated towards internet artifacts. Because within the digital space, archivism is really about duplication. Trying to create emulators, clones, duplicates, permalinks, or something like this. And even now, if you’re trying to archive a physical object, there’s ways of modeling it and having some sort of digital replica, but allowing the physical thing to live on its original site.

Or I think maybe there’s an agency to this. Like the Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, for example. Everything that they house was donated by a self-identified artist. The artist is actively choosing to change the object’s life cycle. This is what comes to mind. But again, I’m a material minimalist and a digital hoarder, so it’s a very different process for me.

Mimi: I really see what you’re saying about how in a digital sense it’s more additive. You can add all these additional contexts. It’s not that same rupture. But then when we’re talking about physical things, there is that something was here and now it’s been placed in this other space. I think that it’s especially true with the understanding that when you put something somewhere new, it’s not like it cuts off. It then becomes a part of a new context, too.

Mindy: Yeah. Totally.

Mimi: And then that creates things as well.

Mindy: All relational.

Jessica: Before we close out, are there any burning questions that y’all wanted to ask each other?

Mindy: Well, I just wanted to say this is exactly how I hoped this conversation would go, Mimi. [laughs] Again, because I’m so familiar with your work and we’ve orbited around each other, the fact that this conversation was so energetic and free flowing, I was like, okay, cool. The parasocial indications were correct.

Mimi: They’re correct. Mindy, we already knew each other! It just makes sense. I feel the same way. It’s funny, I feel very familiar with your work, and so it’s great to meet you as connected to and separate from that at the same time.

Mindy: For sure. Yeah. So thank you Jessica and USA. Spot on. Good curation.

Mimi: Really!

Jessica: Thank you! We love hearing when it pans out this way.

[ID: A woman dressed in a white button-down collared shirt poses. Streaks of platinum blonde braids frame her face.]

Mimi Ọnụọha

She // Her // Hers

Brooklyn, NY

Nigerian-American artist Mimi Ọnụọha creates work that questions and exposes the contradictory logics of technological progress. Through print, code, data, video, installation, and archival media, Ọnụọha offers new orientations for making sense of the seeming absences that define systems of labor, ecology, and relations.

Ọnụọha’s recent solo exhibitions include bitforms gallery and Forest City Gallery. Her work has been featured at the Whitney Museum of Art, the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Mao Jihong Arts Foundation, La Gaitê Lyrique, Transmediale Festival, The Photographers Gallery, and NEON, among others. Her public art engagements have been supported by Akademie der Kunst, Le Centre Pompidou, the Royal College of Art, the Rockefeller Foundation, and Princeton University.

Ọnụọha earned her MPS from NYU Tisch’s Interactive Telecommunications Program, where she has taught as Assistant Professor. She is a Creative Capital and Fulbright National Geographic grantee. Ọnụọha is also the co-founder of A People’s Guide To Tech, an artist-led organization that makes educational guides and workshops about emerging technology.

mimionuoha.com

Instagram: @thistimeitsmimi

[ID: Mindy is looking at the camera, posing casually against a blank wall. They have light brown skin and dark hair that is past their shoulders. She is wearing a fitted turtle neck with a vibrant pattern.]

Mindy Seu

She // Her // Hers

They // Them // Theirs

Los Angeles, CA

Mindy Seu is an artist and technologist based in New York City and Los Angeles, whose practice focuses on technology-driven performance and publication. In 2023, Seu published Cyberfeminism Index, a pseudo-encyclopedic book that gathers three decades of online activism and net art. It was commissioned by Rhizome, awarded the Graham Foundation Grant, and underwent an international book tour with eighty-nine performative readings across eighteen countries with sold out events at the New Museum, Whitechapel Gallery (London), Amant Foundation (Brooklyn), and Lafayette Anticipations (Paris), among others. Seu will begin touring a new lecture performance called A Sexual History of the Internet in Fall 2025. Her latest writing surveys feminist economies, historical precursors of the metaverse, and the materiality of the internet.

Seu has lectured internationally at cultural institutions (MoMA, Barbican Centre), academic institutions (Columbia University, Central Saint Martins), and mainstream platforms (Pornhub, SSENSE, Google). Her work has been featured in Vanity Fair, Frieze, Dazed, i-D, and more. She holds an MDes from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and a BA in Design Media Arts from the University of California, Los Angeles. Seu is currently an Associate Professor at University of California, Los Angeles in the Department of Design Media Arts.

mindyseu.com

Instagram: @mindyseu