“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” —Octavia Butler

25–30 minute experience, or the time it takes for a midday stretch.

For more than thirty years, Wenceslao and Sandra Jo Martinez have operated Martinez Studio, a container for their individual and collaborative practices of weaving and painting. Initially, we approached them to talk about sampling in weaving — the process of testing out different yarns to see how the materials respond to different conditions. But when sampling with handspun churro wool, the artists note a central tension between maintaining a sense of play in the weaving process while also planning with a material that is increasingly difficult to come by. The talk of material led to a deep dive into the conditions and experiences of those doing the labor of spinning wool, and the reciprocity of care needed to maintain critical avenues of cultural exchange.

BY MARTINEZ STUDIO

Kate Blair: For starters, I think I’d just like to hear from both of you — from you, Sandra, about your painting, and you, Wence, from your weaving perspective, how sampling operates in your practice.

Sandra Martinez: The sampling thing for me personally is that all of the paintings and drawings are generated from a journaling, automatic drawing process. So they are inherently a sample of that place and time, those emotions. There’s various layers. So every time I go at something, it’s another recording of another day.

But what it really is doing is also in the gallery — because we run our own gallery — so clients and collectors are talking to us directly; it ends up encouraging all the humans to make things and to make in a very light-hearted, playful way, to not worry about being a professional, being a hobbyist, showing it to anyone, that it’s inherently healthy for humans to make things no matter what they’re using.

Wenceslao Martinez: Sampling, for me, is mostly the material, because when I dye the yarn, I dye batches of yarn, of colors. I would spend three or four days just dyeing yarn, but not dyed for a particular design or as a sample. It’s a more free-form painterly building up — a group of shades of blues, reds, whatever — so when I have a project, for example Sandra’s designs, then I can go and choose what colors to use in the work. So it’s pretty much that way. I never actually work making a sample of a weaving to present somebody as a sample as they go, I make the piece itself.

Sandra: My visceral reaction to the question of sampling in a traditional fiber way of thinking about it, that you would make something to justify that you’re going to make this other larger, bigger project — Wence and I have always been basically a mom and pop gallery. We don’t work with institutions or work to justify gaining a grant to realize a giant project where we have to prove to you that we’re going to achieve this with samples and giant plans. We make intimate things ourselves. And then nice people take them home, and they live with them.

So we’re really out of the loop. We don’t work with interior designers. We don’t work with dealers, we don’t sell through other galleries at this point. It’s an end user collector connection to us that is so intimate, that when someone is making a commission, we can discuss what tones — do they like more turquoise green? Or do they like a deeper indigo blue? Wence can dye some wool to hit that note, but then there’s a conversation about an understanding of release to us that yes, that is the main color, sure, but there’s going to be a lot of color change and nuance and things that you have to trust the artists to give you.

Wence: Especially because the materials that we use, it’s handspun, natural colors. So there’s a lot of variations on the natural color itself.

Sandra: Before you dye it.

Wence: Before you dye it. So you can’t have a flat blue, exactly the same as the sample. So let’s have variations, which to me, and to us, it gives life to the piece. Naturally, you know?

[ID: Several large wooden looms are lined up in a studio space. Blown-up images of abstract paintings and previously completed weavings are propped against pillars in the room, positioned where weavers standing at the looms will be able to see them while working.]

It’s inherently healthy for humans to make things no matter what they’re using.

Kate: When we were talking before, part of your visceral reaction to the topic of sampling, it seemed to me, was about the nature of over-planning versus play in the practice. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about that.

Sandra: Even though we work in completely different methods and materials, we both have that desire that the actual making be as close as possible to our flow, to have nothing get in the way of playfulness. When things are over-planned, I think we both tend to feel that there’s a stifling quality to it, that I don’t want. I want ultimate freedom in my making. In fact, that’s one place in our lives where we absolutely have complete freedom.

To protect that autonomy and the freedom and the flow, we both just have set that up as part of the way we work. Wence isn’t dying specific colors to make this piece. He’s dyed and done, playfully, for weeks, dying all kinds of shades, so that when he’s ready to make the choice, the choice is in the moment. It’s a flow, you don’t have to stop, set up all your dye stuff, delay for weeks, because you want to get the exact right orange. We don’t do elaborate sampling, and then mark down how much quantity of this or that made this color. In the moment we enjoy creatively responding to the moment. And then I think you feel that in the work. Because the work is not made according to a tight plan. There’s a general skeletal structure, and it unfolds, whether it’s in the painting or in the weaving.

Wence: I think that play with material, with the design, it’s always there without even thinking about it. Because, again, once I have all these colors, and you go to choose the color to weave this particular piece, then you start playing with the colors, like in some parts in this detail, it’s got two colors twisted together, two lines working. So that’s play to me; you forget it’s work. You think you’re just making, you’re having fun. So it’s always like that — weaving, dyeing wool, designing, even, it’s like that, because ever since we’ve had a computer, I’m able to take photographs of my work and take parts of one piece and come up with a whole different new piece. That’s playing to me; sometimes, it’s just too much of playing, that I think once I am done with this, I’m like, Okay, I need a break from this now. So it’s like, we have that flexibility that is incredible, but I don’t know, maybe most others can’t. But we do have a lot of fun.

Sandra: We protect it, too. We really have protected it strategically. So that we can say whatever we need to stay in a storytelling moment; we can go into all the detail we want to, culturally, or, in my case, empowering other people just to make stuff. Don’t worry about this, this is not precious. You can’t touch it, or you’re wrong, or you’re stupid, because you don’t understand the declarative nature of my work and what I’m trying to unpack to you, and you aren’t getting it.

No, we want to release people to find their own joy in this activity. Because globally, forever, since day one, we know that humans want to make stuff, and decorate stuff, and play with things, to color their house, even if it’s cow’s dung and white lime, and those are all you have to work with — you want to decorate, you want to play. And so we are champions of reminding people that that’s a really good thing to do. Even in weaving, which can be a rigid format, Wence maintains all of that same play.

And then that gets passed down to the assistants. We need you to learn how to play instinctually. We want to encourage you to trust yourself as you play with these materials. So we become the old-timers cheering on people feeling free and feeling entitled and empowered to explore their world, whether it’s what they’re making or what they’re thinking and learning about inside.

Wence: Not too restricted, just free flow.

[IDs: 1. A colorful weaving of an abstract sun shape with wavy planes of bright blue, red, green, and orange. The top and bottom of the weaving are stabilized with a white band and fringe. 2. Image of the reverse side of the weaving with the colorful threads hanging loose.]

Non-visual artists have difficulty trying to squint at a graph drawing with colored pencil of a proposal.

Sandra: Wence has started blowing up life-size photographs, lifesize to what the weaving would be. And a recent weaving that was a really well done one by our daughter and another computer-generated design of Wence’s so that the assistants can see in the studio, the goal: This is what we’re reaching for. It is so different from when we use a sample photograph this big to achieve a work big, this big and bigger. Now you’re looking at a life size thing. It has given everyone so much motivation.

Wenceslao: Because trying to explain to the assistant how I want the piece, where I want the change in this little tiny photograph, it’s difficult. But when you have blown up the size of the weaving itself, you can see, you can even measure how far you can go from one color to another color to blend the two together. So that’s another part that’s just new to us.

Sandra Jo: Oh, brand new. It’s only in the last couple months.

Wenceslao: Yeah, it also does the sampling thing.

Sandra Jo: Another sampling thing with Wence is that ever since we got a computer, somehow Wence has the tech genes. I’m terrible. And so when Wence really figured out that he could play around — because he’s also a photographer, so he knows how to do Photoshop and all that business — that he could play around with his own patterns and generate new designs off of that. It’s been an explosive opening for you.

Wenceslao: Especially because sometimes there are collectors that want to commission. And it’s a lot easier for them to see that I can put the design together — what the piece is going to look like. Because before then I would do it by hand, and people would be like, I’m not quite sure.

Sandra Jo: Non-visual artists have difficulty trying to squint at a graph drawing with colored pencil of a proposal. But when you take chunks of a photograph of weaving, and combine it so you know, hey, don’t don’t look too close. But generally it’s going to look like this. And they go okay, fine. Here’s your money.

Kate: So you’ve been using a sample that’s computer generated out of previous photographs of weavings.

Sandra Jo: Yes, especially because it’s a geometric design, a pattern design. So it lends itself to chunks.

Wenceslao: Yes, yes. It’s been very helpful for me and for the clients.

Kate: It’s very interesting. I also have another question. Why did you choose to make the scale of those images bigger? Or what led to that decision?

Sandra Jo: Oh, you mean, the sample photos we’re doing.

Wenceslao: Because like I was saying, to explain to the assistant, that this is how it should look. Versus when we’re looking at tiny photograph, you know, I’m saying this, we have a mock up of just lines.

Sandra Jo: It’s called a cartoon, it’s an outline on a blank piece of paper of the main lines where the weaving is going to be divided up and notes. But that’s a big line drawing. And then the photographs we would use, you know, we could only get eight and a half by eleven. So how did you come up with going giant with the photos?

Wenceslao: Well, the way I thought about it — I’m having a hard time explaining to my assistant, that I’m thinking, okay, what if I blow it up to the size, then you can actually see really when the color starts changing and how it changes because sometimes it’s so subtle that you can’t see, you can’t really see. But some of these colors up here have already started integrating from the beginning, just a little lighter here.

Those are the things that are learned in school in Mexico City when I went to weaving school. So then blowing this up, it’s a lot easier for me to communicate with the person. Then I only have one part to explain, the technical part, how to do it. But they can see where the change is, where to do it.

Sandra Jo: You know, now that weavers can go right up to it with their hand and go, okay, how much? How wide is this? You know, you don’t need elaborate tools. It’s like, oh, okay, I can see that.

The material itself is getting hard to find because the younger generations are not going into spinning.

Kate: You split your time between Door County and Santa Fe. Is that correct? Between those different environments?

Wenceslao: I do split my time between Santa Fe here, just go here for a couple of weeks. And then we’re heading off to Wisconsin where we have another gallery in Door County. But because winter’s so harsh, I’d rather be in Mexico, I have another studio. So that’s where I work in the wintertime. And also it’s a lot easier to source my yarn, my materials and stuff.

Sandra Jo: Our home studio in Oaxaca is in Wence’s native village. So it’s home. It’s on the side of the sacred mountain in Teotitlan del Valle, it’s beautiful. But we’ve had the gallery in Wisconsin for twenty-nine years. We have to keep that going because we want to throw the 30th party — so plan ahead next year. And then Santa Fe, this is our fourth year. So I mostly stay here to run Santa Fe, which is more year round, pop in and out of Oaxaca. Wence will pop in and out of here. I’ll pop in and out of Wisconsin, hopefully this season. But much to our surprise, we are now really stretched.

Wenceslao: The other big part of me being in Oaxaca is that I work with the spinners, because a lot of the material I use is handspun. And you know, I’ve been buying material from this village since I was a kid. So I have at least forty years of going back and forth. And I become a part of the family sometimes, you know, they’ve invited me to have a cup of coffee with them. And talk about life, like their family. So far last year, I think I lost three spinners because they’re getting up there and COVID came and lost quite a few over three years. Some of the material, like natural black and brown, is getting hard to find. And also, the material itself is getting hard to find because the younger generations are not going into spinning.

Sandra Jo: There’s so much weaving that gets done in Wence’s home village, Teotitlan. But a giant proportion of that is done with mill-spun wool, in many cases even pre-dyed. Because material is expensive. And to use handspun wool, it’s logistically difficult. And there’s so much more washing. It’s more difficult to dye, the processing of it, the unevenness of it, the different tones — you get a whiter sheep, a yellower sheep, a grayer sheep. And so when people are really living on production, they need to get it done so they can be paid. The lesser materials are easier to source. The spinners that Wence goes up in San Baltazar Chichicapam this is a big effort. But it’s a familial, connected relationship of support that Wence and we take very, very seriously. We want to support them. It’s a beautiful, ancient relationship.

Wenceslao: They expect that from me, and I do expect the material from them, too. So it’s a mutual thing that we help each other. It’s just something that I’ve always thought about since I was a kid. The kind of work I do has the integrity of using 100% handspun Churro yarn from Oaxaca. You can’t find any other piece that’s made out of all handmade materials and handed-down everything. Even the tools I use, they’re handmade.

Sandra Jo: Even the looms are handmade. It’s a beautiful thing for us to keep that legacy route because it feeds into all the conversations that we have in the gallery with the end users of this work. It brings a depth of understanding of how many hands, how many humans and how ancient this beautiful — and weaving is a global legacy. So it opens their minds to all of this connectivity, and it makes for a really warm opening of their hearts towards indigenous cultures in general, by just repeating to them that we hold this material and process so precious that we’re committed to these things.

Wenceslao: Yes, but also we’re lucky enough, fortunate enough that we have collectors that support that work because otherwise we won’t be able to do what we do.

Sandra Jo: We really find that a lot of our work, all the artwork you do, is combined with all of your life experience and all the other things that you do. Because thirty years ago, where we lived, no one wanted to put craft in a fine art gallery, and no one knew what to do with my abstract automatic drawing stuff on paper. So we opened our own gallery, and we are also our representatives on the floor. So when you come in and talk with us, you’re getting a cultural download that is much deeper than the actual object in front of you. Because when we get our work as artists in front of the viewer, and that circle is closed, and someone’s looking at it, we want that not just to end with that’s a cool thing I want to see in my living room, we want it to also be something that opens your heart and advances your curiosity and your warmth towards people you don’t know, stories you couldn’t imagine, which is how I felt about it.

Wenceslao: Yeah, I think most of our collectors have that kind of relationship with our work, because they have met us, and a lot of them became friends. And they want to know every time they come and visit the studio gallery, they want to know what’s going on in our lives, how our kids are doing. We have created a really nice relationship with our clients.

Sandra Jo: And it’s another part and parcel of being an artist. I think you need to not be afraid of commerce, you need to not be afraid of promotion, of telling your own story, of finding a way to get out. Because you need to and you can do it. We did it. If we can do it where we were, anybody can do it.

[ID: An abstract weaving in earthy tones of blue and brown with abstract shapes reminiscent of a rock formation or a bird in flight.]

We are always threading needles with people about [their fantasies] about Native culture, about what the old days are like, about old systems of living.

Kate: Yeah, amazing. Thank you for that. I’m curious that less people are going into spinning. Did you mention that?

Wenceslao: Yes. The younger generation are not really into it. I mean, I dealt with families, and their daughters, especially because it’s mostly women’s work. So I go to the house and say, do you have anything? No, my mom passed. And so no, we don’t. Actually, they’re selling their tools now. Because they’re not interested in getting into it.

Sometimes I buy the yarn, and it comes in balls. You see on the outside, it’s really beautifully done. And then I take it back home and make it into skeins, so you can wash it, and dye it, and then find inside that the yarn is a lot thicker. That used to frustrate me, because I’m thinking there’s cheating. But now, lately, I’ve realized that somebody new is trying to learn how to spin. So, I think it’s a wonderful thing, because now I feel encouraged. That’s fine!

Sandra Jo: Somebody’s learning! It’s a good sign!

Wenceslao: We’re not gonna lose all of them. So that’s what’s happening. It’s less and less people who are spinning now. I used to go to the village, we’re talking about thirty-five years ago, I wouldn’t have enough money to buy everything I needed. And now sometimes I can only find two or three pounds. So it’s like, okay, you know, and then when I can find ten, and I’m talking about going house to house —

Sandra Jo: There’s no store.

Wenceslao: I go house to house — five different families, six different families, sometimes they have one ball, sometimes they have nothing. And sometimes I’m lucky to find somebody who has three pounds, like it’s really a good day when I find that.

Sandra: This village is an hour and a half drive up into the mountains from Wence’s weaving village. And you know, so for a spinner to really have ten balls of wool that they need to sell for extra grocery money, they’ve got to take a bus and spend their entire day on a difficult trip, no cars, of course, to get to the weaving village to sit at the corner of the market and hope somebody’s going to buy some handspun wool. Most of the weavers in the village are not really using that high-level material, so it’s a really tenuous relationship right now, and one that we are concerned about.

There will always be people, I think, who want to do some level of this. But what we’re seeing is a cultural shift from subsistence farming, and spinning a little wool on the side for cash, like in Wence’s village, subsistence farming and weaving, honorable, culturally-derived patterns, but tourist market weaving. It’s always something people do on the side for a little extra cash. But there isn’t as much of a drive to buy it from them from the village as there used to be. Now we just feel concerned about that shift, because you build a relationship with these people and these other communities that are involved.

Wenceslao: We depend on each other. They depend on me going to buy from them. I depend on them. It’s getting a lot easier though. Even though the ladies, some of them don’t speak Spanish. We speak our language, Zapotec. But Zapotec is a different dialect. So we can’t really understand each other, but they have cell phones these days. And then they can communicate with the granddaughter. Is Grandma home? Does she have anything? That’s how I can communicate with them.

Sandra Jo: It’s such a beautiful thing to have an eye-to-eye relationship with the beautiful human who spun the yarn. You’re not in a store. It’s the same way that collectors say they feel when they come in and they talk to us directly. You’re talking to the person who’s making this. It’s a beautiful thing. I once, you know, because I’m the outsider — went along with Wence to the village, and we go door to door to the houses that he knows and nobody has anything, but it’s been a big long day of getting there, so we go to the town’s corner store and pay a fee for them to do a loudspeaker announcement all over the village: “Hey, there are weavers here from Teotitlan and they’re looking for gray wool.” All of these women come flooding out into the streets with baskets. They’ve got two balls of wool, three balls of wool. They all come flooding to us in the center of town. There’s not one ball of gray wool. But we bought everything because of course, you’re going to buy everything. But it’s incredibly potent for me, as a Midwesterner from an apartment building, to be that close to a person who’s taking this time to do this spectacular thing that is going to get all the way through all these other things and become this thing. It’s beautiful to be so deeply, humanly connected.

We depend on each other. They depend on me going to buy from them. I depend on them.

Kate: That’s really beautiful. I also have a question about that, just that if you do have trouble sourcing those materials in the future — what are your plans around that?

Wenceslao: I will try to find a different village. Some villages up in the mountains, far up, I hear that they spin with natural fibers. But one of my one of my goals is eventually to actually go find the raw material. And find spinners and a different village, maybe.

Sandra Jo: Are you talking about, when you say the material, get fleece, and give it to a spinner?

Wenceslao: Get fleece — raw off of the sheep. Yeah, because I know some places, other villages, where I see sheep. So it’s just a matter of having time to go to the village, find the owners and say, I would like to buy your fleece.

Sandra: Oh, buy the fleece! because some of these spinners are running out of —

Wenceslao: Running out of material —

Sandra Jo: And sheep.

Wenceslao: Also they’re older, they don’t want to go find the source. They don’t have sheep. Maybe fifteen years ago, they introduced another breed that’s called Peal-Away. They don’t have wool, they have hair. So short, [some are] just raising them for food. So that means this sort of sheep is kind of disappearing.

Sandra: Well, because these are free range. You take your animals out on the mountain, you let them go. So in the States, people who had little coats protecting their sheep so that they could spin that and sell those to a specific person because that sheep, Bobby, is the right color. And we’ve got to put a little coat on him, so the sun and the prickers don’t get in there. In the village, they’re running around the mountains free, which means that they are interbreeding, which is the concern that the Churro might be affected by inbreeding of this Peal-Away sheep that is not intended to be spun at all. Those are weird, natural things that happen in a specific environment that I don’t know how we can affect, or —

Wenceslao: Change that. No, I mean, I don’t get it, because if they’re not interested in selling the wool, if there’s no market, why bother? Because it’s a lot of work to shear them off, wash it, clean it.

Sandra Jo: If you’re not going to use the wool, it’s very uncomfortable for the animal, sheep that are really used for spinning true as long fiber. It’s not good for the animal either. So now you’re not using the animal for the proper thing. And so you’re not using the wool.

And also, how do we properly honor the fact that humans in these cultures are suddenly being given other opportunities for how they want to spend their life? Education is happening, a vision of, I am not tied to this life. I have to celebrate that too. I’m a big ol’ white girl. I want to see everybody have opportunities to grow and be outside of where they were placed when they were born.

So as adults within the system, we have a lot of feelings. And we don’t have any control. We only can respond lovingly, but it’s a real mix. Oh, we don’t want to lose the old ancient culture! But that kid should go to school. What if she’s going to be the president of the country? You know? Why should you spin, you know, why shouldn’t she do everything? Anything?

Wenceslao: Yeah, change happens. Nobody can stop that.

Sandra Jo: It’s a little bit of a slippery slope that we walk because we engage with the collectors so much about the cultural issues. So we are, on the one hand, just in love with all the most ancient connections we have to these materials in this thing, this legacy, at the same time, have to be —

Wenceslao: We try to encourage the younger generation to go to school. So it’s kind of a difficult balance.

Sandra Jo: What I was thinking about with the collectors, sometimes, is they get into a vacation fantasy relationship about ancient culture, especially if you’ve gone to Oaxaca, you engage with this stuff for the first time. And it’s all so sparkly, until you’re the kid who has no options, because you don’t have any school past sixth grade, and all you can do is go out into the mountains and watch the sheep. And you don’t have an opportunity to break out. And so, we are always threading needles with people about [their fantasies] about Native culture, about what the old days are like, about old systems of living. How beautiful is it to see the women grinding the corn on their knees on a volcanic molcajete, because they got to make tortilla by hand on a woodfire, where they collected the wood. That is a beautiful fantasy photograph op for tourists. But the reality of that human is why the women don’t weave in the village.

Until recent generations, women didn’t have time. They could help spin, they can help manage, clean, make bobbins, all of that. But time spent on a loom — when you take that much time to provide food and wash the clothes in the river for your family’s basic needs, you have no option. And so we’re always trying to gently educate the viewers because a lot of people go off to Oaxaca for trips too. Be grounded, be centered, nothing is perfect, nothing is better. We’re all a blend of all of this fluidity within what we’re allowed to do, what we’re supposed to do, but we’d like to keep you in your lane, so you keep providing this beautiful, cultural thing. It’s all a soup. And we have to be gentle with our humans and our expectations, and our relationships to ancient cultures, especially when we go as a tourist.

Kate: Yeah, definitely. I’m hearing a lot of interesting threads in this whole conversation about just kind of responding to the moment. And I think that’s another really interesting way that you all are doing that, in art and in life. I think that’s wonderful.

Sandra Jo: I really believe it’s a critical component of what we do. Because it builds relationships, and it builds connection. And I just don’t think there’s anything more important than how we treat humans. And so that we’ve been able, because we decided to be in commerce, to have our own gallery, put a price tag on it, and sell the object, we take very seriously the relationships and what, gently, we can feed these humans, so that we build love, and we build connection in it. We take it quite seriously as a part of our work.

Wenceslao: We’re educating people here too. Like Sandra said, some people don’t even know where I’m from. But now they know. And they see. And unfortunately, in the US, things are a little difficult for the last few years, that people see each other as “Other.” But I’m a very lucky person because of my art. People see me differently when they know what I do, versus if I’m just an employee in a restaurant. So I feel like, together we build a connection. Art has no borders, and we feel like that’s what connects us with our viewers.

Sandra Jo: That’s how we connect with the viewers. There’s we even though we’re from completely different places, the minute Wence and I met, we really understood that we share the same need for this creative flow, for the inspirational moment, for finding a way to make our artwork so integral to our lives that we don’t have to find a way to do it. It’s part of every single day of every activity, even when it’s commerce, we’re still working on our artwork, and we keep it close, close. So we can feed off of that and encourage each other that you’re experimenting and playing.

Kate: We are closing in on our time, but I just wanted to make sure I ask if there are any final thoughts you had about the sampling topic before we close out.

Wenceslao: I don’t know what’s going to be next. But [sampling is] always part of our work ethic. Don’t you think?

Sandra Jo: The last thing for me that is a priority is this warm, playful attitude, not only towards our work when we’re each individually working on our stuff, a super playful attitude when we’re collaborating. When Wence is weaving something based on one of my paintings, [it’s a] super playful, trusting release. You know how to run with this with your materials and your process. This is only a starting point.

But then it’s still a playful thing when we’re working with people in the gallery and talking about the work. Because we meet them where they are, we do not expect them to know anything. Play in our work when we’re isolated in our studios and making the stuff and also the same attitude when we’re talking with people about it, which is all the time because we’re on our own sales floor. Yes, let’s open up a cornucopia of warm, fuzzy bringing-you-in, bringing-you-along, being playful with you as you’re a viewer. You’re never wrong in our place.

[ID: A man with brown skin leans on a wooden loom, smiling widely in front of a geometrically patterned weaving.]

Wenceslao Martinez

He // Him // His

Jacksonport, Door County, WI

Master weaver Wenceslao Martinez combines his Zapotec heritage with over fifty years of weaving experience to create contemporary tapestries from hand spun, hand dyed Churro wool. His life at the loom combines the weaving heritage of his birthplace, Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, Mexico, with his formal training in Mexico City under Bertha and Pedro Preux at Taller Nacional de Tapiz. He began training as a weaver at age nine with his father and grandfather and spent his childhood roaming local mountains, shepherding, and developing a love for the natural world. Pattern design, tonal variations inherent to undyed wool and desert landscapes continue to fascinate him today. Using traditional looms and Oaxacan hand spun wool, he elevates basic materials and ancient processes. He often works with his partner Sandra Jo to translate her Symbolist paintings into weavings. One of his greatest joys as a steward of his village’s legacy is mentoring the next generation of weavers in Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca. Wenceslao and Sandra Jo opened Martinez Studio in Door County, WI in 1994, a second location debuted in 2020 on Canyon Road, Santa Fe.

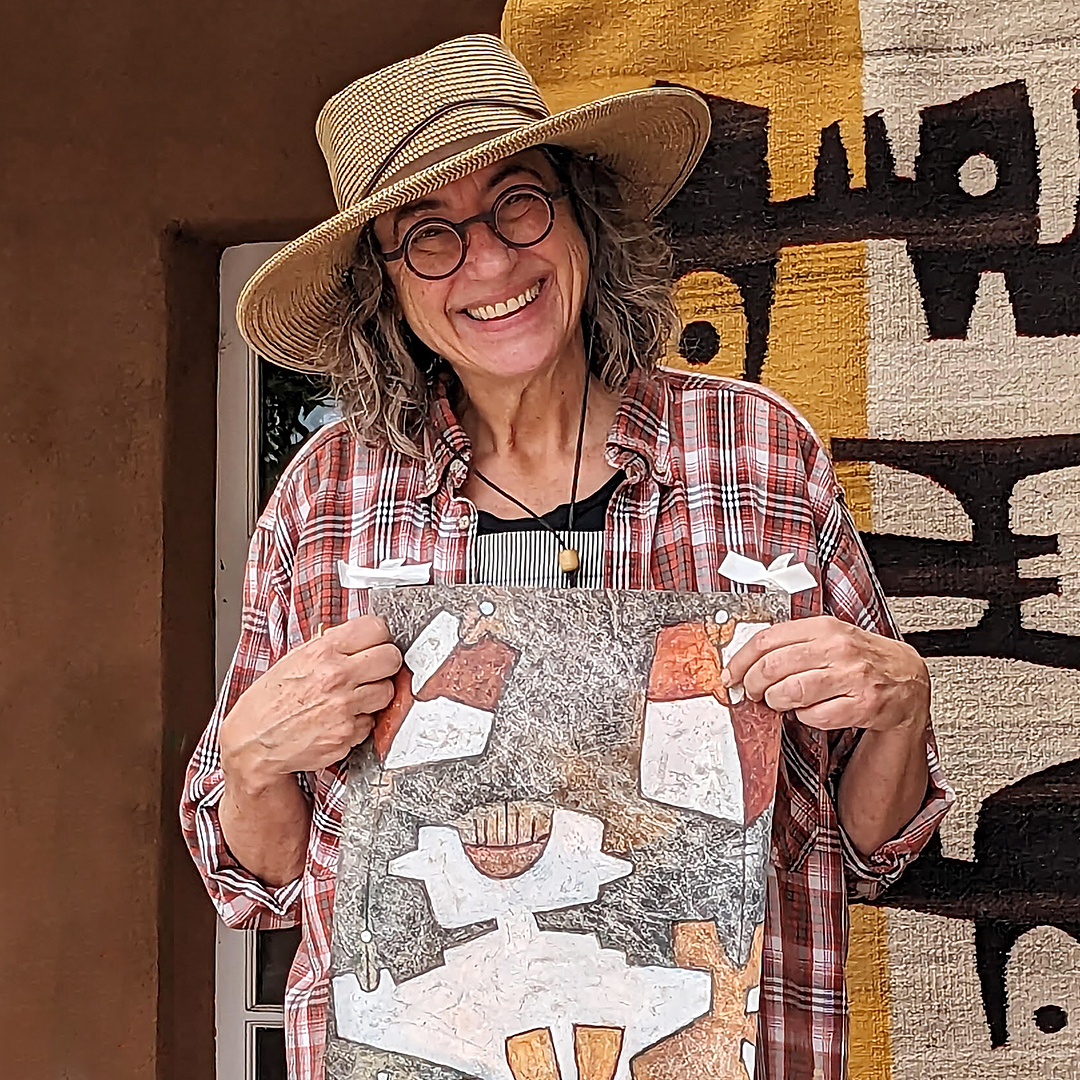

[ID: A white woman poses smiling in front of a weaving and holds an abstract painting across her chest. She is wearing a brimmed hat and black circular glasses.]

Sandra Jo Martinez

She // Her // Hers

Jacksonport, Door County, WI

A symbolist painter from Milwaukee, Sandra Jo Martinez’s designs evoke a shared human experience that points to our connective root. Connected to automatic drawing, what begins as stream of consciousness content, transitions into layers of ink, dirt, pencil and acrylic washes that reveal simplistic human, plant, and shelter forms. Her journaling process provides first and foremost, a vehicle for personal exploration, and seeds that may develop further in painting or weaving. At age twenty-eight, a friend suggested that her drawings would translate well into weavings. A weaver in Oaxaca named Wenceslao Martinez jumped at the challenge. At their first meeting in person in 1988, she commissioned fourteen new works, initiating a cross-cultural relationship and artistic collaboration that now spans thirty five years. Wenceslao and Sandra Jo opened Martinez Studio in Door County, WI in 1994, a second location debuted in 2020 on Canyon Road, Santa Fe.