“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” –Octavia Butler

40-50 minute experience, or the time it takes to cook a meal with a friend.

In this conversation, Selina Martinez, an architect, and Lydia Cheshewalla, an ephemeral artist, come together to discuss the potential of worldbuilding rooted in Indigenous belief systems. From their perspectives both as Indigenous people and creative practitioners, they consider how we respond to our surroundings when we are creating, and how these acts of creation go on to influence their environments. In doing so, they address the need to reframe our world and its diverse inhabitants as collaborators and the web of communities, both human and more-than-human, that must be considered in any process of making.

A CONVERSATION WITH SELINA MARTINEZ AND LYDIA CHESHEWALLA

Kate Blair: One of the framing questions for this issue is: what is the world that you’re trying to build? And I’m wondering if that’s a question that you contemplate in your practices. If so, how would you situate your practices in the idea of world building? Selena, do you want to start?

Selina Martinez: My background is in architectural design, and I would say world building is tied close into that as far as creating a concept and then actually being able to bring that to reality through a space that people occupy. The way that I would think about the world that I’m trying to build, specifically focuses more so on uplifting a plurality of worldviews. I think one of the things that, specifically in the industry that I’ve been in as an artist and as an architect in training at the moment, is representation and identity. And those are things that as an Indigenous woman, it is hard to come across. In this industry, the numbers are pretty low as far as registered, licensed architects for Native American slash Indigenous people; it’s like thirty registered architects in the US and like eighteen in Canada. So it’s pretty small.

Then that also comes with the contrast of — that is a hierarchical system that is constituting those numbers, whereas people in our communities have been building and have expertise and have been doing this work forever. So I think those are the things that come up for me when we talk about world building — really trying to push beyond that and beyond the status quo of how we build are things that I’m thinking about, and trying to find more relationality for community and how they use space. And as somebody who could potentially be contributing to nation building when it comes to my own tribe, some of the things I think about are: how are we connecting to our ancestors in the built environments and how does our built environment help us practice culture? And how do we see ourselves reflected in the spaces that we interact with in our communities? And how does that self-affirm who we are and the various ways we can be as individuals and as community?

Lydia Cheshewalla: Having an ephemeral art framework, or a framework that is rooted in ephemerality, I definitely do think that worldbuilding is tied into that, primarily because ephemerality to me is a reality of seasonal shift, is a reality of the cycles of the planet, is a reality of how we as humans experience loss and renewal. But in the contemporary mainstream belief system, the Western colonial belief system that is prevalent here on Turtle Island, we’re really pushed toward permanence, toward this idea of longevity that is static. And so for me, leaning into ephemerality and doing things like prescribed burning, practices that have been on the prairie for thousands of years, I’m really interested in the idea of building a world that is more in alignment with these rhythms and cycles of how — not just we as communities and as cultures function — but how we function in our relationships with all of the beings and forces on this planet, within the cycles and seasons of the weather, of the celestial bodies of our more-than-human kin.

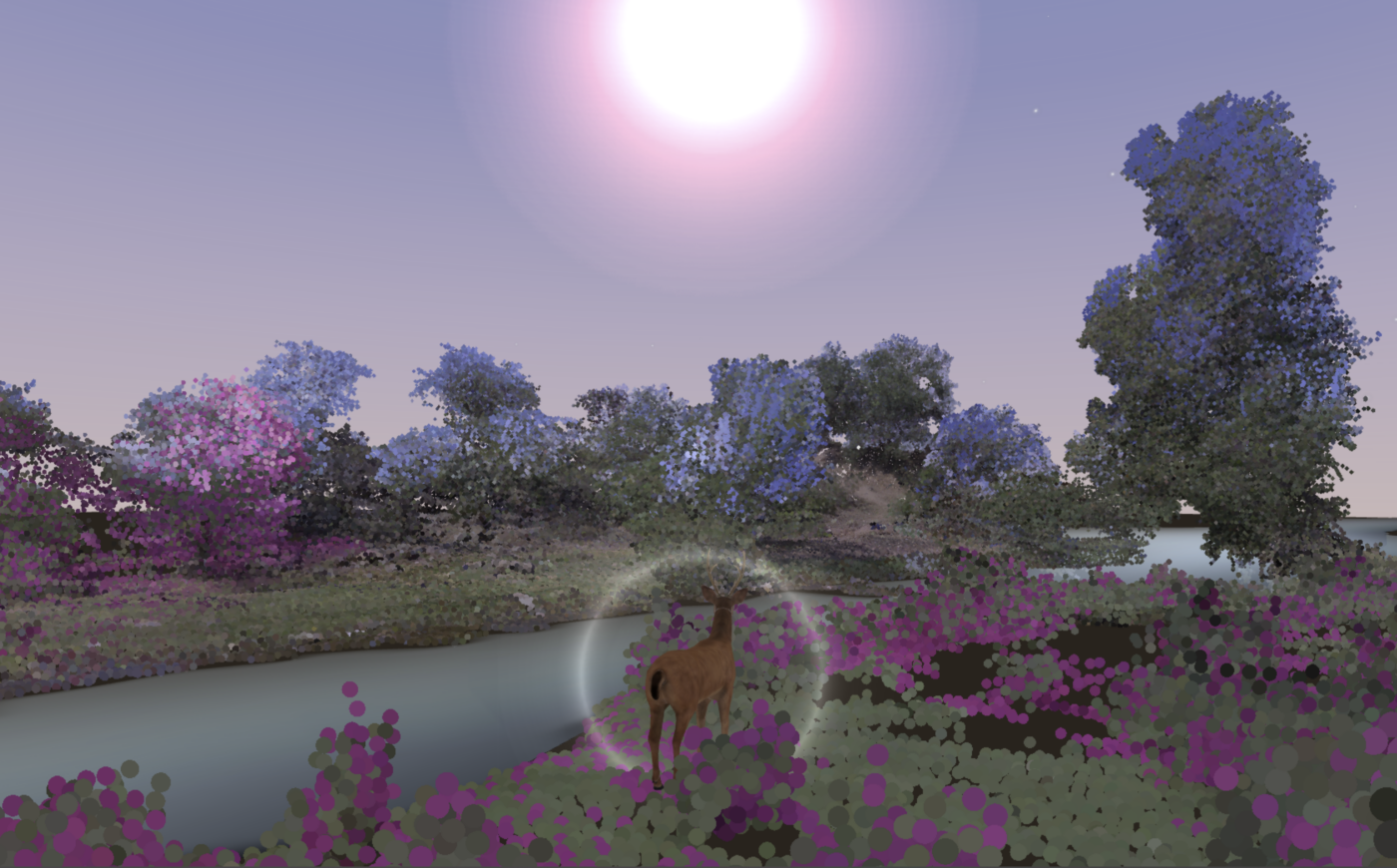

[ID: A digital image of a river landscape lined with trees dominated in painterly greens, purples and blues. In the foreground, a deer looks out at the water. The deer is enclosed in a glowing orb that mirrors the sun above.]

I’m really looking toward building a world that comes back into those relationships, that is even able to see those relationships again. Being in an urban environment right now, something that’s really prevalent is tree blindness, which is hilarious because they’re all around us all the time. How do you forget to see one another? So [I’m] trying to make work that is building a world where we remember how to see one another, how we learn to not just see one another, but to see one another as we really are, and in what our own needs are in agency, not asserting needs onto other beings or onto each other. So, building a world that’s more comfortable with that change, building a world that’s more comfortable with the acknowledgement that we’re not all the same being, but we’re all on the same home together. We’re all creating existence together. We’re all part of it. So how do we honor those things? And definitely thinking forward toward climate change — how are we building a world that can actually sustain life? How are we considering our actions and what are our value systems rooted in? How do we share those through our artwork?

Kate: That brings me to the next question, which is: I think architecture and an ephemeral practice both respond and react to the environment. You brought up climate change, and I’m wondering if that’s something that both of you respond to specifically in your work or, how you situate that within your practices also. Selena, did you have any thoughts on that?

Selina: So architecture and infrastructure in general are one of the bigger influences on climate change, utilizing major resources such as water and minerals and all these types of resources that we have to extract from the earth to just create a building and everything that goes into it, along with the infrastructure to support that. There’s a lot that goes into making a building live. And as far as how much I control within the industries, that’s very difficult, personally for me to be able to say that I can achieve that through the current system of how we practice architecture. There’s a lot of work to be done there, generally as an industry, on a personal level. And as an artist, I actually approach this through trying to reconnect, and I actually do that through teaching Adobe block workshops.

This is a more natural approach to creating and building in the desert. Other cultures and peoples have done this historically. Since I currently live in the context of Phoenix, I feel the impact of climate change because it’s extremely hot here. It’s about 120 almost every day now in the summer. And that’s something that you’re constantly reminded of whenever you step outside. So, [laughter], I don’t make the blocks during that weather, thank God. But I think that’s one of the ways that I’ve personally been trying, as far as architectural practice, to use that process. That building, the creation of those blocks as a way to reconnect to the earth as a natural approach to creating basically a block unit that can transform into larger design pieces, reflection spaces, walls, ovens, useful functional things.

That’s just one way that I personally feel like I can have control. And I share that practice and actually teach from the beginning to the block, laying the block and actually plastering the block, and have also been dabbling more into pigments as more of an aesthetic additive to that as well. So I would say that’s my personal response. I think it’s a huge responsibility to try and tackle it all. But that’s one of the ways that I’ve been able to explore that, but also share that as a resource with community here in the context of Phoenix.

The prairie ecosystem is a manmade ecosystem. It’s a built environment that was created through the repeated and intentional application of fire to land.

Lydia: I feel like it’s also good to note that contemporary Indigenous people are working with the materiality of our time that has been influenced over thousands of years in a way that has taken us away from the value systems our Indigenous cultures are rooted in. And so it’s really difficult, I think, for there to be an expectation on Indigenous people to just fix it, or to do better somehow when we’re working with the materials of our time and with mindsets that have been taking root over thousands of years. It does take walking back some of the prevailing culture, some of the Western mentality, colonialist mindset. It takes walking that back or maybe even forward into other belief systems. These systems won’t change until there are people whose hearts have changed.

That’s really what it comes down to; that takes so much more than Indigenous people. It takes everybody. And I think that Indigenous people, we have really beautiful ways of looking at the world, and we have really beautiful systems, but we did not make this mess. And we can’t be beholden to a higher level of resolving it.

For me, the way that I respond or react to my surroundings of the environment, I grew up in a really rural state, I grew up in Oklahoma. I grew up in the northeast corner of Oklahoma in Pawhuska where my tribal reservation, one of our districts, is located, and where the tall grass prairie is. It’s one of the largest remaining tallgrass prairie remnants in the world. And it’s one of the only places where the practice of prescribed burning has remained unbroken from Indigenous people to the settlers who then came into that territory.

The way that I respond and react to that environment is different than the way that I respond or react, say, when I’m in Chicago, which is much more urban. But I’ve also found that that earth relationship is always present because we’re always on the earth. It doesn’t really matter where we’re at, whether we’re situated in a rural place or in an urban place. We are of the earth and it’s all around us. There’s sky, there’s water, there’s dirt underneath concrete, which is just amalgamations of other forms of earth material, like is still earth. So for me, I try to just be observant of what is there. I think it’s really easy in urban environments to be like, oh, there’s nothing here. There’s just buildings. But I’ve seen so many very resilient plant kin breaking concrete to have a little bit of life.

And I think that’s like who I wanna be paying attention to. It also really makes me mindful of, like we build these structures, we build these prolific spaces, and then here comes like a tiny little plant that is just able to make its way anyway. So I think there’s something really beautiful about that, in honoring that we’re among so many different life forces. I’m always looking for that. But being in a more urban environment, I do think now I’m noticing more architecture. I mean, Chicago’s renowned for its architecture, and there’s so many interesting things happening here with greening architecture, which I think in its own ways can be problematic, but it’s also very exciting and dynamic as a thought space.

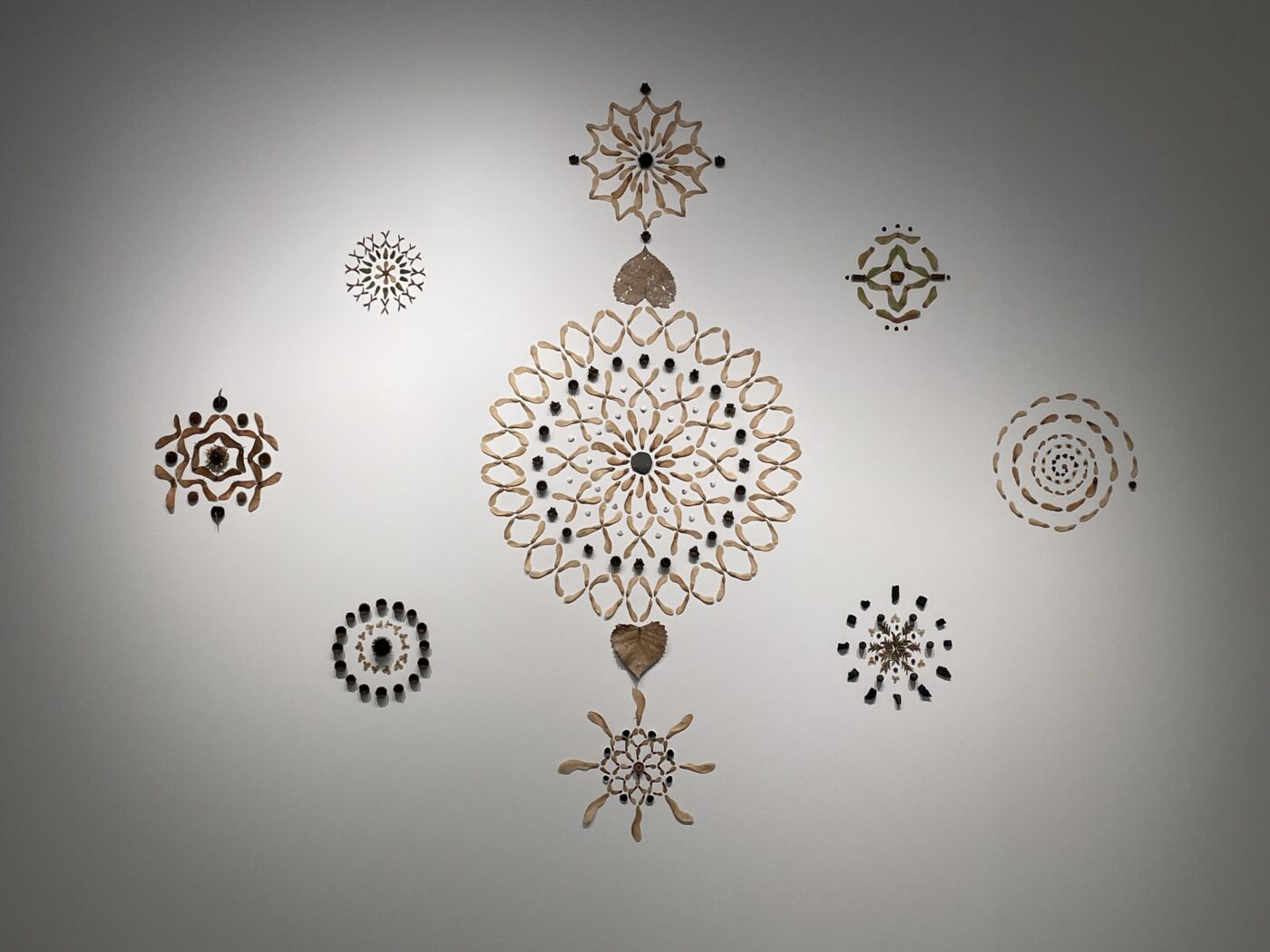

[ID: Seeds, stones, lake glass, acorn hats, and flowers are arranged in circular patterns of varying sizes. The composition consists of eight smaller circles arranged in a triangle pattern around a large, central circle, creating a larger design that is similar to a quilt pattern or constellation.]

It’s interesting too to see, in a city of this size, how green spaces are used, by whom and how the community all makes these unspoken agreements on how those spaces are used. There’s definitely lots of prairie restoration happening here. And I’m fascinated by seeing the ways in which we build our environments and then change our minds, or we build our environments and then nature has other ideas about it. Something that I find really interesting here is when you come downtown and you first get off the Blue Line and you emerge from under the ground, into the city, something I hear frequently is that everybody can sense where the lake is. And many of them sense that that area used to be a marshland simply because of how the wind still moves through the architecture of the downtown space.

I think there’s some really fascinating echoing that happens in between things that are naturally occurring and things that we’ve built and things that blur those boundaries because I really focus on prairie ecology. And the prairie ecosystem is a manmade ecosystem. It’s a built environment that was created through the repeated and intentional application of fire to land. It’s maintained because of fire, because of grazing and because of certain kinds of pollinators. And, people like to think about nature as this thing that man is so separate from, but that’s just really not the case. I mean, even in these beautiful expanses of what we think of as untouched nature, it’s not. It’s really a collaboration.

Kate: Yeah, that’s really interesting. I love what you said about being able to feel that it used to be prairie. I’m also based in Chicago, and I definitely think it’s interesting how we all orient ourselves toward the lake, and just use that sort of like a navigational system. There is just a sense of that old natural environment.

I think you touched on a question I was also going to ask. You were talking about how people make an environment or a structure and then change their minds about its future perhaps. And so I was gonna jump to my question about how you both consider ephemerality in your work, especially in relation to your point about prairie land being a built environment itself. How do you both think about the idea of the ephemeral, just sort of the future of the things that you’re making?

Selina: I think, once again, because I’m in architecture, it’s very much a heavy thing, not only the actual ecosystem of wherever it sits, if there is an ecosystem still there, but it’s also heavy on the community. And that acceptance or use of that building really impacts the future of the architecture and how it’s used. And I think that for me, as someone who has been able to see things come to life — because a lot of my work happens in the digital world to start and then can translate to reality over time from just a simple concept to, maybe like two or three years later, it actually comes into reality. And that relationship between the digital and reality is for me an interesting time because there’s so many phases of that, and none of those phases ever feel permanent until the actual start of construction or bringing something into materiality starts to occur.

As much as we can think to the past, we also have new technologies that can help even push it forward for the next generation and the legacy that it could leave for the people in the future.

I approach work by trying to achieve something that could be timeless as well as flexible to change in the future, and that isn’t necessarily based off trends. In the past when I have taught architecture studios to students, I definitely have always approached it from the lens of a bioclimatic contextual response. That means responding to climate versus just creating an architectural object. How can we create architecture that basically responds to the climate that it’s sitting in? And that also includes the resources that we’re utilizing in that architecture, so things like passive design or building for the sun; the quality of the materials utilized, even down to the plants and colors that you might integrate into the building; the orientations of windows with stars and different alignments, such as the solstice and equinoxes.

Those are all approaches to how our ancestors have built and designed in the past, but also how do we combine that with what we have access to today? Where we find the balance between the two has been a big focus for me, to find that sweet spot or hybridization. Because as much as we can think to the past, we also have new technologies that can help even push it forward for the next generation and the legacy that it could leave for the people in the future.

Lydia: Yeah, I’m also fascinated at that crossroads of digital and reality, where concept becomes an embodied practice. In my work, I’m not necessarily concerned with the object making it into the future as a material object. What I’m really more interested in going into the future is each one of those seeds, each one of those plant kin or earth kin that composes it, in highlighting them so that people care about them. So that they do make it into the future, so that we don’t forget their names, we don’t forget that they were here with us, that they’re still here with us, that we’re all here together.

I’m really interested in the ideology going into the future, it being a continuance of the things that I’ve learned from my ancestors and putting that knowledge forward as something that can continue existing in the future. Then also presenting it in a way so that it can be accessible, so that it can be not just an idea or a belief system that’s held by one culture, but something that can become part of the greater cultural thought and consideration of how we navigate the world that we’re living in. That can change the way we view our relationships with one another. That can change the way we view our relationships with our more-than-human kin, that the collective liberation includes the planet and the land. I’m fascinated by the idea of building things that don’t necessarily need to be tangible to go into the future, really holding down that part of intangible culture that goes alongside our material and tangible cultures. And that really informs them.

Something I am really in love with that I think about frequently is the structure that is in the Chaco Canyon, because it’s a structure that tells time and place just by the way it’s built, and it has existed through all of these changes. Even though the time has shifted, it’s still telling time, and I wonder what it would be like if we were living inside of structures that were always pointing us back out to the environment. I feel like I’m excited when I hear about architecture that’s really considering how we are in those spaces and how those spaces influence us, mentally, emotionally, physically, spiritually. We all do our parts, and I feel like I’m just really focused on the part that is intangible. How do we carry forward the thing that’s not tied to an object? To me, that’s through embodied practice. And so how do you get people excited to make an action? There’s an ephemerality to it in the sense of there not being an object to stand around forever, but there’s sustainability in this knowledge-passing that happens.

[ID: Selina works at a dusty building site with a child. Facing away from the camera, they mix material for brick-laying in a plastic tub.]

Kate: I really did want to talk about beyond-human or more-than-human kin as you describe it in your practice, Lydia. I wanted to hear more about how you describe that, but also from both of you, if there are beyond-human kin that you feel more drawn to collaborate with than others. Could you talk about collaborations with non-human kin or beyond-human kin and what that means to you?

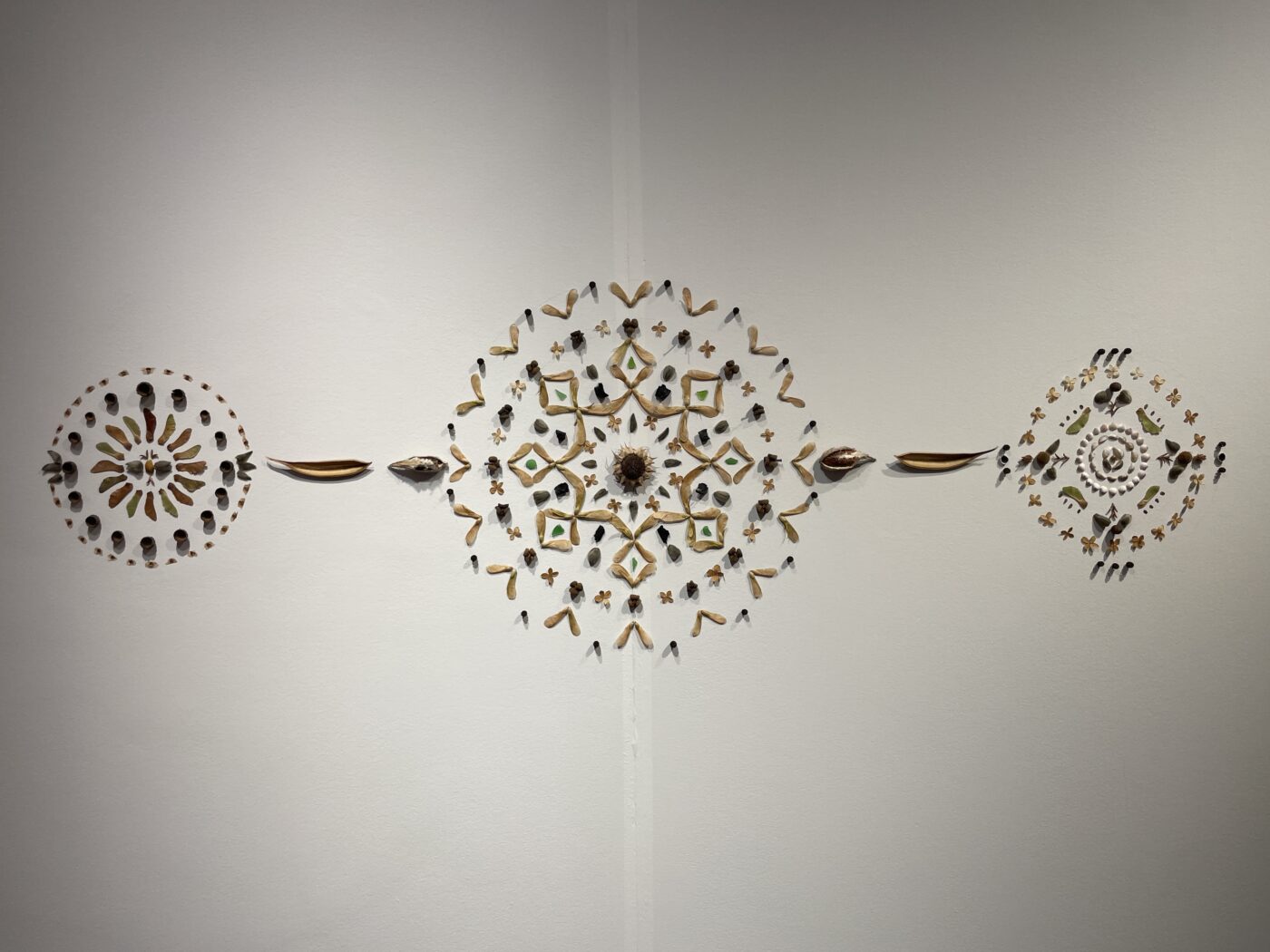

Lydia: I was raised in a cultural belief system that views all life as my relation. As such, it’s my job to treat them correctly, to treat them with respect, to understand that we’re in a balance, and to know that I’m not elevated above anything. The things that I need to eat to sustain myself eventually eat me. We’re part of a cycle. We give each other what we need, and there’s a balance to it. So when I’m talking about collaborating with my more-than-human kin or my beyond-human kin, I’m really just referring to the world, when I’m pulling in material to work with on an installation. When you’re spending that time with nature, it does become difficult to be like, oh, this is just materiality, because it’s truly not. Those are my brothers and sisters. Those are my relatives, and there’s a mindfulness to that relationship. I’ve been taught in gathering practices that there are certain ways to gather. There’s a way to go about asking. There’s listening when you’re told “no” and honoring a “no.” There’s the exchange of the gift that you’re giving in exchange for the gift you’re receiving, being mindful of, what is an abundance? What is necessary? What is the environment or ecosystem needing? During the fall season, you won’t catch me gathering acorns, because that’s not mine for that season. That is for our relatives who are getting ready for winter. It’s not for an art piece. And so I just, I think about if I’m working in a reality where everybody is my kin, if I am wanting to really bring forward that kinship pedagogy, then that means really exemplifying what to honor one another means.

And so I’m always gathering what I have the greatest relationship with, which for me, has primarily been Maple samaras, from a tree that’s actually not native to this continent. And it’s because they were the trees that grew in the yard of my childhood home. And so acknowledging that there are beings here that are present here, that got brought here, and that they’re still around me, they’re still part of that kinship that I experience. I also went through land management, and there are species that do need to be removed. I’m mindful of that, too: the balance of the ecosystems and how everybody can get along, and what those limitations are.

I’ve been taught in gathering practices that there are certain ways to gather. There’s a way to go about asking. There’s listening when you’re told “no” and honoring a “no.”

I’m really thinking about the agency of these other entities and beings, and what it means to bring them into a gallery space with me or bring them out of their space into my space, and how I host them during that time. Who wants to be next to each other in these conversations that we’re making, and why are we having this conversation? Typically, it’s because I’m trying to locate myself in a place, and I do that by locating myself amongst my kin. But part of that agency piece, part of that really honoring them as my kin, is that when an installation is done, everybody gets to go home. These are not installations that are meant to hold people hostage or put them into stasis or cover them in arsenic and keep them in the Field Museum’s basement for the next 500 years. This is really about letting people go home, letting them fulfill that duty that they have on this planet.

A seed is a seed. It’s meant to do what seeds do. So by taking them home, by really honoring them as what they are, which are their own selves, I close that circle. I keep that cycle going. I don’t hook us up anywhere and keep us in a place that’s not conducive to growth, or not conducive to renewal. When I’m thinking about those kin, I’m really thinking of them as my relatives.

Kate: Does that resonate with you, Selina?

Selina: Yeah, definitely. Similarly, I think that, in this time, [laughter], the majority of the population typically sees themselves as above the species that surround us, both flora and fauna, and even above the ecosystem as a whole. That creates this idea that we are dominating nature when in reality it should be more from a place of mutual respect. And because of the lack of relationship, especially living in these urban environments, even though it’s still present, both seasonally and through the cycles that come with that, there’s just a big disconnect for a majority of the population.

One of the projects that I just created a digital exhibition about focuses on the connection between what we can consider cultural keystone species, species that are significant to a culture, and how those are influenced in the outcome of what could be considered our material culture. For example, it could be our food, our medicines, it could be references in stories and songs, it could be architecture, the things that we wear. It could be our instruments, all of those things. I say this from the perspective of my own culture, that a lot of the materiality that is utilized in those items or in those designs is being derived and resourced from an ecosystem. My tribe is along the Rio Yaqui in Sonora Mexico, and all of the things that we see within our regalia and these design outputs of our culture are all derived from that ecosystem.

[ID: Seeds, stones, lake glass, acorn hats, and flowers arranged on a white wall in two small circles framing a larger one in the center.]

Whatever we’re making is gonna return to this world either as a medicine or as a poison, and you get to choose which one you’re doing.

It’s such a beautiful thing that it was the inspiration for our culture. It’s cool that it has such a heavy influence and integration into what we still continue to do today culturally. But the ecosystem that those materials are accessed from is now [disrupted]. I think it’s more prevalent in desert ecosystems that we see the dramatic escalation or reduction specifically of water sources and how just putting a city next to those traditional homelands can basically remove the water that was flowing through the river. They’ll put a dam upstream and then take that water into the adjacent city. But that has a huge impact on access and to the growth and the sustainment of a lot of the species that we’ve used historically and continue to use into the future for all of these aspects of our culture. There really is a huge ecological impact when it comes to the way that our Indigenous traditional knowledge gets impacted by these bigger systems at play. That’s how we collaborate with our context. That’s how we’re in relationship to our context.

I think that for us, our emergence story literally speaks to that and also recognizes the outside forces that would come as well. In our emergence story, there’s a prophecy tree that basically tells us, if you come into this world and become Yoeme, which is a Yaqui person, then all of these other forces will come.

It also speaks of the specific seeds and foods we would eat, and, if we chose not to, we would turn into different insects, birds, water, sea animals, mountain animals, all of them. Those are basically our relatives, similarly to what she was mentioning. There’s so many different references to it, it’s really hard to ignore that connection for many Indigenous populations because of that ancestral connection to our ecosystem. I’ve seen that not just me as an individual, but my community ancestrally has been collaborating with our ecosystem since the beginning, and we see that prevalent through the design output of our culture.

I’ve seen that not just me as an individual, but my community ancestrally has been collaborating with our ecosystem since the beginning, and we see that prevalent through the design output of our culture.

Kate: To close out the conversation when we have just a few more minutes left, I’ll circle back to the beginning a little bit to ask: what are the learnings, from your cultures, also from your practices, that you lean on most heavily? What’s most urgent for creating a better world? What do we as a culture need to learn to take better care of our world? Lydia was talking about potentially going back to go forward. What are those items that we need to carry forward with us?

Lydia: I think we need to learn a greater love for our intergenerational selves, so greater love for our children, and greater love for our elders, and greater love for ourselves. Also: learning that whatever we’re making is gonna return to this world either as a medicine or as a poison, and you get to choose which one you’re doing. And I say that knowing that we live in a society where many of us have been forced into poverty or forced into situations like how my family is located in Oklahoma, the aquifer’s been poisoned, and people have to drink out of water bottles. While understanding the realities of what oppressive regimes do and what disenfranchisement over thousands of years looks like, I think it’s just good to know that we do get to choose, especially as artists and as creators, that we can still make within our ethos, that we can still make with these values in mind.

We can look toward the future while holding the past but not needing the future to be the past. I feel like the Western world’s so obsessed with immortality and I just really wanna let them know that it’s okay to die. We’re all going to do it [laughter]. Sometimes it can be really beautiful, like if you have ceremony and culture around you, if you have these pathways, it’s okay to let your legacy be good teachings and good actions as opposed to like, there’s a bronze sculpture of me that’s going to sit in this harbor forever now [laughter].

[ID: Two women walk through the rubble of an abandoned building with no roof, empty windows, and one wall missing. They are framed in front of tall bushes which are growing in the center of the structure.]

Selina: Yeah, that’s true. I also think about my work a lot from the past, present, future methodology, and how we can consider the past, but also know that we have to pave new ways for the future. What I create, I want to be relatable to the next generations. That’s really critical. Especially in the time of iPhones and iPads and short attention spans, you really have to grab their attention in a way that meets them where they are, for all generations, to create and establish some sort of intrigue or relationship that is attractive to them, especially when it comes to cultural preservation. I think that’s one of the hardest things to gear toward that next generation because the ways that we’re trying to teach that information are very dull to that next generation. Trying to find new methods or means for that approach can really help that preservation of these languages or traditional ways of doing things and creating hands-on opportunities — those all help stick with them, versus it just being a research paper or a book that doesn’t actually bring value as far as creating a memory for people. The work that I do with community is really focusing on relationship building and creating that connection that goes beyond an in-and-out scenario where I’m just like, oh, I’m here to extract something from you because I feel like that’s what we often do in this role.

I’m interested in what you’re doing, and then there’s a mutual understanding and relationship that can be built more long-term for the benefit of both of us and for the community. So I think those are the things that I would say are the simplest way to approach and to navigate from non-ego. I don’t claim to be the expert in my culture. I don’t claim to be the expert in my own profession or in the things that I do. I’m just trying to create things that benefit us. And, I might not always get it right the first time, but I think that’s when that relationship comes into play and how you are able to get that feedback loop to continue to build something better together. Those are the simple things that people tend to overlook: the importance of our relationship to each other.

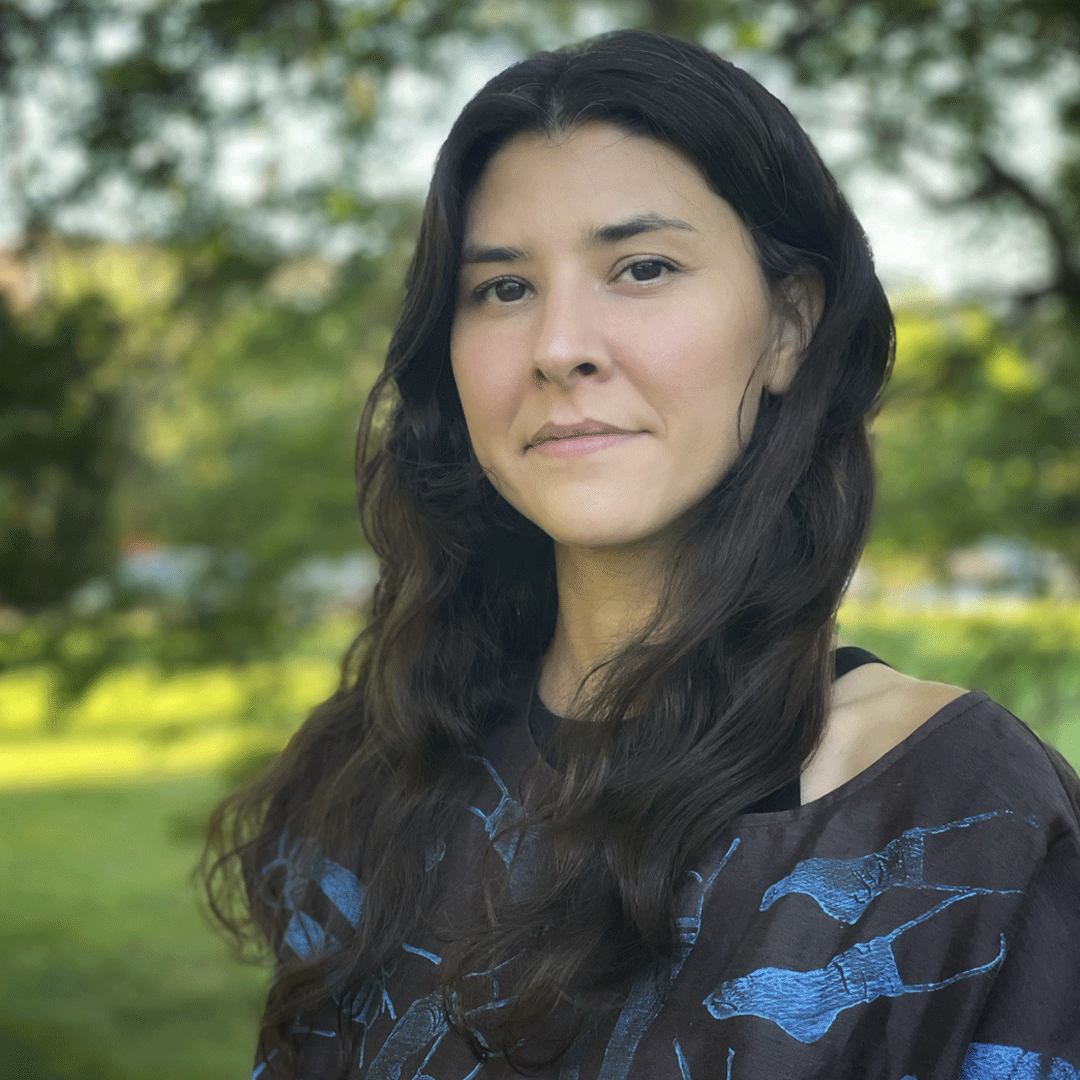

[ID: A woman with long dark hair gazes at the camera. She wears a dark blue-patterned shirt and stands against a blurred, natural background.]

Lydia Cheshewalla

She // We

Chicago, IL

Lydia Cheshewalla (Osage/Cherokee/Dakota/Modoc/Xicanx) is an ephemeral artist from Oklahoma, living and working in motion throughout the Great Plains ecoregion. Through the creation of site-specific land art and ephemeral installations grounded in Indigenous land stewardship practices and kinship pedagogies, Cheshewalla engages in multivocal conversations about place and relationship. By working within a framework of change and collaborating with beyond-human kin, she rejects capitalist reliance on scarcity, immortality, preciousness, and waste production in the creation of value and remains responsive (responsible) to the realities of shifting ecologies in an age of climate crisis. Her work has been shown at Amplify Art’s Generator Space, the Union for Contemporary Art, Comfort Station, Harold Washington Library, EXPO Chicago, and the Center for Native Futures among others. She was awarded a 2020 Tallgrass Artist Residency, participated in the 2022/23 Chicago Art Department Think Tank: On Mending, and was a 2024 Spring Tanda Fellow through Chuquimarca Projects in Chicago. Cheshewalla is filling the bucket with water to see if it leaks and is often found standing in fields.

www.lydia-cheshewalla.com

Instagram: @goodwithcoffee

[ID: A woman of Mexican descent is photographed from her left profile. She smiles and is dressed in a dark gray sleeveless dress as she looks over her left shoulder at the camera. Her long black hair falls straight behind her left ear that is adorned in multiple gold earrings.]

Selina Martinez

She // Her // Hers

Pénjamo – Scottsdale, AZ

Selina Martinez is a member of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe and Xicana born and raised in Phoenix, Arizona. She is currently an architect-in-training pursuing her architectural license. In 2020, she was a recipient of the Radical Imagination grant from the NDN Collective, establishing the seed funding to create Juebenaria, a project focused on providing an evolving collection of a plurality of Yaqui lived experiences through digital media. In 2022, she led architecture studios at the Design School at Arizona State University, integrating the use of 3D laser scanning and Indigenous/bioclimatic desert design responses. She is a 2024 USA Fellow in Architecture & Design. Martinez is also the co-founder and lead instructor for Design Empowerment Phoenix, a program of the Sagrado Galleria in South Phoenix, that creates opportunities for the community to engage in design tools and processes.

https://www.selinamartinez.com

Instagram: @kaajoame