“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” —Octavia Butler

25–30 minute experience, or the time it takes for a midday stretch.

In their conversation, Amos Paul Kennedy Jr. and Leslie Diuguid express the values they share as printers: community collaboration, caring for the matrix, and the print shop. They create an engaging dialogue centered around the democratization of printmaking and invite readers to ponder the interconnectedness of sampling. Kennedy offers a fresh perspective on the notion of dissection in Western civilization and argues for the inherent influence of existing sources on contemporary creations. Diuguid demystifies her process of amplifying artworks, highlighting the microscopic and expansive changes that occur in the transition from individual pieces to multiples. Discover how they, as artists, draw inspiration from their surroundings, shape their craft, and share their creations with the public.

BY LESLIE DIUGUID AND AMOS PAUL KENNEDY JR.

[ID: Du-Good Press logo triumphantly displayed on the glass door of its new location in Bedstuy.]

Luz Maria Orozco: So I wanted to start off with Leslie: in our emails, you mentioned a bit about your thoughts on this idea of sampling and what it means to you. You were using words like dissecting and recreating. And so, [I’d love for you] to share more about that, and if you had a specific example or a project where you were dissecting and recreating elements for a collaborative edition with an artist, if that process contributed to achieving a desired artistic vision, and if there were any challenges or opportunities that it presented?

Leslie Diuguid: Yeah. Challenge is a better word than struggle. [LAUGHS] I’m constantly starting new things and finishing others, and printing takes two seconds. It doesn’t take that long to actually do the printing part. So a lot of what I do is hyping myself up to then dive in and really do the dissection work of not necessarily recreating artworks because it’s amplified. I’m making something that is an individual piece into multiples. And that translation — microscopic and expansive — changes things.

When diving into one color at a time when I have an original work of art and have to make multiples of it, it has to be enhanced in certain ways, and that is a sampling process. I can take different elements, and I can make them bolder. I can make them cover different areas, and then cover that up in different spots so that the — one color at a time screen printing thing — can actually make it more depth-oriented than what it originally ends up as, a painting on a surface.

So, I just finished a piece by Pope.L, and this is for 52 Walker. This is supposed to be released today actually. It’s a washcloth and a piece that was three-dimensional but now is on paper. The way that I’ve dissected it really has to do a lot with the mastering. And it’s different than mastering a language or a technique, it’s mastering in terms of music production. I think of it as taking different levels, changing their frequency. Purple gets in the way of green, the green goes down first, so really that one gets out of the way of everything else.

[ID: Leslie is holding an X-Acto knife, making the final cut to Pope.L’s edition. The artwork is a colorful array of paint and scribbling on top of a green washcloth.]

I have to think in terms of forwards and backwards so that I can lay out all the colors, and then adjust them as I go. It’s different from what can actually be printed because some things are not individually separable from their background, and that has to be distinguished in ways that I can’t quite describe. I have to over-cover stuff, and then under-cover it, and bring it back out.

The edition I’m working on now is Na’ye Perez. It’s too wide for me to print all at once, so I’m ending up printing it in a right half and a left half. That final touch of tweaking things goes back and forth to make one side finished and the other one not. It’s a process of sampling.

I’m taking different spots from this, but I’m enhancing them and pushing them back and adding different elements that weren’t there to begin with so that it can jump off the page in a way that the original did. I’m not looking at it [in person], I’m just looking at files mostly. I can see that it could be more dimensional, and I have to push and pull that in different ways so that the texture that is there feels very three-dimensional even though it’s super flat.

That’s the part with multiples that I think is pretty magical. You can take one piece and distribute the wealth and make it so lots of people can own that type of satisfaction. It doesn’t have to be visited in a museum. You don’t have to go into a different space to get that quality that the artist was trying to convey in their piece. And that’s what I like about printmaking: you can satisfy that bigger mass.

That’s the part with multiples that I think is pretty magical. You can take one piece and distribute the wealth and make it so lots of people can own that type of satisfaction.

Like music — where instead of being in a live performance, you can listen to Spotify — I feel like I’m doing the work of someone who’s usually in an audio recording engineering room. There’s a lot of engineering that goes into this. I hope that it’s translatable in visual terms, too. That frequency shift is, really, the work of a printmaker to translate things. I don’t know if that makes sense for sampling, but that’s how I see it.

Luz: Thank you so much for all those thoughts, that was great. Thank you for showing all of those pieces.

Leslie: Those are just the two I’ve just worked on right now. And, I’m still in my bedroom. It’s crazy frustrating to have all this new space to get into, but, really, I need to finish my washout booth. That’s the only thing left. I got all the machines in there. I got my big exposure unit ready to go. It’s the washout booth that needs to get done; the skeleton is done. I’m trying to make a good filtration system so that I don’t pollute the world. It’s bootleg, but it’ll function. I just have to put all the pieces together.

Amos Paul Kennedy Jr: Therein lies one of the problems that people don’t realize: there’s this whole other layer of making stuff that you have to consider. I’m assuming that you do not have the funds just to go out and hire someone to bring in a filtration system, so you had to go learn about it. And you had to learn, well, how can I put one together?

Leslie: Yep. I think it’s $1,200 to buy it, but I figured it out for $500. I had to visit a lot of friends, and see their shops, and see the better ways of doing it. I worked in a lot of other shops, so I know that you have to do something or face the consequences of build-up all the time, and that’s no fun to deal with. I’d rather get started out on a better foot. I have to stay here to finish these complicated jobs that I have to do in halves instead of all at once because I can’t print bigger yet. It’s frustrating to not be there yet. I could just stop printing for a while, put on my fundraising hat, and try harder to get people to give me money. Which they would. It happened years ago, when I used to have a GoFundMe for a space that fell through.

But I never got to the point of getting enough funds to secure an easy move. So I’ve

been working through this move so that I didn’t have to stop. I have to keep making money now at this point, I have to keep paying for it. I don’t have any more build-out time to float for this, but that’s how it is.

Did you find that when you were interested in printmaking, the excitement of making a print is fun, but the setup is a whole different hat to wear than the appreciation of just art as is?

Amos: When you say setup, do you mean the setup to do the actual printing or the setup of the shop?

Leslie: Yeah. I see them as hand-in-hand, chicken and egg. You have to have the shop set up for you to do the setup of the print, and then get to the magical end of having a print done.

The space is important for me as much as any of the tools or any of the equipment that I have in that space. You have to be able to float through it, in order to flow through it.

Amos: I look at the shop as just another tool in printmaking. For lack of a better term, it is the great big toolkit that you then pull from the parts. The establishment of a shop that you feel comfortable to work in, is extremely important in order for you to do the best work that you possibly can.

I spend a lot of time walking through [the shop] and trying to figure out: where is the best place for this tool to be in order for me to minimize the trauma on my body to get to it? Once that is done, then I can actually begin to make things. But I can’t accomplish the task of finding the best space for each of the tools in my shop unless I’m actually using them.

It’s through its use that the shop evolves into this space that I’m very comfortable working with. That allows me a freedom to make [prints] that I couldn’t do if I felt a little more uncomfortable. The space is important for me as much as any of the tools or any of the equipment that I have in that space. You have to be able to float through it, in order to flow through it.

And that’s one thing a lot of people do over time.They give a lot of consideration, especially when you move in. What’s the square footage of this press? Where can I put it? When I start to use it, how am I using these tools? Where can I find them? How can I get to them easily? That becomes a big issue for me.

Leslie: Yeah, accessibility is really important for a shop to be functional. You have to really make it so you’re not going to trip over everything and Steve Urkel the whole operation down, too, right?

Amos: Right.

Leslie: This small space that I’m in is highly functional, but it takes constant maintenance. Just sweeping up this morning, and finding all kinds of funny trash that I just dropped yesterday. But I have to do this every day because I’m barefoot, otherwise, it’s this soft floor.

Amos: People tend to overlook or minimize the maintenance that is required: not only taking care of the shop, but taking care of the equipment, taking care of your tools, taking care of the supplies you have. These are just as important as the actual act of printing. These are the things that allow you to have that act of printing, so you should celebrate and do these things. As you said, sweeping the floor. Now, that should become a ritual as much as you are standing at the press getting things organized so you can make that print. You should give as much attention to that as you give to anything in your shop.

Again, we have a tendency to dissect the world and not look at it as it is, just one big wholeness. The way that I look at the world is just as one. There are no separations; the separations do very little to improve the world. So if I do not celebrate one part of my life as much as I celebrate the other, the fulfillments of my life is not complete. I have to celebrate it all to the maximum. Everything is just as important as anything in my life. And my life is important because it is. The time that I spend sweeping my shop is still my time, and it is important. So I must celebrate it and revere it, as much as I revere pulling a print or pulling a poster.

Luz: It’s so important to put that love and care into that space and see it being translated when people go into your shop or people see your prints. That really resonates with me a lot, so thank you for sharing that.

On that topic of putting that intention into your space and into your practice, Amos, what do you think about the idea of taking snippets from existing sources to communicate your intended meaning in your prints? And if that translates into your shop and your broader practice, too?

Amos: Well, one of the issues that I have is that Western civilization loves to dissect everything. When I was a very young man I said that Western civilization will kill the last tree to try to understand it, rather than allowing the trees to exist and understanding them [as they live]. We feel that by destroying, by minimizing things, our knowledge will grow. And so this idea of sampling, if you take a look at the way that I have seen the world, civilization and knowledge has changed, or if you want to call it, “progressed.”. It is only because it is built upon what has already existed. Those things that have already existed inform the things that I create now.

Who doesn’t sample? No one spontaneously creates something new. It is all built upon the work of our ancestors, and it will be altered and changed by the work of our descendants.

So, am I sampling or am I simply doing what is natural? Am I evolving all these things that exist? You say, well, you pull something from here and you pull something from there. But isn’t that the way that it’s always been done? Oh, but if we call it sampling, we have a better understanding of it. Sometimes you do need to understand things [upfront], but at other times you need to do things and understanding will come.

I come from a school of thought that theory comes from practice, practice doesn’t come from theory. By doing, you begin to understand more. Do I sample? I guess I do. I am influenced by the world I live in, and I cannot deny that influence upon me.

There are those people that can look at my work and give you a better analytical understanding of it than I will ever be able to do because that is not my concern. My concern is simply to make stuff, to put ink on paper. Then, to share it with as many people as possible.

One of the things that printing does, it allows for the democratization of things. It allows for us to make things happen and then share it. I believe that this is one of the reasons people choose printing as their medium. Because they have ideas, they have images that they want to share, that they want out there in the world. This idea of sampling is just a part of living.

But what we want to do is say, “Oh, it’s special. We are sampling.” Who doesn’t sample? No one spontaneously creates something new. It is all built upon the work of our ancestors, and it will be altered and changed by the work of our descendants.

Leslie: That’s a great way to put it. Yeah, it’s like a mic drop.

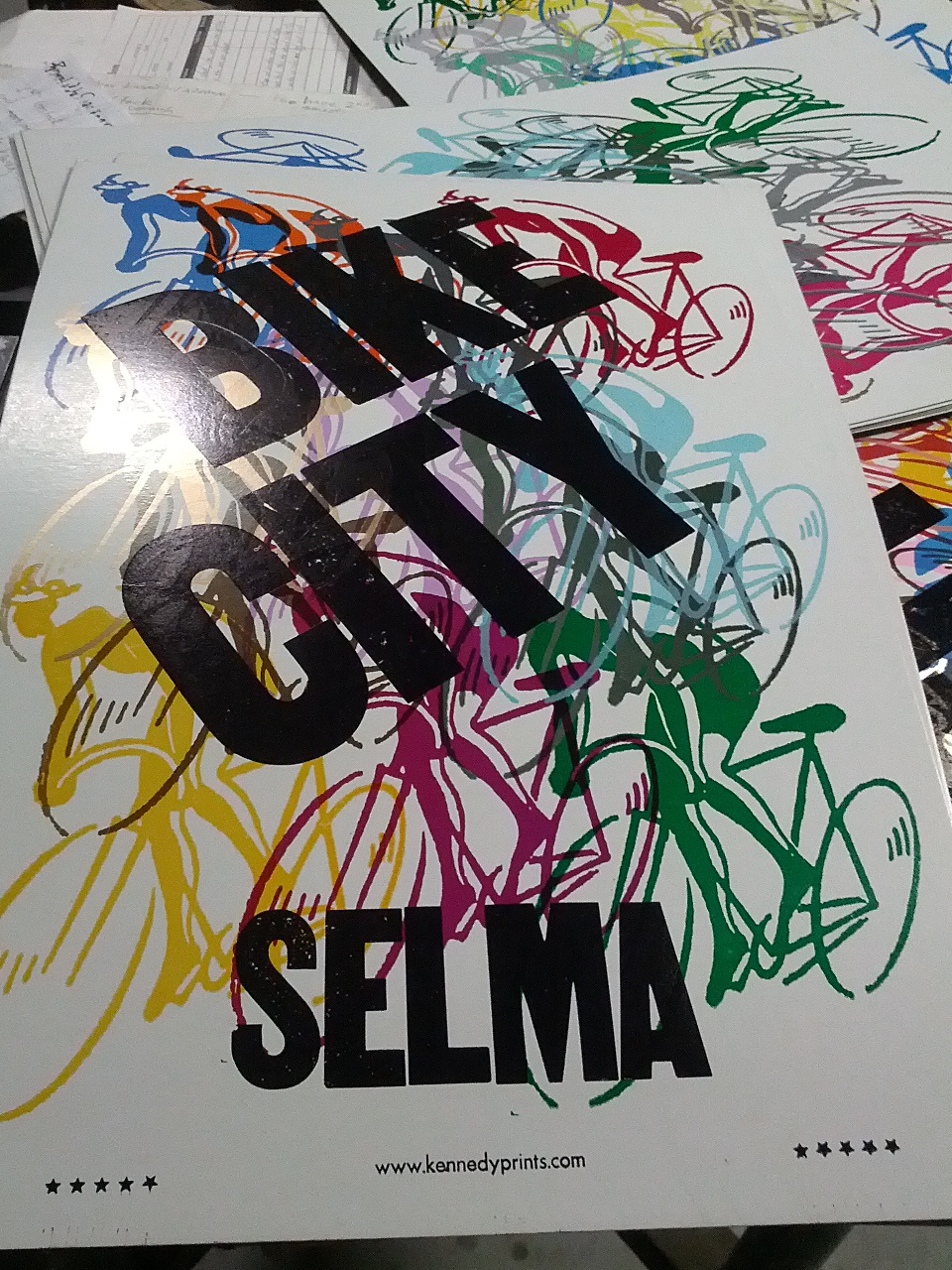

[ID: A letterpress print with bold black text of “Bike City Selma” is layered on top of colorful graphics of cyclists. Bottom text reads “www.kennedyprints.com,” surrounded by small black stars.]

Luz: Thank you for sharing that; everything is very interconnected. That’s the way that sampling or being inspired by other things is a beautiful process. To see the history or trajectory of things is really important. Leslie also talked about democratization and being able to create multiples, to not have to bring people into other spaces just to see the work. And I wonder if there’s something there to talk about.

Once I was asked if I was in special collections and museums, and I said, “I’m in a few. But more importantly, my work is in more than 5,000 houses around the United States.”

Amos: About five or six years ago, I made a conscious decision to minimize the number of exhibitions I have in galleries and museums unless those galleries and museums made a commitment to me to go out and interact with the surrounding communities. And that interaction was not just to invite them to come see my exhibition, but to go out and obtain quotes and sayings from those communities, and to identify institutions within those communities that could have a mini exhibition of my work.

Those institutions that you speak about people coming in to see the work of printers and printmakers, those institutions have traditionally excluded my people, poor people, from attending. Maybe not overtly, but inadvertently, through the atmosphere they create, which is not welcoming to poor people. So I said, “You have to go out to the masses and tell them that we welcome you.” To show that we welcome you, we come and pay honor to you, in the places where you exist. This is one of the things that institutions will have to do if they want to survive. The way that this civilization is going, there will soon be far more poor people. Well, more than there are right now. Far more poor people than the wealthy people that have maintained the museums and the gallery spaces that so many people clamor to be a part of. What I want to do is make work for the people.

Once I was asked if I was in special collections and museums, and I said, “I’m in a few. But more importantly, my work is in more than 5,000 houses around the United States.”

Leslie: Isn’t that amazing? Yes.

Amos: There’s not many people that can say that.

Leslie: No, that’s incredible.

Amos: And that’s far more important. Because those people see my work every day. Everyone who comes to visit their house will see my work. I would rather have my work in 5,000 or 15,000 homes around the United States, than in the top ten museums. Let’s face it, as someone who makes two-dimensional work, it is probably going to end up in offsite storage in flat files that may be brought out once every ten years to be exhibited. It’s not going to be on the wall every day for all the people walking through that museum or that gallery to see.

Leslie: That’s a really good point. It’s impressive that you handled each one of those prints that did end up in the homes of 5,000 different people. It’s not like you hit the print button, and there’s a bunch of distributors, and it’s gone. I totally feel a lot more connection to the people who bought prints off my website, and then have them in their home. Then I lose track of like, what institutions have this one? It’s findable. I could figure it out. But it’s minimal to me knowing that there are people that have these things and don’t have to go to the institutions to really view them. I think that is the democratization element that’s really impressive.

Luz: Thank you for sharing. One last question I have is about the repeatable matrix in print, and how that could be perceived as the motherboard for sampling, and how often it stands in juxtaposition with “unique artwork.” If you all have any thoughts about what is your relationship to the unique versus the multiple, or if those aren’t even in opposition at all.

Leslie: I think the matrix is something that’s not done yet. It’s a part of the final product, but it’s not made to be the form. It doesn’t take on that body because it’s just used to be a tool, still. All the films I’ve got laid out all over the place, I have to keep them very precious for my purposes. Like Amos was saying about the practice of maintaining your space, and all the little things that go into making the print happen, I could never outsource that to be someone else’s job. I have to maintain and create these things as the practice to get to the printing part. If I don’t do that small step of even caring for the matrix, then I’ll lose track of what’s necessary when I’m on press with the screen that somebody else could have made. It’s harder for me to take that precious element as something to be cared for, and maintained well, if it’s not in my hands and in my control.

That’s part of the tactile element; valuing that individual matrix that I’ve found and selected. It just takes a lot more care to get to that point and then use it in the way that I’ve manipulated things to work for. The matrix is what makes everything possible, so that’s the egg — it’s not the chicken, it’s just the fun part to come.

[ID: Black and white image of Leslie’s right hand in a fist, holding pliers to untwist the stripped metal hinge clamp that holds the screen in place with shims on her press.]

Amos: Multiples and unique. What isn’t unique? Even when you make a multiple, when you make the first one, it redefines you before you make the second one. So the person who makes the second multiple is not the same person who made the first multiple. And the uniqueness in that moment, in that nanosecond, changes the first from the second. When we think of multiples, most people will think of repetition, the sameness to each one. But nothing is the same that is made. Everyone is different and unique. We must recognize that uniqueness. We must recognize that that is one of the essences of life.

For me, I see no multiples. I just see people making things. I see no necessity for uniqueness because everything is unique. So, why try to separate it? I believe that [separation] is part of the overall capitalistic view of the world. If I can make things unique, if I can make things scarce, then I can make the one thing that means absolutely nothing: money.

So we go for, “Oh, let it be unique.” How can you do 100 prints and have each one be unique? How can there be a billion stars and each star is unique? How can there be trillions of leaves and each leaf is unique, each flower is unique? Why is it that I want to deny what is so natural by making something that is supposed to be repeated? Why is it that I want to say that there is something called multiple repetition that is different from uniqueness? I am unique, therefore, all that I make is unique whenever I make it.

Leslie: What about the setup involved that allows you to recreate things over and over, the machines, the elements that give you that capacity to recreate things?

I think the matrix is something that’s not done yet. It’s a part of the final product, but it’s not made to be the form. It doesn’t take on that body because it’s just used to be a tool, still.

Amos: Do I recreate things, or do I create new things? Again, the person that I was two years ago when I created this image is not the person today that is creating this image. So I have changed. I will change things in the middle of a [print] run, because I can do that. For no other reason than I can do that, and I feel like doing it right now. I just love this ability to make multiples and to celebrate a multiple by making each one of them a little bit different. Because they are different, and as I said, because I’m different. For lack of a better term, we use this term “art” in this civilization that a lot of people have a great misconception of, but it’s a universal misconception.

Art is actually the transformation that one goes through to bring an image in their head to the physical world. It is the transformation that you go through to make that happen. And that is unique every time you do it. You cannot get procedures to do it. It is [art], for me, that happens when it is supposed to happen. It is the doing that makes it done. It is not the planning. It is not the strategy. It is the actual act. And in the act, I am transformed by the act as much as the act is transformed by me. This is what happens when there’s no one in the shop but you, and there’s plenty of press.

Leslie: You come up with all these cool thoughts, and then you can have more things to put on prints. It sounds like a good spiral to be in. I love that.

Luz: Thank you both so much. This feels like a good place to wrap up unless there are any other lingering thoughts or questions you both want to ask each other.

Leslie: I like that element you were mentioning of holding your own history. Everything that you make is impressed upon you, and everything’s the same or vice versa. It’s a really rich thought.

Amos: Thank you. I think that as you go through making things, these ideas come. Why am I making it? What’s going to become of it? But more importantly, how is it really transforming me? Because it transforms me. It transforms the world I’m in. Will it transform other people who experience it? I think that’s what you want [the viewer] to experience. The joy that accompanied the making of the object. Not the object, but that energy that you infused into the object.

Leslie: That’s the goal.

Amos: Yes.

[ID: Black and white portrait of Leslie holding back a smile while wearing a clear plastic tarp, hoop earrings, and a denim jacket in the rain.]

Leslie Diuguid

She // Her // Hers

Brooklyn, NY

Leslie Diuguid founded Du-Good Press in 2017 as a studio to practice the art of fine art screen printing with up and coming artists. The results are works of art that connect art, industry, and commerce.

du-goodpress.com

Instagram: @dugoodpress, @little_mouse_diuguid

[ID: Amos is hunched over the letterpress machine, concentrating on inking metal type in red ink. Amos is wearing blue overalls and a pink button up, Amos’ hair is speckled with white.]

Amos Paul Kennedy Jr.

We // Our

Detroit, MI

I am a humble negro printer.

Instagram: @kennedyprints