“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” —Octavia Butler

25-30 minute conversation, or the time it takes to look through old family photos.

![]()

A CONVERSATION WITH KRISSY BERGMARK AND NAOMI GEENA NAKANISHI

The close ties between a musician’s body and instrument mean that deep anxieties often manifest themselves in practice, both individually and in group sessions. Krissy Bergmark, a tabla player, and Naomi Nakanishi, a pianist, discuss how to create an affirming and sustainable practice routine that supports the whole emotional and physical self. Bergmark and Nakanishi address how to navigate these internal and external environments to create safe spaces where everyone can show up freely as themselves and creativity can flourish.

I had to redefine what a routine looks like for me, and sometimes that included not touching my instrument for a second.

Kate Blair: Let me just jump in with this first question, which I’m really excited to talk to both of you about. When we were talking earlier, I really liked the way Krissy referred to this as music school baggage, these ingrained mindsets and habits that you get from school that don’t necessarily serve you once you’re out of it.

Naomi Geena Nakanishi: I feel like the experience is really different for everybody, but also kind of the same. There’s a period where you get out of school, and then you’re like, okay, what are the next steps? How do I become a musician again? Which is kind of a weird question to ask because you’re going to school for music, and it just becomes your identity. But when you’re in music school, routines also become a part of your identity. And maybe that routine is not so healthy. I had to redefine what a routine looks like for me, and sometimes that included not touching my instrument for a second.

I think it’s because when I was in music school, I developed a lot of unhealthy habits that revolved around excessive practicing. As a result, I did get injured. I had tendonitis for a long time, and also had to reevaluate how to play the piano, which is really odd to say, for someone that’s played piano for over fifteen years. It’s just reconstructing my idea of being a musician, and not just being a musician, of being a person and seeing how I can fit into a community that I’m being intentional about joining.

Krissy Bergmark: I went through a lot of the same things when I got out of school, too. I realized that I had also been doing a lot of practice for other people or for ensembles. Even after I got out of school, when I would study or go to lessons or go to a rehearsal, I felt like I was constantly putting myself in the place of having to show up or do things for other people. And it gave me this lack of ownership over my own music and artistry. I realized that I was having this issue with practice, and it was just something I was wrestling with all the time. And so I started practicing, just touching my instrument every day. And I did this for a full year, initially, and then I think I gave myself a little bit of a break. This is more about me connecting spiritually with the music that I’m playing and the instrument that’s important to me and really wanting to take ownership over that for myself. And then I dove into The Artist’s Way in 2017. It was a life-changing book for me. The process of going through some of those exercises and conversations with myself was really, really powerful.

I love talking about practice — with other artists, especially — but I also ran a couple intentional practice workshops online for anybody making anything, because even outside of music school, this exists in people who are wanting to pick up piano, ukulele, guitar, or any instrument that they’re just playing for fun. Some of those ideas about not being “good” just because you don’t get something right away are societally present and perpetuated. A lot of times people just don’t really know how to practice and aren’t introduced to that in a healthy way.

[ID: Naomi takes a selfie in the ring mirror that sits on their desk between two windows. An electronic device and a container filled with writing utensils also sit atop the desk.]

Kate: What do you think healthy practice looks like? I’m also curious about what these intentional practice workshops were like, if you could talk a little more about that.

Krissy: When there is too much pressure and expectation and just the wrong feelings and ideas present, it’s really hard to invite curiosity in. I have some of my best practice sessions — and by best practice session, I mean, feeling like I discovered something, I accomplished something that felt good, I enjoyed my time, that’s important too — I think curiosity is always present when that happens.

In these workshops, I use different ways. There was one that I did that was about getting started. I draw from The Artist’s Way, and I’ve read Effortless Mastery, and Atomic Habits, and Big Magic and a lot of these creative practice books. There’s a lot out there and a lot to pull from all of them. If I don’t practice for a little while, it always feels more intimidating to step back in because it’s this weird pressure that I don’t think is ever going to go away. But when you look at practice, you’re coming to your instrument or your voice or whatever your practice is, and facing your inadequacies, because that’s what we’re doing. If it’s a composition session, that’s a different challenge. But in terms of practice, whatever that art practice is, it can be really intimidating to get comfortable with the things that you’re not yet great at.

I used to do these meditative stretches for a really long time. That was my body begging me to change the way I viewed practicing or music. I’ll probably keep that, too.

Naomi: I like that you use the word “intimidating,” because I think that perfectly sums up the feeling of coming back to your instrument after being away for so long and also facing your inadequacies. That’s why practicing has been really difficult to come back to, because in music school, practicing was always surrounded with negative feelings. If I were to start a new practice today, I would probably implement some sort of journaling. It’s kind of a nice break, or something that could feel a little bit more cathartic if you’re coming back to your instrument, and can feel kind of scary. You don’t want to sit with those scary feelings the entire time. But I think that’s really important, too, adding some sort of creative part of your practice routine. And that can look very different for other people. I used to do these meditative stretches for a really long time. That was my body begging me to change the way I viewed practicing or music. I’ll probably keep that, too.

Krissy: The way that you were talking about that was really beautiful, just being in touch with your body and being in touch with yourself and what your body is asking you to do. Something that has felt really good to me as I’ve gone through this whole restructuring process is — the first thing I do when I sit down is just improvise a little bit. Lightly, nothing too crazy, but just playing a little bit and getting in touch with how my body is feeling, how my instrument is feeling that day, because the skin heads change a lot, day to day. And kind of just knowing what I can expect of myself during that session, because I’m in touch with how I’m feeling, and how my body’s feeling, and how my instrument is feeling, and what kind of thoughts are going on in my head. Then I know if I need to expect less of myself that day, or if I’m feeling really good, and I can just dive right in.

There’s something about that improvisation practice that solidifies my own personal voice on the instrument. This is nobody else’s time but mine; this is nobody else’s space but mine. It’s just me and this instrument, which I feel like has given so much to me, in terms of, this is an instrument that I really found my voice and an expressive capacity on. There’s definitely a lot of gratitude in that too. There’s nothing else, none of this other stuff matters, it’s just me and this instrument, sitting down to do our thing together.

[ID: A close-up of the skinhead of a tabla framed in front of a table with an ornately carved box and candles.]

Kate: We’ve been circling around this question, this topic of curiosity- versus fear-based relationship with your instrument. Naomi, I was curious how you turned that around. How did you change that relationship with practice to curiosity, rather than fear?

Naomi: It’s really interesting how the human mind can manifest these feelings. I first discovered this was happening when I took a lesson with this amazing pianist Shai Maestro. He used to practice ten hours a day, but that wasn’t healthy for him physically and mentally. And I asked, “Why mentally? Physically I can understand, but mentally — you’re so focused, and inspired, and determined when you’re practicing. How could it affect you mentally?” And he said, “I just started to have bad feelings when I came to the piano and feelings of resentment.”

And to me, it was like, wow, I didn’t even know I could have feelings of resentment. Or I didn’t really know that that’s what it was. Because I also have bad feelings when I sit down at the piano. There are days where I just absolutely hate the instrument, when I sit down, I just know, already, this practice session is going to be bad.

The way he changed it around was that, if he had bad feelings, or he knew that he was going to sit at the piano and feel anger and sadness towards the piano, he just didn’t practice that day. And it was really hard for him because he was used to following through and pushing through, and practicing no matter what. I think that’s a very common musician thing. But he said, “I really made it a point to be at my instrument with feelings of joy, of being inspired and thankful.”

So that’s what I started to do. As a result, it looked like me breaking my routine and not playing my instrument for weeks at a time. I really needed that. And I still do that today, because I want to heal my relationship with my instrument. So that’s really hard to face. Because you’re watching your peers or your colleagues have a pretty good routine going and getting better, and I just had to redefine what getting better looks like for me. For me, that’s just mentally being more loving and open towards my instrument. So now if I feel like I’m going to have resentment or feel like I’m going to be angry or negative towards my instrument, I’ll hold off practicing.

Krissy: That’s beautiful, though, the way that you talk about the relationship with your instrument, I think that’s really wise of you to be like, space is okay. It’s going to have to be okay because how I feel about this matters. And it impacts everything because, being musicians, the sounds that we make and what we’re feeling are so deeply in relationship and intertwined that you can’t really separate that. It’s unsustainable to continue practice with feelings like that. And so I think that’s really wise that you saw that and have acted on it, even when it feels counterintuitive.

Tabla is a really primary source of how I can express [myself]. Cultivating a voice on that instrument has been a really important part of who I am as an artist, but I think there are other ways to express around and underneath that.

Kate: You segued, Krissy, to another question I was going to ask you about translating internal feelings into music or into an external form. Building on this awareness of the body that you’re both talking about bringing into your practice sessions, I’m wondering how that process works for you.

Krissy: Tabla is a really primary source of how I can express [myself]. Cultivating a voice on that instrument has been a really important part of who I am as an artist, but I think there are other ways to express around and underneath that. The experience that I’ve had with M³ has really gotten me to this deeper, more base layer of how to be expressive as an artist, regardless of the media or instrument. The writing portion, too — being able to write a work that I knew was going to be published with other artists’ works was really powerful, because I think writing was my first artistic love before I even started playing music.

I remember being a little kid, laying and looking into the eyes of my cats, and I remember thinking that it looked like an aerial view of the desert. I wrote this whole poem about my cat. I found it last year. Returning to that stuff is so precious and special. These are the first creative buds that I had, before I knew so much about how my journey was going to pan out as an artist. Being given the opportunity to return to that is really special. Taking those internal observations, or those things that I’m connecting with in the world, has been a big part of how I started that journey and how I tend to express.

Naomi: This was something that took me a long time to work around or just be more aware of, in a sense. For me that also translated to [an interest in] poetry — there was a part of my practice or composing where I was really getting into the styles and the different rhythms of the words and really drawing a lot of inspiration from poets. Also, with translation, I’m starting to think a little bit more about what that looks like as a musician who’s also neurodivergent and what translation looks like in a communication setting. Because I don’t think it’s really talked about very often. Or maybe it’s that musicians are just supposed to be one way. Or sometimes you don’t really get to know musicians as personally as you’d like. So there’s just one layer of this person you meet. I would like for things to be more transparent about the different workings or mindsets of all the musicians, and just being more aware when we’re meeting new people, and making that into a practice when we’re stepping into a new community.

[ID: A black cat with green eyes stretches out on a bed and looks up at the camera.]

Kate: That gets into another question that I was about to ask about how to navigate these internal, not fully internal, because they show up in external ways, obviously, but these identities such as queerness, and neurodivergence. How do they impact your work?

Naomi: I would say these aspects have impacted my life in general — not just in music, but my life — greatly. I’m trying to make it more of a practice to blend my regular life [and music practice]. Right now, it still feels kind of separate. But I want it to come together. And that also [means] addressing that my mind functions in a different way. And then also being queer too, and talking about how that affects conversations in certain communities. For me in terms of my own music and how it’s impacted the way I compose and the way I perform, it really comes out when I’m talking about my music, and what that looks like for me as a bandleader. Because ultimately, my goal is to just create more safe spaces and also realize that some people aren’t aware of what it’s like to create a safe space.

Those two things have created more awareness for myself and how I approach writing, how I approach meeting other people, and even just how I approach improvising or solo playing. For a long time I always felt that I had to play a certain way because I looked a certain way, or play louder. Because for some reason, coming into college as a woman, the expectation was just that women don’t play as assertively. That’s how those two parts of myself have impacted me as a musician.

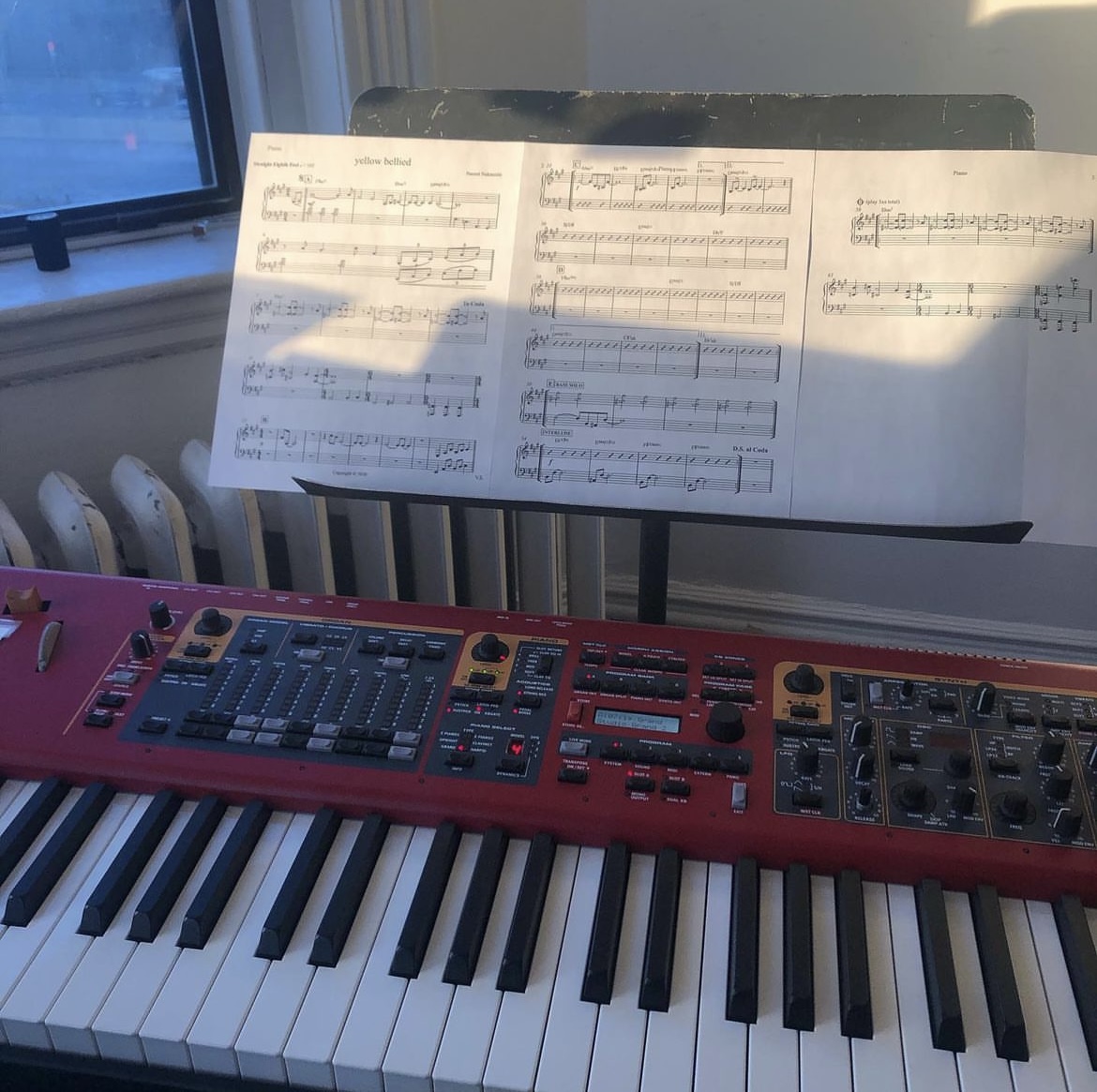

[ID: An electronic keyboard set up in front of a window and radiator. Light from the window plays on the sheet music displayed on the music stand.]

Krissy: I really like what you said about blending your identity with your artistry and musicianship, and I definitely relate to that. Because in one sense, you can acknowledge it’s insidious the way that those expectations creep in. And then you realize, I’m holding myself to a standard that I don’t need to be, or doesn’t even resonate with me. I feel that very much being a white chick playing tabla. It’s a very machismo world and there’s a lot of emphasis placed on really rigorous practice. I’m always riding the line of really feeling like I owe so much to the tradition, and I can absolutely see the beauty and value in this deep tradition. But then on the other side, there are things that need to be left behind, and that’s not always my call to make, but I think sometimes within my own personal choices, it is and it can be.

Even something as basic as the sound that you’re producing, because I’m not a very loud player, I’m a pretty gentle player. If you could put me in a listening room, and just let me play quiet things all the time, I’d love that. I love it. All of the detail and the sensitivity is just where I love to be. It’s a big juxtaposition against what a lot of people expect or want from tablas. It’s this shredding instrument, but it’s not really about that all the time, it’s about what we have to say using whatever instrument we are using as a medium for expression. I really loved what you said about blending your artistry with your identity. That has also been a really long term process for me as well, of how am I showing up more as myself, instead of trying to fit inside of an expectation that wasn’t even mine to begin with.

How am I showing up more as myself, instead of trying to fit inside of an expectation that wasn’t even mine to begin with?

Kate: So in our last little bit of time here, I’m curious about what making a safe space for a group practice might look like — if you’d be willing to share.

Naomi: One of the things that I find most important is mainly when it comes to the improvisation setting. As a pianist, sometimes I really do take on this accompaniment role, I love giving a chance to explore sounds with another musician and then having to take on a supportive role. But I find that for me, sometimes that just looks like making sure that everybody does have a chance to solo or improvise or try something out, and taking a step back and actively listening all the time.

Another thing that’s really important is the pre-playing conversations. I think it’s nice when everybody sits in a little circle, so it just feels a bit more casual. I want it to feel like this is something that’s going to be fun, in a way. I know if it’s a rehearsal, so there has to be some level of seriousness maintained, but I think it’s really important for the musicians I’m playing with to feel cared for, and feel respected. Respect is a huge, huge thing for me.

I know what it feels like to be openly disrespected, publicly, from both peers and teachers, and it’s really embarrassing. I would never call anybody out for not knowing a tune or being hesitant about improvising, or being new to playing in ensembles. I think it’s really important that everybody feels like everybody knows that they should be there, that there’s a reason why they’re there. And that they feel like they belong. Also, pronouns pretty much should go without saying, but I’ve noticed that in music communities, not many people ask about pronouns. That’s simply an important part of making sure that their identity is being heard and validated.

Krissy: I loved everything that you were talking about, because it really speaks to clearing the slate of other people’s expectations for you, and instead creating a space for people to show up deeply as themselves. Making things together and making music can be so intimate. All of those conversations about what we’re feeling and thinking and what feels best for everybody in terms of how we’re showing up to a space together, what the boundaries are, what the rules are, what our own personal expectations are for a setting, are really important and create a new, more stable, more enjoyable foundation for people to create from. Because you can’t access curiosity in a space where you don’t feel respected or a space where you don’t feel comfortable or feel overlooked or not seen or not heard. When you can create those spaces, that just creates room for more intentional and beautiful art to be happening from a deeper and truer space for everybody.

Header Photo Credits:

Photo of Krissy Bergmark by AJ Williams; photo of Naomi Geena Nakanishi by Lauren Desberg.

[ID: Krissy, a white woman with long wavy brown hair, stands on a bridge smiling and holding a tabla. Her blue tank top shows off a floral tattoo on one arm.]

Krissy Bergmark

She // Her // Hers

Chicago, IL

Krissy Bergmark is a tabla player, percussionist, improviser, and educator who centers her creative work on bringing tabla to new genres and cross-genres through composition and performance with a grounded understanding of the traditions of the instrument. Bergmark has received commissions and grants through the Cedar Commissions, the Jerome Foundation, the Metropolitan Regional Arts Council, and the Minnesota State Arts Board. She composes and performs with her progressive folk trio Sprig of That, and a variety of other artists in Minneapolis, Saint Paul, Chicago, and New York. Her current solo project, with the working title Water Frame, explores the juncture of family history, body memories, and epigenetic inheritance through sound, visuals, and physical sensation. Her debut album, an in-studio improvised work entitled Everything’s Glacial Shine, is set to be released in early 2024. Bergmark is an adjunct professor at Oakton College. She studies tabla with Pandit Yogesh Samsi in the Punjab Gharana.

krissybergmark.com

Instagram: @krissybergmark

[ID: A Korean-Japanese-American pianist with short hair and Lilith shaped earrings fiercely standing with their mini keyboard.]

Naomi Geena Nakanishi

They // Them // Their and She // Her // Hers

Brooklyn, NY

Naomi Geena Nakanishi is a dynamic pianist, improviser, and composer who invites their listeners with distinguishable melodies, sonorous harmonies, and unconventional phrasing. Nakanishi’s music aims to reconstruct, experiment, and interact with sounds influenced by their comprehensive background in Black American Music, indie-folk, R&B, and classical piano. They seek to inspire and continue learning from multiracial, queer coalitions while curating more culturally rich and interactive experiences to all who listen to their music, and they recently conducted a series of workshops on racial and gender equity/identity through the Women of Jazz and Creative Music organization and the Esperanza Academy in Boston. Recent studio work includes their debut EP, Hear Me Speak (2022). In addition to performance, Nakanishi is also passionate about music education and has served on faculty as a private piano instructor.

naominakanishimusic.com

Instagram: @nakanishimusic