“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” —Octavia Butler

25-30 minute conversation, or the time it takes for a midday stretch.

![]()

A CONVERSATION WITH JESSICA JONES AND ZEYNEP TORAMAN

To create with intention is to work slowly and deliberately, taking time to foster trust between collaborators and maintain integrity in creative decision-making. For composers and musicians Jessica Jones and Zeynep Toraman, this focus on a process of slow unfolding is crucial, particularly because these periods of rigorous collaboration are equally interspersed with moments of composing in deep solitude, sometimes even without an audience. In the following conversation, Jones and Toraman reflect on their experiences prioritizing trust-building during their residencies and finding a balance between meticulous planning and embracing the unexpected.

Jessica Jones: Hi, I’m Jessica [Jones], and I’m a composer, pianist, and saxophonist. I lead my own groups, and I’ve been working with improvisation for many years. I was a member of M³, and this was my first time collaborating online with people and working so deeply. I loved it, and want to talk more about it.

Zeynep Toraman: I’m Zeynep [Toraman]. I’m a composer primarily. I’m from Istanbul but right now am based in Berlin, and I’m also part of M³. I’m happy to explore different types of music-making these days.

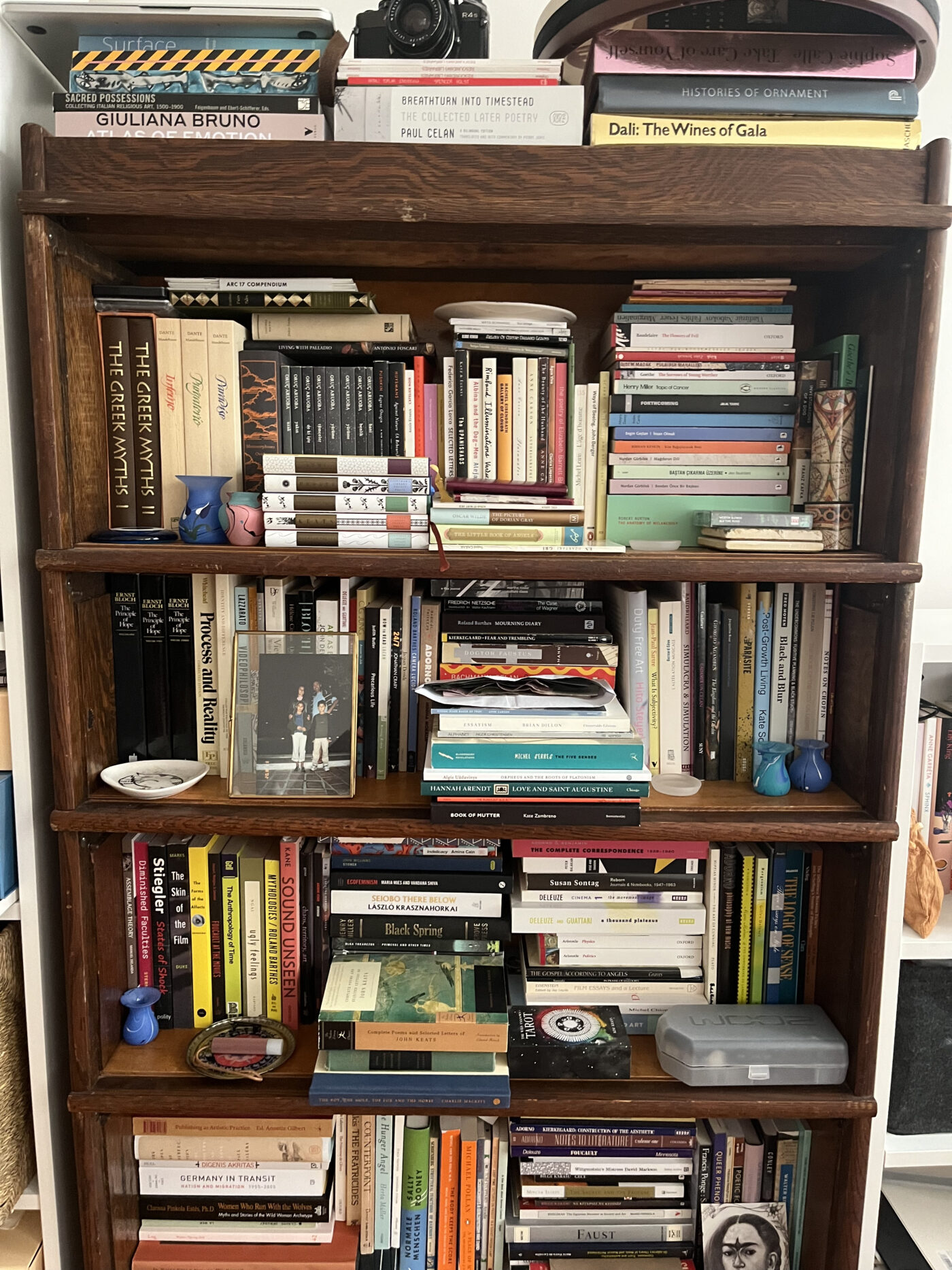

[ID: A dark wooden bookcase filled with books stacked in various arrangements, small ceramic vessels, photographs, and other objects.]

I’m always so amazed how I can gather these little threads from all of these voices that are external to me and be able to find a reflection of myself in these works that are speaking to me so deeply in that moment.

Allie Linn: I was really struck by how much overlap there was between your respective contributions to the Anthology [of Writings] as two explorations of the formation of the self, or what you refer to, Zeynep, as the “endless makings and remakings of a self.” Jessica, in your text, you have gathered moments from your diaries from ages fifteen to sixty-one, and Zeynep, in yours, you reach externally to the texts that have influenced and shaped you throughout the years. Can you each share a bit more about the process of crafting these autobiographical and existential collections?

Zeynep: I think this is, in general, something I’m really interested in because alongside music, I studied quite a bit of literature during my doctoral studies. I am really fascinated by all of these texts — also music, text as a really general kind of idea — that everything that I’m interacting with at the time creates this pool of references that I’m drawing on so intensely. I picked those books for the Anthology because they were my current reading list — the books on my desk, basically. I’m always so amazed how I can gather these little threads from all of these voices that are external to me and be able to find a reflection of myself in these works that are speaking to me so deeply in that moment. I used the Anthology entry as an exercise to foreground threads that were present in my in-the-moment psyche. It’s really fascinating to hear that we got paired for this randomly, but it was touching to see Jessica’s entry being the diary, archival method. It’s a really nice pairing.

Jessica: The thing about keeping the journal — I would call it a journal because a diary sounded too girly when I first started doing it — a friend of mine gave me a journal to work with when I was thirteen, and she went on to become a classical pianist and a writer. We both kept these over time, and the thing that I have found interesting is going back and looking at the strings of who I always have been and the parts that have changed or crystallized and become more mature. While I’m writing, there’s no self-editing or thinking about who’s reading it; it’s just a way to process my own thoughts and to see what they look like and let them come out of me, which feels a lot like improvising. I feel like the writing process for me is very similar to improvising and is a model for feeling natural when I’m improvising music.

While I’m writing, there’s no self-editing or thinking about who’s reading it; it’s just a way to process my own thoughts and to see what they look like and let them come out of me, which feels a lot like improvising.

Allie: It’s clear that the boundary between improvising and composing is really blurry and that you each are working in both of those worlds — Jessica working from a tradition of jazz, which has such a background in improvisation but is still so dependent on composition, and Zeynep focusing more on the composition side of things — so I wonder if you could each talk about that combination of improvisation and composition.

Jessica: Coming from jazz, improvisation is a real basic thing. It’s basic in that the goal is self-discovery and to really find out how you want to be in the world or what your true voice is. I love the journey of it and that there’s no real goal. There’s no real set place where you arrive. The compositions tend to be inspiration for improvising. I think sometimes when people listen to jazz they just think of it as, “There’s the composition, there’s the improvisation, there’s the composition again.” Head, solo, head.

That is the shape of a lot of music, but, luckily, you can find people to work with who are understanding of what they should bring to the music, including altering the composition to how they want to express it. There’s always some personal improvisation involved, even in composition, which is not an aesthetic that’s necessarily true in other kinds of music or in the way that people interpret other kinds of music. In classical music, people tend to think that there is a way to play something, even though we’ve never heard the original people play it, so we don’t really know. I think in jazz there’s more understanding of really wanting to hear different people’s takes on it, even in the composition.

And I think that recently the lines are blurring between composition and improvisation in jazz. If you listen to something, you can’t always tell which is which, which is fine and good and healthy, because all we’re doing is expressing ourselves. Things are definitely a mix, and it has more to do with who you’re playing with, whether it’s a composition or improvisation.

Zeynep: This topic is quite difficult for me because I mostly work in the realm of notated music or recorded music. I make electroacoustic music that’s set in time, but I would consider myself a really intuitive composer. That’s how I like working, but the irony is that to create these kinds of forms that seem to unfold in time in this very immersive or very psychological way, I have to plan the temporality intensely. To create something that sounds really organic and naturally flowing, I spend quite a bit of time questioning how I hear things personally, as opposed to just writing in chronometric time. I’m thinking about how it is going to be heard when it’s actually just vibrations in the ear that we end up hearing. A big part of my practice is listening and going back and forth between the music and what is in my head. A strange part of this work is that I don’t get to talk about it so often.

Jessica: That’s interesting, though, because I think it’s similar for an improvising jazz musician. You would be practicing all of these different ways of doing things so that you have a tool to unfold something the way you want to unfold it. It sounds like when you say you’re an intuitive composer that you’re also saying you have an idea, and you’re improvising how to use it, and then you’re perfecting it. You’re going back and figuring out if that’s the true representation of what you’re trying to do. So the impulse is the same, and a lot of the process is the same.

Zeynep: Absolutely.

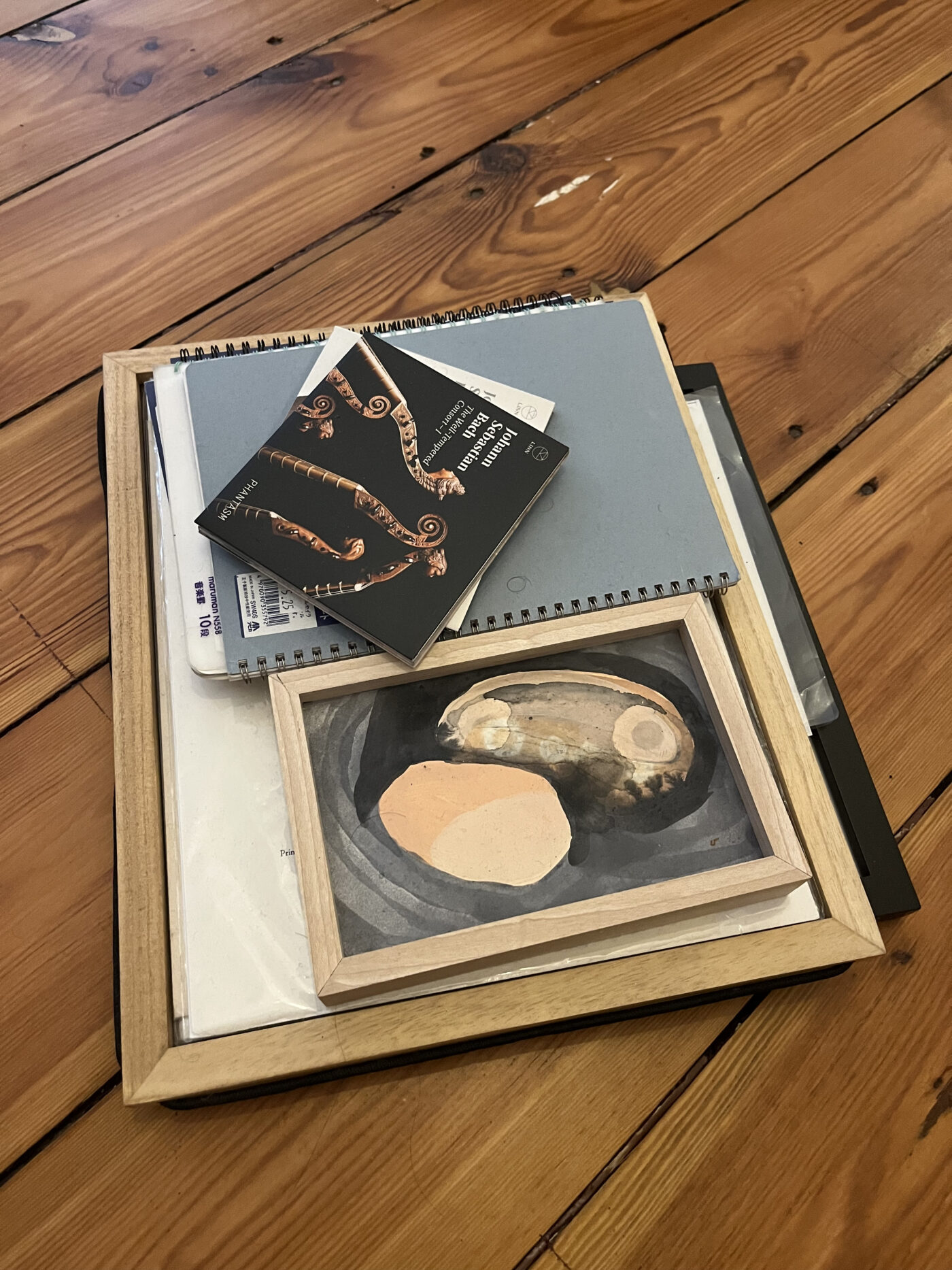

[ID: A collection of objects stacked on the floor. Two CDs, an abstract watercolor painting with peach shapes in a sea of gray, and several spiral notebooks laid on top of picture frames.]

Allie: I’d love to hear a little bit more about that process, both for the music and the writing. Returning to your journals, Jessica, or returning to these texts and literature, Zeynep, that you reference in the syllabus that you’ve crafted: is that an ongoing process for each of you, or was this really a moment to sit down and look back on a collection and think about editing and arranging?

Zeynep: For me, personally, this is absolutely how I work all of the time. I have a lot of ambiguity around my own identity. I’m Turkish but I have spent my entire adult life in the US and interacted mostly with the Western canon in my academic life. These different ways of combining texts, which are unusual, or not what we’re encountering in the classroom, have helped me with self-determination around my identity. I have some agency around how I interact and activate these texts to get different lines of dialogue happening between them, often pairing these “canonical” texts with much more “obscure” voices from a non-Western canon or very contemporary authors. I’m able to continue both reading a lot of this material that I love so dearly but also somehow redeeming and finding some reconciliation in it myself, and that’s really at the core of my compositional practice in the end.

Jessica: Wow. It’s sort of like you’re translating your perspective by putting two other objects together to say what you’re trying to say. That’s very cool.

I am not used to editing. I’m used to working really hard and then first thought best thought, just letting it go and learning from what you just did. When you asked about the writing in particular, when I write it, it just comes out. Going back and looking over it, I had a really severe want to not touch it or in any way change it. I cut it way down from what it was; there’s something about respecting the part of yourself that first did it that you have to be careful of. I definitely err in that direction, rather than making it clear, because I’ve also found that a lot of the writings I’m attracted to are the ones that a lot of people don’t feel make sense.

There are people that can hear what you hear the way that you hear it, but you won’t know, you won’t be able to connect to them if you edit it, because you’ll never find them. It’s like putting out a beacon of who you are so that you can find your people. If you alter it to what you think might work, you’re going to get different people. In that sense, I try not to edit, and that’s probably a fault, but I err in that direction.

Zeynep: Yeah, that’s quite beautiful to hear. This idea that you believe that the music creates its own audience or you find your tribe —

Jessica: Right.

Zeynep: — while just letting things exist in their own ways. I find that super powerful.

Jessica: That’s what I feel about the things I’m attracted to. What made them do something so different from everybody around them? They weren’t trying to be different, they were just not trying to make themselves be the same. I find that inspiring.

There are people that can hear what you hear the way that you hear it, but you won’t know, you won’t be able to connect to them if you edit it, because you’ll never find them. It’s like putting out a beacon of who you are so that you can find your people.

[ID: A colorful sunset with salmon pink and yellow clouds with the silhouette of a mountain in the distance and trees in the foreground.]

Allie: Zeynep, when I was listening to “The Sea They Think They Hear,” I was thinking about how many of your works have a very immersive atmosphere for the listener. That one in particular really captures this eeriness of strings and vocals that seem to transform into a landscape and its otherworldly creatures. I was curious to hear more about the process of moving from idea to notation and recording for you. Do your works begin with an image or an idea or something else?

Zeynep: Thank you, that’s really nice to hear. When I wrote that piece specifically, it used a lot of textual references around the sea. I thought to myself that it was one way to combine texts, this common theme of the sea metaphor. I wrote the text first, and then for the sound, image, or idea, it was a bit of both. The title comes from Ulysses, the “Sirens” chapter. In the bar, they’re listening to the seashell, and there’s a simulation of the sea sound. I thought to myself, “Why don’t I try to create that idea, not the actual sound of the sea, but this simulation, this booming effect of listening to a seashell sonically, temporarily?” I actually created the spectra that I work with and the kind of instrumental writing that creates that effect. I like this idea of immersive soundscapes that take you in. They unfold around you, and then they end somehow. The endings are usually problematic.

Allie: Jessica, I thought it was so interesting that I saw so many connections between you and Zeynep’s collaborative videos and soundscapes that you produced through your residencies at M³. There was a lot of water imagery and waterways in your work, as well, and I also wanted to hear your thoughts around this recurring image of water.

Jessica: That was a combination of images from me and Rosángela [Pérez Molero], who was my partner. We were looking at feet, and some of the feet were in water, and some were on stairs. Water and natural scenery took on a big part of what we were looking at. In that visual collaboration, we each brought our own images and some of them crossed over and some of them were unique. We definitely had a more abstract connection. We wound up making soundscapes and visualscapes that did cross over in the same realm. Rosángela is also very abstract and has no problem taking time with her sound. That was a big influence on what we were doing. That idea of unfolding and taking your time was something I’m less used to. It was a nice influence in there and is maybe part of the crossover of what you’re hearing, too.

Zeynep: That’s quite beautiful about the sea and the metaphor of water as this thing that you can’t tame. I like that thread sweeping over to this world of sound and how clear that metaphor is for everyone and how it manifests in both of our collaborative projects for M³.

Jessica: Rosángela is a child of a poet and a visual artist. Colorwise and texture-wise, she brought a lot of ideas. She also had already done videos of her own music that were very textural, and so she had a lot of very specific ways of imparting some of the visuals we were talking about and was able to communicate those very clearly to the video artists. That was really helpful in our collaboration. She had already synthesized her different ways of seeing and sounds really clearly, so when we had busier, denser things, we could talk about ideas of how that would be visually represented. Sometimes in the pieces that we improvised, she would say, “This sounds like this color to me, and I really want this color to be in it.” She was a very strong influence on the video and also really excellent for me to collaborate with because it made me see things in a different way and also helped with the language of how to bring the music to a visual point. How about you, Zeynep?

Zeynep: We quickly realized that Kavita [Shah] and I have a lot in common in terms of all these cities by the water that we feel associated with and that play a big role in our personal histories. We decided to follow this common thread of water to connect these geolocations and took an autoethnographic approach. We used all of the videos that we had taken in these cities by water. We were mostly living in these places or studying in these places, so they represent these more active, social, directed parts of ourselves.

I think with the water, we were able to tap into this more emotional and submerged side of how we felt at the time and what these places meant to us. I quite enjoyed the process, even though we were so far apart. It’s amazing how such a collaboration brings you so close to someone. I’m most moved by that in the M³ experience: how quickly that bond developed for us. The piece is really personal for both of us, and I’m sure it’s the same for you, Jessica, and Rosángela.

[ID: An angled view of several glassy skyscrapers of varying heights reflecting some sun against a gray sky.]

Recently I’ve been experimenting with writing music that’s pleasurable to play, thinking of the performers as my dear colleagues that I’m working with, and not shying away from creating something that’s beautiful, fun to listen to, and fun to play.

Allie: I’m also hearing that it’s such an exercise in trust, having this type of collaborative work. It’s making me think about your work straddling the edge of improvising, planned and not, Jessica, and how much trust is built with your collaborators over the years. I’d love to hear a little bit from both of you about the specific methods you have for collaborating to translate all of these various practices or ideas into one cohesive whole when working with other peers, organizations, or institutions. What is it like to work with somebody for the first time versus, Jessica, some of these bandmates that you’ve been working with for so long?

Jessica: First of all, shout out to M³, because one of the things I think was really palpable is there’s an unabashed understanding that it’s okay to develop relationships as a priority before you start to work with somebody. I think a lot of situations that I get [into] say that stuff doesn’t matter, let’s just do the work, and it makes me very uncomfortable. It’s hard to be vulnerable in those situations, and I think what made us work so well together had a lot to do with how they created a community quickly and built our trust with each other.

I am more comfortable improvising with people if I have had conversations with them, and know a little bit about them, and feel safe, in whatever way that is. Some people are braver than me, but I need to feel safe. I think that’s not unusual, but it’s not usually the first place people go. Obviously, the people I’ve played with for years, I have that feeling with them because we’ve built over time some kind of trust and understanding about taking risks, allowing risks, honoring somebody else’s input, and being able to not accept somebody’s input.

I think it’s interesting the way you ask that question because you’re talking about going into these different situations and having a process that works for what you’re doing. I just finished a residency where I had to take a small chamber orchestra of people that I hadn’t worked with and have them improvise together. There are a lot of things about accepting people as human beings and who they are and making them understand that everybody is okay and then you can start, as opposed to, “I am judging you on how well you interpret my music,” or “You should already know how to do this.”

A lot of interpersonal strengths that I’ve had to build as a teacher, and as a mother, and as a person on the planet who has to interact with a lot of people are very useful in these situations because I’m sensitive to recognizing some personal things and am able to work with the individuals involved and go on to the music from there.

Zeynep: I am so moved by what you’re saying, Jessica, about it being okay to develop personal relationships while we’re working as musicians. In contemporary classical music, too, you write the piece, you go, people rehearse. I was really mentally struggling with this: I have to go give someone a score, and they’re supposed to execute it perfectly, and that’s the job.

Jessica: Right.

It feeds you more to be in relationship with people than to be a genius.

Zeynep: Recently I’ve been experimenting with writing music that’s pleasurable to play, thinking of the performers as my dear colleagues that I’m working with and not shying away from creating something that’s beautiful, fun to listen to, and fun to play. Even if it’s hard, it’s still not torturous. When I say this, I think people find it strange, especially in the contemporary classical music world, but it has influenced how I write. There’s so much stigma around wanting to write something that’s beautiful and pleasurable in the main niche that I work in, but it has helped me psychologically to break away from that and just build these different types of working dynamics. It’s so nice to hear you also speak out.

Jessica: It’s interesting that you can use the music to do that.

Zeynep: I just did a piece in France when I was there last week. I was so happy because the piece is what it is, but the trio was just having fun. It felt meaningful. That’s so special to me, more so than having a really difficult piece shredded by some really fancy ensemble in a fancy festival.

Jessica: It’s really about the connections between people in the end. Even if it’s AI, it’s still something about connecting.

Zeynep: I think in jazz that’s so much more obvious than how I work. For M³, that was what was different for me. Kavita and I were actually doing something together, which is so humbling and different and amazing. Maybe in improvised music there’s this sense that everybody is immediately making something happen in that moment, together, and that’s much more palpable sometimes than the decorum of classical music that I work in most of the time. I feel like rebelling in this really quiet and nonaggressive way is really fun for me in the moment.

Jessica: Classical music and the music models that we’re used to tend to have the genius or the person in the front, the conductor, “the one,” and then everybody is just realizing the “chosen one’s” stuff. It’s politically very different to be on the ground and have everybody involved, and it’s just about them and their stuff together and not idealizing and idolizing one grand person for being talented. It feeds you more to be in relationship with people than to be a genius.

[ID: A patch of vibrant red flowers with dark centers blooms out of a grate at the bottom of a stone wall and tumbles over the cobblestones.]

We’re professionals, so I could make something happen fairly quickly if I had to, but I know personally — and I feel this accountability to myself — to take the time and resist and actually protect the work.

Allie: I’d love to end with a note you reminded me of, Zeynep, thinking about the timing of some of these projects. You said a phrase earlier: how to “plan the temporality.” How do you both think about pace in your practice in relation to composing, to playing, to touring, and to all of the other facets of your day-to-day life?

Jessica: You’re asking that question in a macro and a micro way, so it’s pretty interesting. I often get caught up in my daily two-hours-of-this, one-hour-of-that. I have realized over time that there’s a sequential balance, as opposed to a daily balance, that sometimes happens: playing a lot for a month, and then composing, and nobody hears it and there’s no feedback, and there’s nothing for a couple of months. Then there’s a workshop with a lot of people for two weeks and you’re on all day. Then a month where you just ride bikes and get yourself together. Over time, there’s a balance that I’ve surrendered to, as opposed to trying to make balance all the time, every day. I do really value having many parts of myself addressed in a consistent way, meaning staying healthy, staying outside, being with people, being away from people. I feel like there’s a rhythm to that, in the long run and also on a day-to-day basis. It’s taken a while to get there, to not be stressed about that concept.

Zeynep: What you’re saying definitely resonates with me so much because I think being a musician is spending large chunks of time alone and then just being really immersed in social situations. Prior to France, I hadn’t really left my house for three weeks, and then I was at a festival surrounded by people for ten days. That’s a hard dynamic to balance for me at times. I’m a very slow person. I like reading slowly and writing music slowly and just taking my time. So [I’m] trying to find optimal ground between responding to the pressure of producing more work and sharing that with the world at an acceptable speed that keeps [me] relevant somehow, and also allowing myself to enjoy just reading a book at a very slow pace or just working on some piece for an extended amount of time. I’m in my head a lot with the composition, too. I’m sure you would agree, Jessica, that the amount of time that one has to spend just thinking about the work is as important as the times you have the pen in your hand on your writing or you’re just doing it, so I think since it’s nonstop it’s hard.

Jessica: Have you found yourself being more forgiving about that? “Hey, this is who I am. I take a slow pace, and it gives me a different view than I would have if I were pushed.” Have you been more understanding of that as you get older?

Zeynep: Yeah, I think so, but it’s hard. Leaving the doctorate program that I was enrolled in and having graduated and being in the real world, the freelance pressure is definitely real, but I think to keep a level of integrity in the work, I can’t produce faster than a certain limit. I was just talking to another composer about this, and he was saying, “one knows when they’re being truthful to the work.” It’s so easy to produce something because we all have our tool bags. We’re professionals, so I could make something happen fairly quickly if I had to, but I know personally — and I feel this accountability to myself — to take the time and resist and actually protect the work.

Jessica: Yeah, because there was fast food and then there was slow food, and slow food got really popular because people were stubborn: “I understand that’s more convenient, but this tastes better.” It’s the same thing with taking your time. You can be the leader on that, instead of feeling like you’re catching up to somebody else’s expectation: “This is what I do, you guys are not on board yet. Anybody who wants to slow down, get behind me.” The world needs those things.

Header Photo Credits:

Photo of Jessica Jones by Frank Stewart; photo of Zeynep Toraman by Sena Ayden.

[ID: Jessica, a white woman wearing a gray fedora hat, black shirt, reflective sunglasses, and beaded bracelets and necklaces, embraces her saxophone in her lap.]

Jessica Jones

She // Her // Hers

Hudson Valley, NY

Jessica Jones leads a pianoless group, the Jessica Jones Quartet, which features her original music and has produced several critically acclaimed recordings. The group received a Jazz Road touring grant in 2019. Jones is also active as a sideman and has worked with Joseph Jarman, Cecil Taylor, and Don Cherry, as well as a variety of Haitian, Caribbean, and African bands. She is a recipient of the inaugural Jerome Artist Fellowship Award in 2019 as well as grants from the NEA and the Jubilation Foundation. She is a jazz educator and consultant, working with children on improvisation, composition, and oral traditions for Jazz at Lincoln Center, Stanford Jazz Workshop, Bard College, the Vision Festival, and Brooklyn Friends School. Currently, Jones is an Artistic Director for REVA, Inc., a non-profit created to use creative arts to inspire, educate, and heal people and communities.

jessicajonesmusic.com

Instagram: @reva_inc_org

[ID: Zeynep, a fair-skinned woman with long brown hair, sits on a small white bench in front of a blue-tiled wall and an acrylic pane, revealing a staircase behind it. She wears a black long-sleeve shirt and pants and looks directly into the camera, smiling softly.]

Zeynep Toraman

She // Her // Hers

Berlin, Germany

Zeynep Toraman is a composer and scholar from Istanbul, living and working in Berlin. Toraman’s practice-based research explores the ways in which texts — in the broadest sense of this word — can interact with one another within the larger framework of musical compositions, by way of thinking of her own library as an archive, and enfolding autobiography, poetry, fiction, and history within her works. Her music has been performed at festivals including Darmstadt Ferienkurse, Summer Academy Schloss Solitude, IRCAM ManiFeste, and Wet Ink Large Ensemble Readings, and her research has been supported by the German Academic Exchange Service. Toraman has taught at the Institute for Electronic Music and Acoustics at the University of Music and Performing Arts Graz, and she completed her PhD in Music Composition at Harvard University, where she studied with Chaya Czernowin, Hans Tutschku, and John Hamilton.

zeyneptoraman.com

Instagram: @tora_zeynep