“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” –Octavia Butler

“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” –Octavia Butler

30 minutes or the time it takes to repot a house plant

What does creativity look like when pain is a daily collaborator? In this conversation, artists Finnegan Shannon and Emily Sara talk about the nonlinear work of honoring their limits and devising ways of working that defy ableist norms. Most importantly, they remind us of the power of small treats to sustain oneself.

A CONVERSATION WITH

EMILY SARA AND FINNEGAN SHANNON

Ezra Benus: To begin, how do you like to keep and spend time?

Emily Sara: Well, Finnegan, I feel like since you have made clocks as part of your practice, this is an especially good question for you. I can talk after you, if you’d like to start.

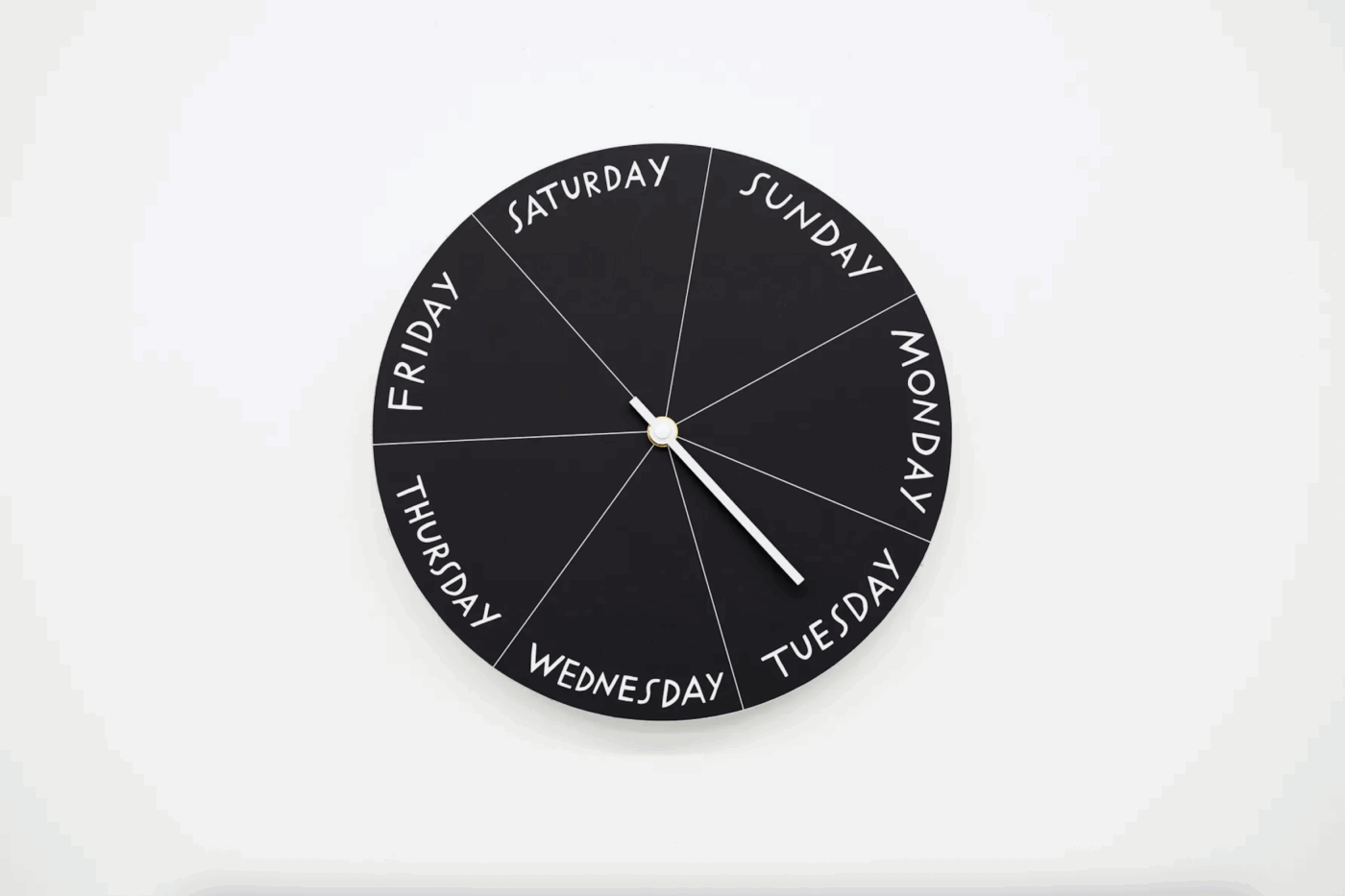

Finnegan Shannon: Yeah. I had this experience seeing a clock in a friend’s parents’ house and falling in love with it; it’s called a Day Clock. Instead of marking the hour and the minute, it only marks the day of the week, and the clock hand moves really slowly. It makes a full rotation in seven days. I’m always interested in things that are connected to disability cultures, and I had this moment of resonance with the clock.

It is also marketed as an assistive device for people who need help being oriented to the day of the week. And as someone who physically moves slow, I just liked that it also moves really slowly, and actually you can’t even really tell if it’s working or not because it moves so slowly. I first had one that I lived with in my apartment, so it’s definitely a way that I keep time and then later also turned it into an artwork.

Emily: Sorry to put you on the spot there Finnegan, but it’s one of my favorites. I thought this was a great question, Ezra, because I don’t have a very good relationship with time, personally. I think so much of our time in society, and this goes back to what you just were talking about, Finnegan, is actually built on “normalcy” — traditions, socially constructed rules and basically, capitalism.

I think of my body as outside of the realms of “normal.” So much of my time is based around how I’m feeling, because my bodily capacities fluctuate significantly and even severely at times. And because of this, I often don’t feel in tune with other humans, even people I love dearly.

[ID: A clock. Instead of showing the hour and minute, it indicates the day of the week. Its hand moves very slowly making a full rotation in 7 days. Here it points to Tuesday. The days are written in Finnegan’s handwriting, smooth but slightly wobbly capital letters.]

Ezra: How do you understand the relationship between time and pain?

Emily: I feel like pain warps time for me. Do you feel like that, Finnegan?

Finnegan: Well, I was thinking going into this conversation, we haven’t talked directly about our experiences of pain, but from what I know about ways that you’ve publicly talked about pain, I think we may have different relationships to it.

I actually feel like the flare is not such a big concept in my life and my pain. I experience a more constant low-level drain. So for me, with time and pain, it is sometimes almost a feeling of being in molasses or something like that. I guess that is a type of warping, to go back to what you were saying. But I know friends and colleagues and strangers who have a much more unpredictable relationship with pain and with the way that it shifts time.

Emily: I guess since I considered myself, and was considered by others, as non-disabled at the beginning part of my life — it wasn’t until later in life that I realized I’ve actually been disabled this whole time. So I think I also have grasped the perspective of what a non-disabled perspective around pain is, if that makes sense?

I’m just thinking back to the time when I was in my early thirties; I went to a doctor and they were like, “So how often do you have pain?” And I was like, “Oh, the normal amount. It’s every day with varying degrees of severity.” And they were like, “The normal amount is zero.” And I was like, “What?”

Finnegan: My mind can’t compute that.

Emily: Exactly. And same. I somehow went most of my life thinking that was normal. Part of it was definitely a result of medical gaslighting, denying the severity of my pain when I tried expressing it as a kid and young adult. But like you were saying, there’s some people — and I think especially from a non-disabled perspective — who see pain as brief, intermittent moments, like a broken arm or the flu or something.

Being neurodivergent, I also think that there’s a pain that comes with not being able to always communicate with certain people. Or rather, that some individuals judge me or do not like my way of communicating and shut it down — whether they realize they’re doing that or not. But I think neurodivergent individuals also carry a type of communication pain that can be another layer on top of having a physically embodied pain, of sorts.

Finnegan: I relate. Pain is just part of life. It’s not surprising. Earlier, you were talking about the idea of a broken arm. It’s not something that appears and then goes away. It’s air or water or something like that. It’s all around us all the time.

Emily: Yeah, exactly. For me personally, I have an overall fatigue and difficulty with walking and so forth. But with intense peaks or flares. It’s kind of like you’re sitting down and you’re having a nice afternoon, you’re getting your work done, and then all of a sudden a bull comes running through that was poked with a hot prod or something. Drastic symptoms can come out of nowhere for me, or from specific triggers like heat or extreme stress.

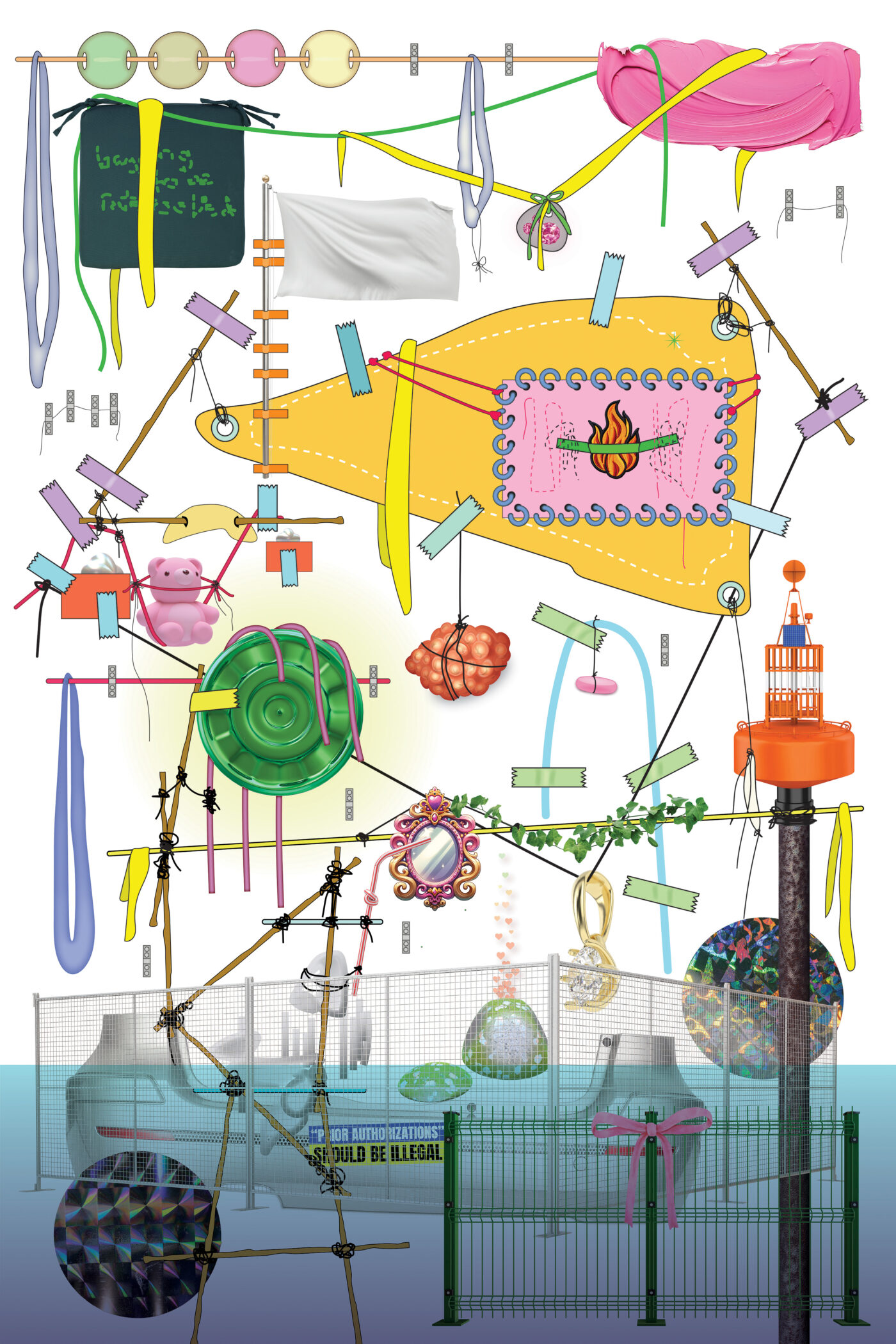

[ID: A large digital illustration composed of sticks, strings, and various assembled parts. The bottom edge of the image appears submerged underwater. Gravity feels present — objects show tension in how they are balanced, pulled, or suspended. Visible elements include barricades, a car bumper with a sticker that reads “prior authorizations should be illegal,” draped abstract fabric, a seat cushion, a diamond charm, holographic stickers, and a white flag waving in the wind. The overall composition feels haphazard and shifting, as if everything is barely holding on.]

Ezra: How do you understand the relationship between creating and pain? And then I’ll just add the next question: what draws you to making art about and in pain?

Finnegan: I’m really interested in artists who use their everyday life as the tools of their work. And because pain is part of my everyday life, it is something that can merge into the work or almost become a material in the same way that sometimes disabled artists talk about access as a material in the work. Pain can be a material in the work.

I also feel like I’m always trying to figure out ways of being an artist that honor my limitations… There’s a traditional model of an artist that has to do with extreme exertion and exhaustion; I’m trying to reject that model and think about the ways that I can actually make this work as easy for myself as possible. I’m constantly failing at that in different ways and then trying something new, and it feels like a never-ending process, but it’s something that I’m interested in. For me, it becomes a conceptual part of the work.

Emily: I fully agree with everything you just said. Especially pain as material and the trying to let go of traditional models of artmaking. I’ve been losing my ability to make certain types of work. With my sculptural work, for instance, I’ve been considering how I can use machines to make it for me. Or thinking about how, for example, I produce something once I’ve become allergic to a type of material I used to always use. Which has happened.

I think honoring those limitations and then being open to the malleability of the materiality that we use is so important. And what comes from that flexibility and retrofitting is one of the reasons why disabled art, in my opinion, can be so incredible.

For instance, I actually have a really hard time documenting pieces after I’ve completed them. Getting a white wall and physically hanging it up is just really difficult for me. And it’s honestly a huge hurdle for many of us. So in this instance, a disabled artist may totally reject that circumstance of hanging up a piece on a white wall because they just simply can’t do it. In turn, a disabled artist will have to get really creative with the circumstances they’re faced with — they redirect towards a solution that non-disabled bodies wouldn’t have to consider, in many ways. And in the end, that can create a totally different work than we as a public have ever seen before. In many ways that’s why disabled art is so unique, in my opinion.

Finnegan: I love what you said about sculpture because I do feel like there’s something specifically about sculpture that feels really hard. I definitely felt like sculpture would never be for me because of lifting things, carrying things, and the way that sculpture was presented to me had a very macho vibe to it.

I’ve found my way into a back door of sculpture because I do care so much about space and objects and material. And so figuring out a way to engage with that in a way that also works for me has been such a joy. It’s also something that I’ve learned from so many other disabled artists, about different strategies or ways of thinking about those things.

I think of my body as outside of the realms of “normal.” So much of my time is based around how I’m feeling, because my bodily capacities fluctuate significantly and even severely at times.

Emily: Yes, exactly. Strategizing alternatives. With sculpture, I’m now thinking about how I can be fabricating something that is quite large without having to leave my bed. More recently, with the Disability Futures Fellowship, part of what I did was invest in a 3D printer, which has been a huge game-changer for me.

I’ve taught myself some open source programs for 3D modeling. I have my computer, I pull it into bed, and I sculpt, for many hours, and then I go to sleep and — probably real 3D printers are going to be horrified when I say this — I have it print through the night. [laughs] Sometimes I wake up and there’s 85 million strings all over the place. I should note I now have a system for recycling those mistakes as well.

This printer is a ten-by-ten-inch box I can be working with, so I’ve been focused on fabrication that connects together. With what I’ve taught myself and further research I’ve put together, I’ve also opened up community dialogue around 3D printing as well. Through Cripple, the publishing initiative that I founded for disabled artists and designers, I’m currently hosting a series called “Fine We’ll Just 3D Print Our Own Wheelchairs (And Other Mobility Devices).” It’s really just about showing the work that has been made and highlighting the incredible research and designs that people are working on right now.

Finnegan: I feel like that’s another big one: working modularly. “Okay, I make this little piece and I make this little piece, and slowly those can build into something else or be different nodes of something larger.”

Emily: Totally. With the furniture that you make, it seems like so much of the shape is carried forward in the next iteration.

Finnegan: For those pieces, I can’t fabricate a bench. I can’t build a bench. I need other people to make that work, and I want whoever is part of the making to be able to influence the process. And so they take different forms based on where it’s being made and who’s making it. I try to come to the table with what’s important to me and then I also need the expertise of the fabricators and their knowledge about what’s going to be intuitive or easy for them.

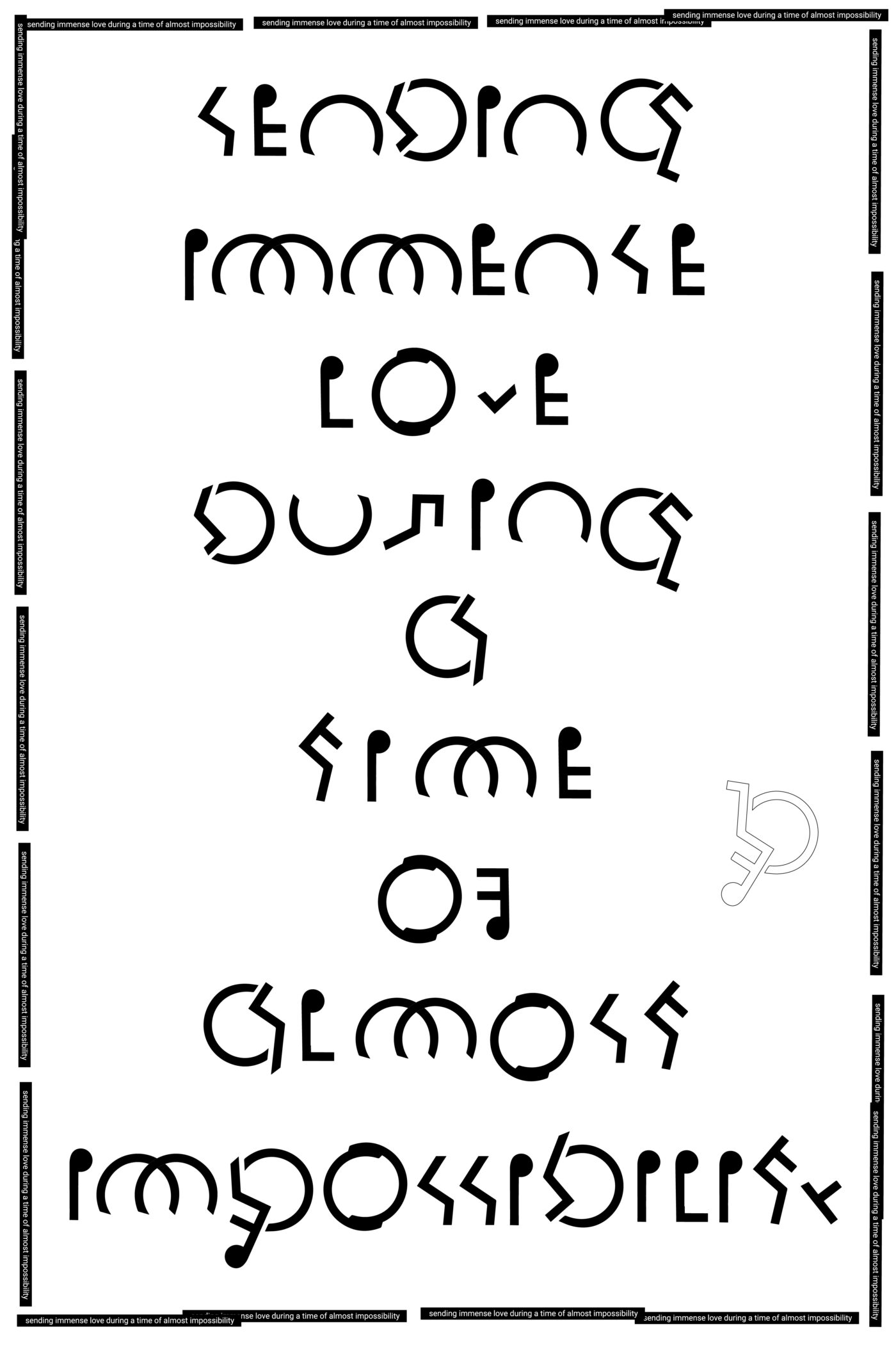

[ID: A black-and-white print featuring fragmented text reading “sending immense love during a time of almost impossibility” alongside a broken border and an upside-down International Symbol of Access. The letters are deconstructed from the iconic wheelchair figure. The border repeats the same message in a caption-like strip.]

There’s a traditional model of an artist that has to do with extreme exertion and exhaustion; I’m trying to reject that model and think about the ways that I can actually make this work as easy for myself as possible.

Ezra: As you were speaking, you were mentioning without names, other people and disabled artists. I’m wondering who are other artists making work about time or about pain that have influenced you or resonate with you that others should learn from?

Emily: Well, definitely you, Ezra. Your work is very much in line with this. Sorry to put you on the spot. I absolutely love your work. But also Joselia Rebekah Hughes — especially her writing but also her drawings. Everything, really. And Amanda Martínez. She uses a lot of repetition that is in a sense about self-soothing and connecting to indigenous patterning and histories. Also Alex Dolores Salerno. kimi malka hanauer. Olivia Dreisinger. Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo. I am fully head over heels for all of y’alls work.

Finnegan: I always find these questions so hard because there are so many people doing such amazing things. And I really do feel this sense of interdependence — in my life, and certainly in my work. I could not make the work that I make without the work of so many other people.

I was thinking about Bed Zine, Tash King’s project. I think issue number four recently came out, and I love that project. I love it as an internet gathering space. There’s an Instagram where there are posts about beds in all of their many variations and forms, and then also a publication.

Emily: Fully agree, I would be nothing without other disabled artists that I’m in community with. As a sidenote I designed one of the Bed Zine iterations with Tash, now made by another disabled designer Mia Navarro — who is also amazing.

Finnegan: It feels so connective to me… A way of being together, even as we’re very dispersed. Another person who obviously has had a huge influence is Park McArthur. Thinking about the way that Park uses material and sculpture, there’s a precision and elegance to their work that feels so incredible to me. Tonally our work is so different. My work is often very funny and goofy, but I try to hold some of the strategy that is in Park’s work.

Emily: Yeah, I can see that for sure. But I feel like there’s also a definite elegance to your work as well, though. You’re saying it’s really funny and goofy — and in some ways, yes. But it’s also confrontational in a subversive, quiet way. It slips through that barrier people put up when in a confrontational situation. Maybe it’s because part of the language is using forms that are commonplace — benches, seat cushions, clocks, etc. Maybe in part because it earnestly acknowledges what we’re all feeling — we’re all exhausted. That authenticity is so rare. Also you often make very specific decisions about design I’ve noticed, like not putting up arm rests or other barriers in the middle of benches so someone isn’t prohibited, at least by you, from sleeping there. These are quite revolutionary and specific decisions — that are then going up in public spaces, museums, and more. That takes elegance in my opinion.

Finnegan: That’s very, very kind.

I think we need to acknowledge more that life fluctuates, and we need to do what we need to do for our bodyminds.

Ezra: Thanks for that. I wanted to pull some things out from what you were both just sharing. From Fin, what you were sharing about Bed Zine being also not only a publication, which in and of itself is an amazing way for people to engage with art, but also an online community. And I know Emily, you created and manage Cripple, which also has an online presence for gathering. More recently I’ve noticed there are intentional spaces for gathering or for learning, and I know with Finnegan as well, you have worked in creating publications of different sorts.

How do you navigate building creative community artistic spaces for people in pain while also being in pain yourselves? And how does publishing enable each of you to create that in your world and also to create artistically in nonlinear ways as we were talking about time and pain?

Emily: At the beginning of my career, and as a little Emily, I had a different perspective about the world and how I should be working within it, to be honest. And part of that is that I was a product of my environment, right? Later in life I became an educator and my body started failing even faster. (I was a professor for many years. At the moment, I’m not formally tied to any university.)

And so I started to really scrutinize how I could have had a less traumatic time if certain educators or educational spaces had less rigidity with the entire learning process. And how I can be for other students, what I didn’t have, in many circumstances. If you had asked me many years ago, I probably wouldn’t have felt the same way that I do now. I’ve worked at unlearning these very ableist human-made rules. And truthfully it’s a forever process. I’m also learning to extend grace to myself about the capacities I have, which I’m better at now — but used to be very harsh about.

I was unexpectedly really sick recently and had to go to the hospital and everything. And amidst it all, I was feeling guilt for needing to step away from everything so abruptly. I was texting with artist Lu Zhang and she was essentially like, “Do what you need to do for yourself right now — there are no art emergencies.” Which is so true!

So in regards to publishing, at least, I really try to have immense flexibility. So we might talk about making something and it might fully drop off because of life circumstances — and that’s fine. Or I might be collaborating with someone and we might be working on a project for five years — and that’s also fine. I think we need to acknowledge more that life fluctuates, and we need to do what we need to do for our bodyminds. And again I’m trying, perpetually trying, to really extend that grace to myself as well.

I know you’ve collaborated on many publications, Finnegan, what do you think about flexibility and internal ableism?

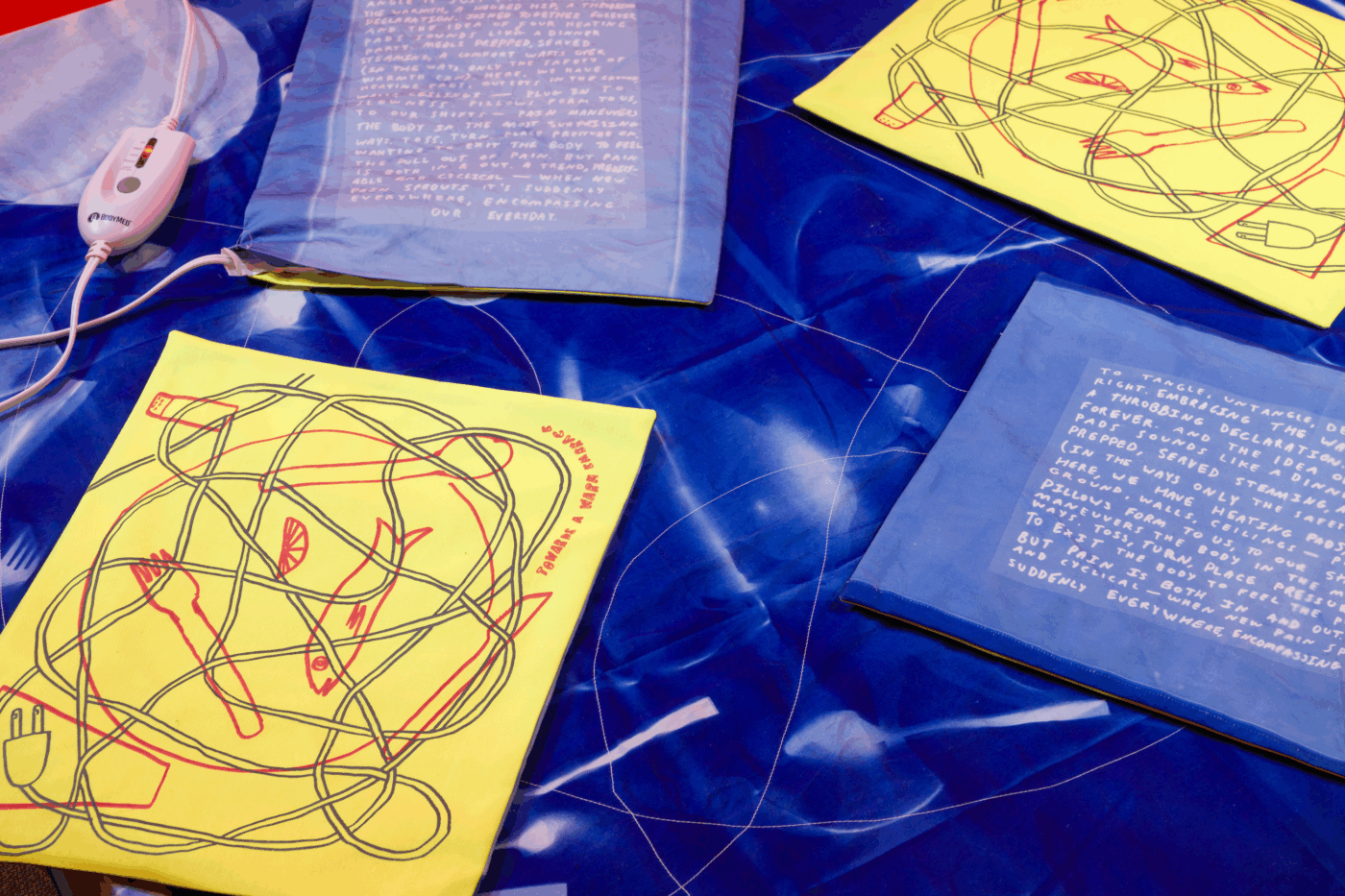

[ID: Fabric-wrapped heating pads lie on a blue cyanotype tablecloth. Some of the heating pads are yellow, printed with images of utensils, a lemon slice, salt shaker, and fish, tangled in cords. Others are blue, printed with a poem about heating pads. It starts, “to tangle, untangle, detangle, angle it just right…”]

Finnegan: I definitely relate to trying to unlearn some of these ideas around what being a collaborator is and stuff like that. Often times, that is one of the joys of working with other disabled artists. I feel like there’s this constant reminding each other and pushing back because we’re in this ableist soup all the time, and it’s really easy to forget or turn some of that inward. Having someone be like, “Yeah, there’s no art emergencies,” is like, “Oh, yeah, right.”

Emily: Agreed, I think ableist soup is the absolute best way to describe all of this.

Finnegan: My background is in printmaking. I really feel like I learned how to make through multiples, and when I finished undergrad, I didn’t have access to fine art printing spaces anymore. I got much more into things that you can do on a photocopier, or something really simple. I’ve continued to feel like self-publishing, DIY publishing, or small-scale publishing projects are so important for lots of different marginalized communities.

It feels like such an important channel for my work to reach some of the people that I hope it reaches. And this maybe goes back to what we were talking about before: sometimes I have an idea, but I don’t have the time or energy or resources to make it a thing in the world. But for me, making a zine or making a postcard or making a drawing can be a way of making the idea feel real to me.

When I first had the idea to make furniture, I was in that situation. I had no idea how one would even hire someone to build a bench. That’s how little I know about bench-building; I didn’t even know what to ask for. And so I made this simple one-page zine with drawings of the benches. And for me, so much of the work is in that. I sent those around for free to anyone who wanted them. Then hearing from people and them being excited about it made me feel like, “Oh, I want to keep working with this idea and eventually figure out how to make a bench.”

I really love the way that publications can mark a project or hold an idea even when it doesn’t feel like it can be “real” in a traditional sense. It can feel really real and solid to me.

I don’t have the time or energy or resources to make it a thing in the world. But for me, making a zine or making a postcard or making a drawing can be a way of making the idea feel real to me.

Emily: It’s funny you mention that because I’ve literally been thinking about doing a publication that’s based off of disabled artists’ drawings — of what they want to be making, but can’t — and for a variety of reasons whether it be because of lack of funds, no studio, fatigue, pain, and so forth. And by all means, someone who is disabled should do this. I’m not claiming this idea. Go for it. I love the concept of still making something in an alternative format from their ideal, because it’s still so important to put out into the world. Just because someone isn’t making something right now, it doesn’t mean that they don’t have an extreme desire to be able to make it. And that feels especially true for disabled artists who are constantly butting up against layers of inaccessibility, exclusion, and erasure.

Finnegan: Well, there is also something about the publicness of the idea. It’s cool to be able to have a way to then talk about it with other people. It also reminds me a little bit of Park McArthur’s work, her “IOU” series, which were IOUs that she would make for work that wasn’t made.

Emily: Yeah. That’s so real. And I feel that too. I have desires to do really bodily things that I cannot physically do anymore. It is kind of this schism of working between your physical capabilities and your dreams and how I wish that we could promote these dreams even more. I guess in a way that’s what Cripple functions as, as well.

[ID: A photo that has been split in half. The top is bright pink 3D test prints on top of an old wooden table. The tests are bolts, nuts, and thick chunks of pink substrate with holes. They look like toys. They are parts to sculptural work being printed by Emily Sara. The bottom half of the image is a counter at Marylous, a local coffee chain in Massachusetts that Emily Sara frequents far too often. On the pink counter is a tiny pink recycling bin, used for discarding the paper you unwrap from around straws. Next to it is a large purple dahlia flower that has been cut, resting in a glass jar. The sun is pouring through the window panes with the counter overlooking the street.]

Ezra: I have more questions, but I think it’s more important for me to let both of you ask each other questions if you want.

Finnegan: I don’t want the conversation to end without talking about treats because I feel like that’s something that we’ve really connected on. We often send each other memes or things about treats and we’ve joked with each other about life running on little treats.

Emily: Literally, yes. Right now I feel like treats are what gets everyone through everything at our current moment in this world.

Finnegan: I was thinking about that in relation to the topic of pain, the little treat as a coping tool, a moment of joy or relief. And so I wanted to ask you what some of your recent treats have been.

Emily: I’m so appreciative that you asked that because I love talking about treats. As you know. [laughs]

One of my treats is coffee. There’s a coffee shop called Marylou’s that’s a very local thing in Massachusetts and everything about it is a very specific pink. I find it funny because one time it just kind of clicked — I’ve had pink hair for many years now, but I was standing in there one day and I’m like, “Ooooh, I get it.” [laughs] Because everything is pink. I had on a pink dress at the time, and my hair is a fluorescent pink. It just brings me so much joy to see color. I’ve found I also have a strong reactivity to color — it’s important to me and my work.

I think my other treat is that I draw a lot at night on my computer, at the very end of the day. My bed drawings. They feel like a release — they’re very chaotic and personal. What about you?

[ID: A tableau of objects on top of the mini fridge. A handwritten sign says “Have a seltzer” below a crossed-out-stairs icon. A fake plant. Needle-pointed coasters with a stair motif. A thumbs-up-shaped container filled with Smarties candy. A large vase holding Nerds Ropes. The book No Right to Be Idle: The Invention of Disability, 1840s–1930s by Sarah F. Rose.]

Finnegan: I am really enjoying the image of you in all pink, in the all pink coffee shop, getting your coffee treat. I’m a big candy treat person. My favorite candy is Nerds Rope, so that’s a big one for me. I’m actually looking at my desk right now, and I have a Blow Pop and another lollipop. And then similarly with coffee, I feel like I have a hard time remembering to drink water and stuff like that, so any type of treat liquid that I can get into my body, I’m all for it.

Emily: That’s awesome. I’ve never tried a Nerds Rope. Definitely going to now and I’ll report back! My question is what are some things that you wish you knew at the beginning — the advice that you could give to your earlier self? I know that’s such a generic question, but I think it’s actually so critical, especially in our realm. One of the reasons why I started Cripple was because I feel like we don’t have proper archives of these resources for other disabled artists — to see themselves in other artists.

Finnegan: So many things. One I think about a lot is that when I was growing up as a disabled kid, I received the message that disability needed to be as small a part of me as possible. That’s what would keep me safe. And I honestly feel like I’m always in the process of trying to let go of that and allow myself to be fully who I am.

I feel that to the extent that I have been able to do that, it is because of the work of other disabled artists, writers, and thinkers. That’s part of why I feel really excited about thinking about disability culturally — and obviously defining “disability culture” is an impossible, giant, unending, nebulous thing and that’s what’s fun about it and the point — but for me, starting to understand some of the ways of making and being that come out of disability has helped me feel more rooted in myself.

Emily: I love that. My other question is what are some things that you wish you could change in regards to art and disability? If you’re speaking directly to the people who can be making those changes — what are some things that you believe would help future disabled artists?

Finnegan: One that’s constantly on my mind right now is COVID risk, and ways that I feel so heartbroken by how some of the strategies we learned around masking and air purification and checking in with each other and having conversations are going away. I often feel like I’m coming into spaces being the one who’s like, “What’s the plan? What’s going on?” And wishing that was something that became more built into the ways that we do things and the ways that events are planned, and similarly, having remote gatherings and things like that, I think.

Emily: Yeah, agreed. I’m always thinking about how I would really love to develop the right opportunity — to bring so much of the support, access, and work that happens with Cripple — but in a physical space. And being actively, very conscious of people’s very specific support needs.

Also as a side note — now that you’ve told me about Nerd Ropes as treats, I’m really sorry if in my automatic, penguin-pebbling nature, I get you far too many of them over the course of our lifetimes. It’s genetic. [laughs] My mom does the exact same thing — she once mistakenly thought my cousin loved whoopie pies (from Marylous of course) and bought him so many over the years — she would even mail them to him when he went to college. He now of course can’t stand the sight of them. Ugh, life is funny. Everyone is forewarned, don’t tell me your favorite treat.

[ID: A portrait where Finnegan Shannon is holding a Day Clock in front of their face so it sort of stands in for their head. The clock shows only the day of the week, not the hour or the minute. It obscures most identifying info about them, though they think you can still tell they’re a white person from the color of the skin of their hands. They’re wearing a loose sweatshirt and pants. A pop of blue from their socks. They’re sitting in a plaid armchair. Armchair, rug, plants, and thrifted side table cozy up the studio vibe a bit.]

Finnegan Shannon

They // Them // Theirs

Brooklyn, NY

Finnegan Shannon (b. 1989, Berkeley, CA) is an artist experimenting with forms of access. They intervene in ableist structures with humor, earnestness, and rage. Some of their recent work includes Alt Text as Poetry, a collaboration with Bojana Coklyat that explores the expressive potential of image description; Do You Want Us Here or Not, a series of benches and cushions designed for exhibition spaces; and Don’t mind if I do, a conveyor-belt-centered exhibition that prioritizes rest and play. They have done projects with MUDAM Luxembourg, the Queens Museum, moCa Cleveland, the High Line, MMK Frankfurt, MCA Denver, and Nook Gallery. Their work has been supported by a Wynn Newhouse Award, an Eyebeam fellowship, a Disability Futures Fellowship, a United States Artists Fellowship, and grants from Art Matters Foundation, Canada Council for the Arts, and the Disability Visibility Project. Their work has been written about in Art in America, BOMB Magazine, The Believer, and Out Magazine. They live and work in Brooklyn, NY.

finneganshannon.com

Instagram: @finneganshann0n

[ID: An image taken from a video still of Emily Sara. She is a white femme, gently smiling with oversized brown tortoiseshell glasses. Her hair is about shoulder length and it is electric pink. She is wearing a black dress with little flowers on it and a few gold necklaces. She has a scar across the front of her neck. In the background is a pink and green swirl, a blurred background.

Emily Sara

She // Her // Hers

Massachusetts

Emily Sara is a queer, disabled, neurodivergent, artist, designer, writer, and alt educator. Her interdisciplinary practice spans a range of media and mediums, centering critiques of the Medical Industrial Complex (MIC) while also cultivating support and mutual aid among disabled creatives. She is a 2024 Disability Futures Fellow, and an inaugural 2025 Eames Institute Curious 100 honoree. Emily’s work has been featured by institutions including Boston Art Review, Carnegie Museum of Art, Hyperallergic, Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, MoMA, Printed Matter, Victoria & Albert Museum, Yale School of Art, and more.

Emily founded Cripple, a publishing initiative that supports disabled artists and designers. Cripple organizes events such as the series “Fine, We’ll Just 3D Print Our Own Wheelchairs (And Other Mobility Devices)” and champions a non-linear approach to collaborations and distribution. She is also the originator of Stim Aesthetics, a theoretical framework that explores the significant influence of disability and neurodivergence on contemporary art and culture.

Alongside her practice, Emily needs a service dog, is going to too-many-but-necessary doctor’s appointments, searching for a wheelchair-accessible van, attempting to keep her chronic pain at 7 out of 10 or lower, dyeing her hair flaming pink, and staying alive.

emily-sara.com and cripple.info

Instagram: @emilysara12345 and @_cripple_