Falling

Apart

in

Half Time

“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” – Octavia Butler

4–5 minute experience, or the time it takes to peruse a photo album.

Touch and pressure are inherent qualities in printmaking. What you touch and what you pressurize are literally visualized through materiality. The resulting impression is a newfound narrative — a print is born out of a visceral journey! Here, Benjamin Merritt guides us not only through his process, a self-directed way of making and discovery, but also its outcome in the form of two new works. By moving us through his prints and process, we cannot help but feel what is being formed and informed again and again, right there — be it in material or be it in language.

BY BENJAMIN MERRITT

When I am making a print, I practice writing the words over and over again until the motion feels natural, and then I continue writing it backward until that feels natural. After I get the feeling in my hand, I write the words backward on whatever matrix I am using to print with and I exaggerate the letter forms: extending the curve of an e too far, dragging the end of a t downward. The handwritten forms with their long, awkward shapes represent an exaggerated self that exists through the choreography of writing, shaping the self through repetition and reflection.

The choreography of creating letterforms in my prints is a mirror of the similar choreographies that push the body through illness. When we are ill, we constantly learn how others have navigated similar situations and we try to learn the right steps to help us continue living in our bodies.

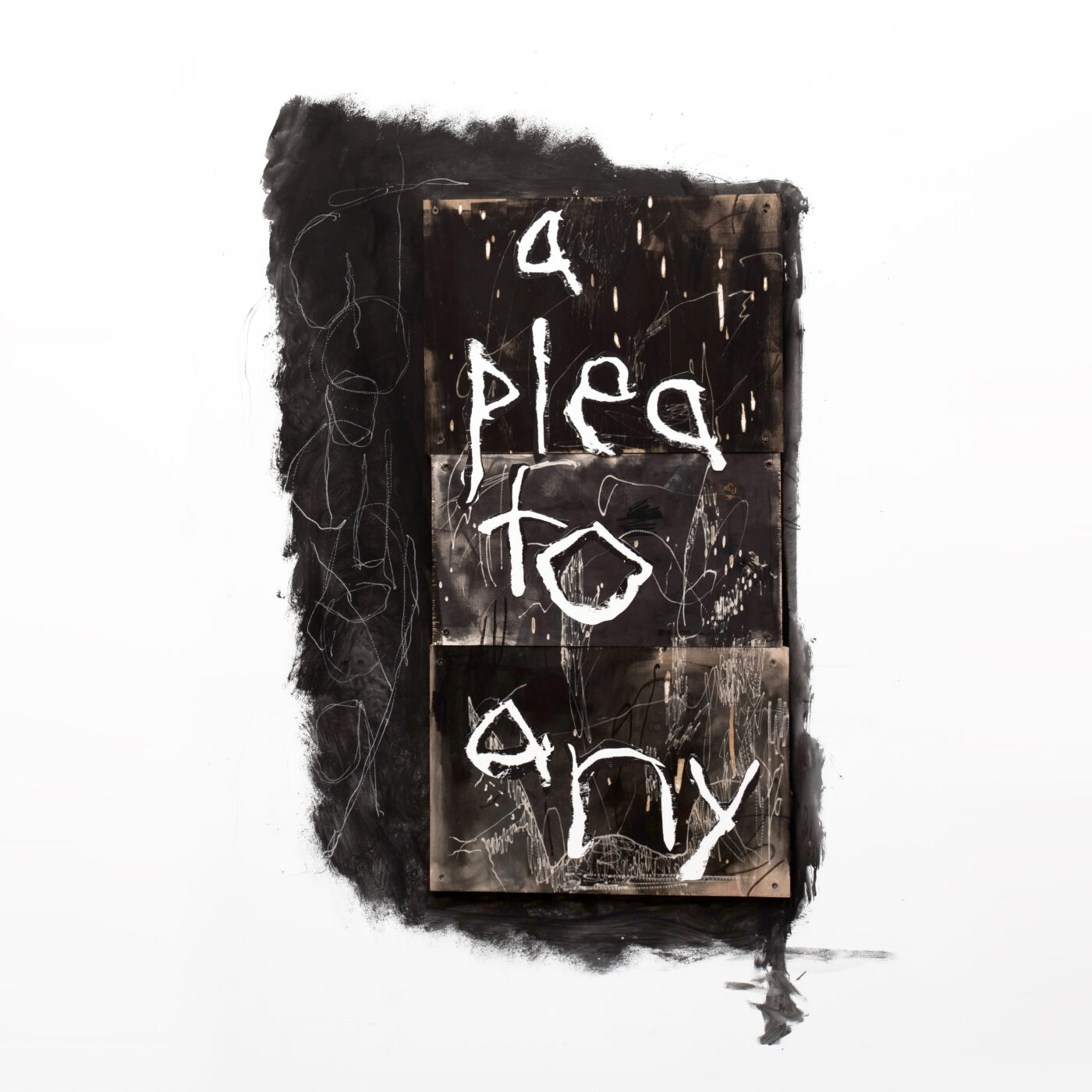

[ID: Image of handwritten text reading “a plea to any” in white against an asymmetrical dark background. The background is layered, and the edges of three pieces of paper peek out through paint which shows the texture of the brush at its boundaries. Other letter forms are scrawled in white around the edges like graffiti.]

Often the choreography of sickness is learned from difficult traditions, passed on to us through language.

Often the choreography of sickness is learned from difficult traditions, passed on to us through language. We follow guides given to us by professionals, written down on medical labels, as advice on forums, movements passed through “verified” sources on how to navigate a body in pain — all through “objective” language. After some time it becomes nauseating, our bodies moving in ways that are unnatural to our sick bodies, attempting to conform to a prior notion of healing that very few have found to be true.

After years of experiencing this choreography and type of language, I started to primarily use words in my print work. I found a liberating quality in the looseness of language, something that is inherent to language but frowned upon in the clinic rooms where the most intimate parts of myself were being talked about. The things my body experiences can be described accurately in a thousand different metaphors, but not in a numerical scale. I learned that the non-objective way of using language was the most fitting for my body, that using language is a dance itself. We describe things over and over again incorrectly, until something fits.

[ID: Left image: Installation image of a three-dimensional artwork composed of three sections that jut out from the wall. Each section contains two large pieces of paper stacked on top of each other, covered with textured paint, marks, lines, and hand painted words. Center image: A close up on one side of the artwork, dominated by the words “a burial gift” drawn in black. Other words are layered underneath this text in white and markings and scribbles surround the space. Right image: A photo taken from the right hand side. The words “or just bad luck” are stacked on top of one another against a backdrop of scrawled lines and smudged paint. The words “trying to find what is left behind” appear to be scratched into the paint of the bottom of the central section.]]

In printmaking, and with language, we never get things right the first time. I think that’s true in sickness as well. I go through times where I think I’m pretty good at being sick — in that I’m able to manage a body of constant interruptions and feel that I can follow the lead my body is giving me. Whenever I feel that I’m getting better, something changes drastically, and I have to rehearse again. I’ve learned that being sick is very similar to my practice of creating letterforms and experiencing language; it’s about constant rehearsal, messing up, exaggerating the self in order to gain perspective on what’s happening.

Rather than dancing with the choreography of sickness that we learn through the strict medical definition of healing, I am trying to learn choreographies from my sick friends and through rehearsals and practices of language — changing how healing is defined, rather than sticking with the tradition. It’s a group dance that we’re told to learn as individuals, but once we rehearse together, we ease our way into choreography of healing. We have to mess it up a few times before we get it right.

[ID: Benjamin, a white person with shoulder-length hair and glasses looks into the camera. He is wearing a Fugazi tee shirt and his cat is sleeping behind him.]

Benjamin Merritt

He // Him // His

Minneapolis, MN

Benjamin Merritt is a printmaker and writer seeking the healing qualities of elastic language. Merrit’s work, largely exploring the intricacies of chronic illness and disability, creates a space for language to pull at our experiences of sickness and make them more visible. His work is influenced by literary theory as much as it is influenced by emotional hardcore, otherwise known as Emo. As a child, Merritt copied drawings from the liner notes of Emo CDs, and the grimy and melodramatic aesthetic has become fundamental to his printmaking practice and expression of language.