“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” –Octavia Butler

5 minutes, or the time it takes to find a book in a library.

In his most recent film, artist and filmmaker Angelo Madsen draws from the personal archive of Fakir Musafar and interviews a constellation of queer elders in the body modification movement. Madsen intentionally avoids trite conclusions, carefully excerpting and collaging an entwined portrait of Musafar and his community. In the following reflection, Madsen draws from his recent experience making A Body to Live In to enumerate the challenges of working with archival material, and the importance of wrestling with them anyway.

BY ANGELO MADSEN

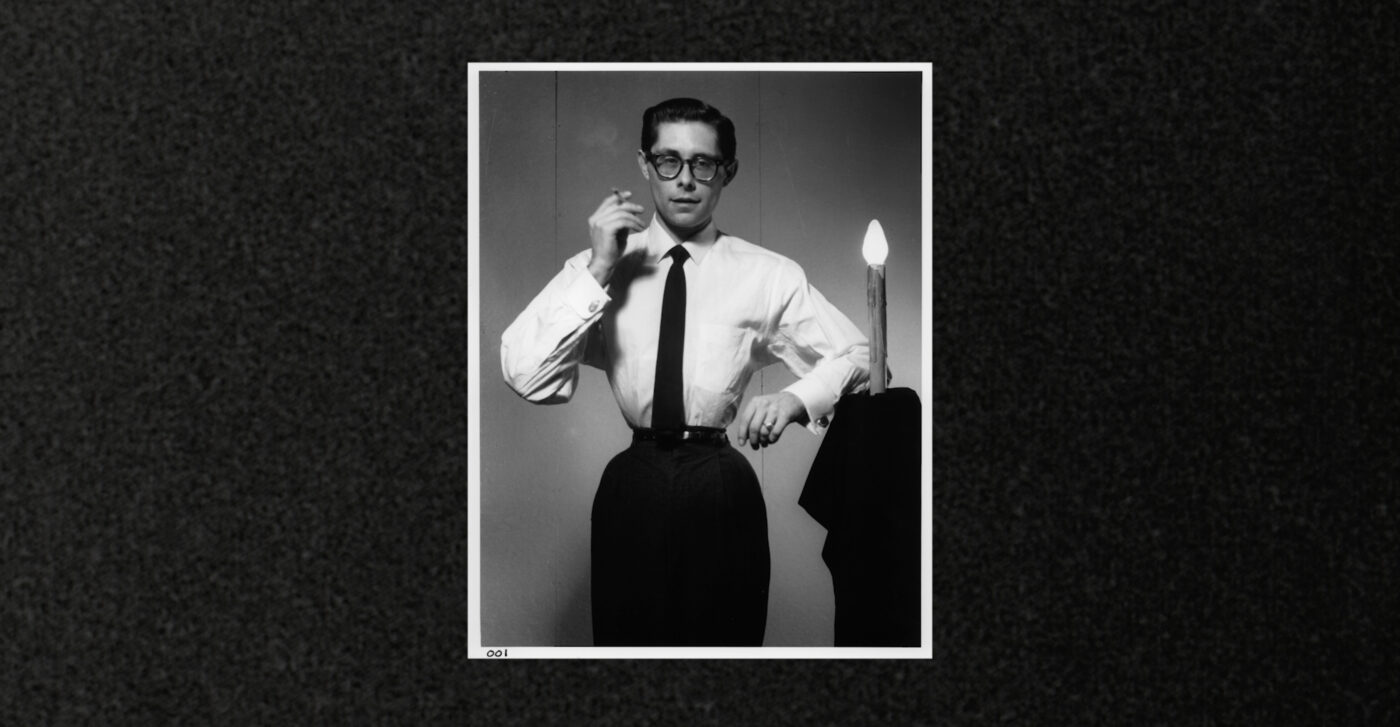

[ID: A black and white archival photograph depicts a man in business attire with his waist dramatically cinched. He smokes a cigarette and leans against a large candle on a table.]

My relationship with the archive, as both a thing and an idea, is complicated. As a big nerd and someone who makes projects with and about archives, I want to tell you about how rich they are as a site of exploration or how important it is to preserve our histories. But I think my troubles with the archive are more compelling.

For me, the act of archiving inherently declares:

A sense of importance, which I am suspicious of in general.

Archives are not keepsakes or memorabilia. They are investments in the future of their owner or originator’s existence. An archival object says, “I declare that this will be essential to someone’s research in 50+ years.” A sense of importance controls whose history will be preserved, even within the most marginal of contexts.

A commitment to materiality, which I also question in general.

I don’t want more stuff in my life, whether it be material or not. Our brains and bodies aren’t cut out for this level of consumption of seemingly unlimited access to material and non-material input. The age of “keeping” is over, apologies Gen X.

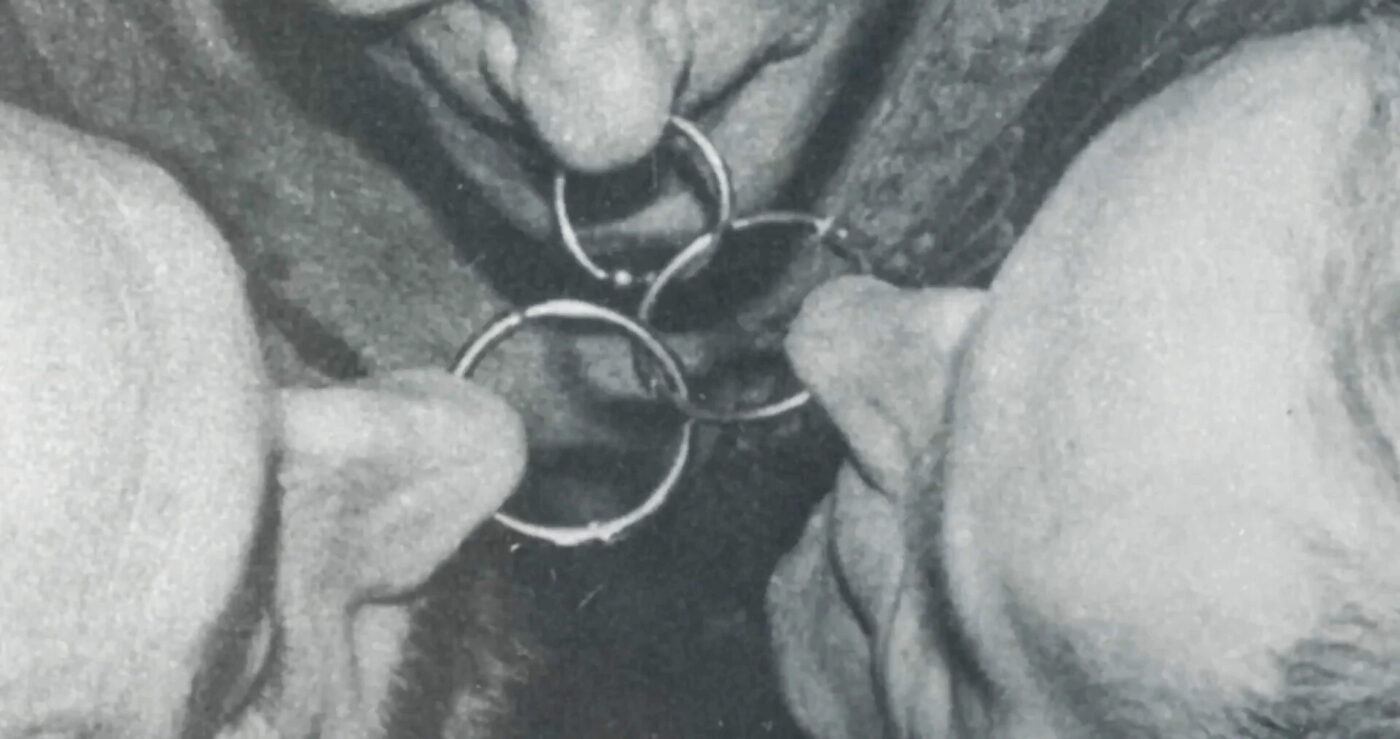

[ID: A close-up black and white shot of three men, taken from above, with their septum piercings interlinked.]

Archiving implies a future wherein one will be able to sift through materials at their leisure. It is an imaginary based on the present moment.

Even as our world is being dismantled nut by bolt by political regimes and climate change, we still in some distant imaginary see someone sitting down in a library that looks very similar to ours and sifting through photographs of something from decades earlier. We can only imagine a future based on the present. This idea is one of my favorite sci-fi concepts, which is why Logan’s Run will always look like 1976 even though it takes place in 2274.

Once the original owner of these materials is dead, there is no more consent.

Do I want someone reading all of my personal letters in one hundred years? No. Do I want someone to be able to see all the heinous drafts I went through to get to something decent? Maybe, maybe not. Luckily, this will not happen to me because I don’t keep anything and I’m not that important.

[ID: A sepia image of a photograph of a chest with a hazy, abstracted projection atop it. The chest is adorned with piercings and jewelry. ]

My most recent feature film, A Body to Live In, is almost ninety percent archival. In the edit process, Would this be what Fakir wants? was a constant question for me. By extension, it was important to listen to the wishes of his partners. I don’t make “takedown,” exposé, or revelation work — it feels unjust in my mind and body — but I also don’t make work to glamorize anyone. This middle ground is murky though, especially in a post-truth world where our hyper awareness of the myth of objectivity can actually derail the necessity of objective truth. I come from somewhere and I bring that somewhere with me when I make work, but I still find my ultimate goal is to stay truthful and objective. This might be the only instance where I feel like striving for utopia is a helpful framework. The dance between following wishes, considering subjectivity, and staying true to the material is where I find this work really exciting.

At the same time, I am fully aware that dissecting the dimensions of archival filmmaking does nothing for our everyday lives; however, the archive itself does. The archive creates a window into a past we did not experience, to show us how people managed to survive through whatever crap the world was throwing at them at that moment in time. And ultimately, it makes us feel less alone.

Jenni Olson likes to say that nostalgia will save us. I don’t know if it will save us, but I do know that we need history consistently brought into our present-day awareness, not only to not repeat mistakes, but to remind us of our own humanity (and inhumanity).

[ID: Angelo, an artist standing on a sidewalk next to a busy city road, is posing casually in the sun. He is wearing an all black outfit with a black baseball cap. A white fabric patch with a purple feminist symbol print is sewn to the front of the cap.]

Angelo Madsen

He // Him // His

Burlington, VT

Angelo Madsen is a multi-disciplinary artist, filmmaker, and educator. His projects consider how human relationships are woven through personal and collective histories, cultures, and kinships, with specific attention to subcultural experience, phenomenology, and the politics of desire. Madsen’s works have shown at the Berlinale, Sundance, Toronto International Film Festival, New York Film Festival, Tribeca, De La Warr Pavilion, MCA Chicago, REDCAT, Museum of Moving Image, and dozens of documentary, LGBT, and experimental film festivals around the world. He is a Creative Capital Fellow (2025), a United States Artists Fellow (2023), a Guggenheim Fellow (2022), and has participated in residencies at Yaddo, MacDowell, Pioneer Works, Headlands, Skowhegan, Bemis Center for Contemporary Art, and others. His film North By Current (2021) aired on POV (PBS), was nominated for an Independent Spirit award, and won the Cinema Eye Honors Spotlight award and IDA’s Best Writing award. Madsen teaches at the University of Vermont and lives between Burlington, VT and New York. His friends call him “Madsen.”

Single channel film and video works are available from the Video Data Bank (various titles), Outcast Films (Riot Acts), Grasshopper Film (North By Current), Mubi (One Night At Babes), and The New York Times (Stay with me, the world is a devastating place).

angelomadsen.com

Instagram: @angelomadsen