“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” —Octavia Butler

25-30 minute listen, or the time it takes for a midday stretch.

![]()

A CONVERSATION WITH TARA KANNANGARA AND ROSÁNGELA PÉREZ MOLERO

For Tara Kannangara and Rosángela Pérez Molero, music-making is an act of translation, a sonic rendition of the messiness and joy of daily life and communal existence. Kannangara and Pérez Molero create work by first attending to their inner lives and emotions, and then immersing themselves in collaborations with people they trust and enjoy spending time with. In this conversation, they discuss the importance of personal writing practices, abandoning unhelpful labels and toxic teaching methods, and embracing your own values and processes as a bandleader.

Jessica Ferrer: I’m curious about how often both of you rely on writing like the kind you did for M³ (Mutual Mentorship for Musicians)’s Anthology as a form of self-expression or self-discovery.

Rosángela Pérez Molero: I rely on writing in different forms. What I did in the piece for the Anthology was a mix between two dimensions of my writing. It’s related to poetry, this intimate space where I enter when I’m trying to comprehend the contradictions of my existence, because I think poetry is perfect for exploring that. And, on the other hand, because I am also a music therapist, I am also really used to writing in academic ways. I love that because through that [form] I get to build ideas, destroy ideas, understand paradigms; it’s my way of communicating my ideas to others in a way that can be more functional. It’s something that I often do in my daily life. But yeah, as I said, it’s this combination between the playfulness and the power of contradiction that you can find in poetry, mixed with the functionality from academic writing.

Tara Kannangara: I write often but usually, I’m writing some forms of nonsense because I have a very hard time. It takes me quite a while even though I’ve spent a lot of time in academia. It’s a slow process but I’ve learned how to enjoy the process because it is exciting to mine really simple ideas. The everyday nonsense I write are usually the truths about the day. I like to start with something small and then expand it over a long period of time. Pretty long, actually, because then the idea has a bit of a life cycle. It starts as this thing and then it becomes another. But what Rosángela said about the idea of exploring contradictions and destroying the idea, in essence, is also so fun. When you have enough time with an idea, when you can actually destroy it, it’s incredible. It’s an incredible feeling, very powerful. So yeah, I really do love to write but that’s the most formalized that it ever looks these days.

What I’m trying to say is that when we are playing instruments, we don’t have to stay only in this little part of the sound spectrum with the “musical” notes. We can play with other ways of feeling sound.

Jessica: Rosángela, one of the lines that you have in your piece has stuck with me, and it’s this little equation, “Sound ≠ Note.” I would love to know how you define those two terms, and why it’s important to not equate them from your perspective with one another.

Rosángela: First, let’s imagine that we are walking on the street in front of my house. The soundscape will probably be noises from cars, dogs barking, footsteps, maybe your own breathing, maybe some people talking, right? That’s our daily life with sound. In that scenario, you probably wouldn’t find any musical note we consider a musical note, which has controlled, fixed pitch.

What I’m trying to say is that when we are playing instruments, we don’t have to stay only in this little part of the sound spectrum with the “musical” notes. We can play with other ways of feeling sound. In the street, you can make relationships between sounds based on other things that are not pitch, like the grain, color, density, form, attack, volume, ending, a bunch of options that we can borrow and use in our exploration and in our daily life with our instrument. It’s important to understand that notes are only a fraction of the whole spectrum of sound.

Tara: I just love that idea. I think most people want to codify or label or create a hierarchy when it comes to anything. It happens with sound, notes, pitches, and music. The way people decide to even use Western notation; how that’s seen as some kind of show of education. The idea that it’s only just one piece of the pie is really liberating, and it makes you want to explore other perspectives, especially when you come from an institutional setting.

When you’ve studied music for a very long time, you have a tendency to want to stick to those systems and hierarchies, in a way, just because they kind of validate our work. But if we didn’t need that validation, what could it be? Do we need to say it’s a note? Do we need to say it’s anything at all? Being able to let go of the labels and the naming of things, I think, is really healthy, and then you just get to hear in a totally new way.

Being able to let go of the labels and the naming of things, I think, is really healthy, and then you just get to hear in a totally new way.

Jessica: In your writing, Tara, I resonated with the anecdote about using humor or jokes to downplay harmful experiences, and then finding yourself unable to process or move past them, even though you’re trying to. I think you’ve talked elsewhere about wanting to create from a place of joy instead of tragedy. I’d love to hear more from you about how you tap into those joyful spaces.

Tara: Yeah, it’s changed for me a lot over the past few years. If I were to distill it, I want to be in places where people want me around. Sounds simple, but it’s not! For many years I was trying to make myself belong everywhere. I was trying to change and manipulate myself. Every aspect, whether it be how I looked, how I spoke.

In a lot of those spaces that were never really built for me from the ground up, I always felt like I was missing this one little thing that I had very little control over. It always made me feel like, “Oh, I’m just not good enough yet, I haven’t learned this thing yet, I always have to keep striving.” And then you start to believe there’s some nobility in it, that we’re these imperfect people, that we should just strive for greatness, and take criticism that could be really harsh, or mistreatment, or if we’re going to go further, abuse. I was just used to taking a lot of it on.

Now I only play shows with people I feel comfortable around, people who I feel align with me ethically. I really think a lot about that. Before I was just like, “Oh, they’re kind of weird, but I guess I should take any opportunity I can.” Now, I’m very specific about where I interact and where I give my knowledge, where I receive knowledge. I’ve just gotten so specific about it and because of this, I’m way happier now. I’m happy all the time when I make music. I am because I trust everyone involved. And M³ was really great for that, because that was a really positive space with extraordinary humans that are doing such important work. It was a challenge, too, so to have all of that happen and still be happy? It’s a great thing. It’s a revelation.

Rosángela: For me, that is always the first step when I‘m deciding if I play with certain people or in certain projects. The first step is [making sure] I like these people, I resonate with these people and their souls. It’s the first thing because I need to be able to communicate with them on a deeper level than I usually do. And in order to do that, I need to be aligned.

[ID: A black and white image of Tara performing with her bandmates onstage while a camera crew films them.]

Jessica: When you are in this mode of composing for music specifically, where do you start? To borrow terms from writing, what are the editing and revising phases like and when do you know you’re finished?

Tara: Well, I used to notate everything, and now I don’t notate anything. If I’m working for other people, like when I teach a class and they submit work to me, I usually ask them to submit the chart that’s notated. For my own music, I make my band learn everything by ear. It’s just how I’ve decided to do it, because the music is simple enough. It’s all about taking it in aurally. And once it’s in there, then all the work begins.

It’s like when we’re in the room together, and we can play it, it’s not just playing. It is the first step, and then the next step is, how do we feel about it? And then we kind of arrange as we go. We talk about what these things mean, we return to the lyrics and we’re like, does that even make sense for what this word means? It’s all conceptual, it’s not about execution anymore. I don’t really care if people are playing it perfectly. That is the least of my concern. It’s about capturing an essence. It’s an exciting place to be because we just become a group of thinkers, deep divers.

I think it’s really hard to know when something’s done. I know when something is done when I play it for people out loud, when it’s not just for me and my band. I play it at a show and then I can tell. I let it live outside of me at least a few times before I know something’s done. That’s my process.

I love graphic scores. I think they are more accurate to what I’m trying to say because they give the performer a way of moving in space, which is much more important than the notes.

Rosángela: I love that. I want to be in your band! I mean, what you said about capturing an essence, I resonate with that because the composition begins with the perception of my need. Then, this need transforms or embodies a concept, and I start this translation work, which can be with notation or without it.

I also tend to work a lot with maps and graphic scores. I love graphic scores. I think they are more accurate to what I’m trying to say because they give the performer a way of moving in space, which is much more important than the notes. I care about how you’re going to move with that sound, how you’re going to work with me and my sound, and so I use different notations for that. Sometimes I work with a traditional notation, but only if I feel like the concept is naturally flowing that way.

As Tara was saying, when I work with other musicians, I am interested in the collaboration. It doesn’t matter if it’s my composition, I want to see what they can bring to it. And so the ending process you’re asking about is when I am in rehearsals. All the time changing and playing again, that’s the process.

I know it’s ready when I stop listening to the decisions behind [it] and I start feeling the experience. In that moment, I know the music is ready because it’s working on me as a listener, too, and not only as a composer.

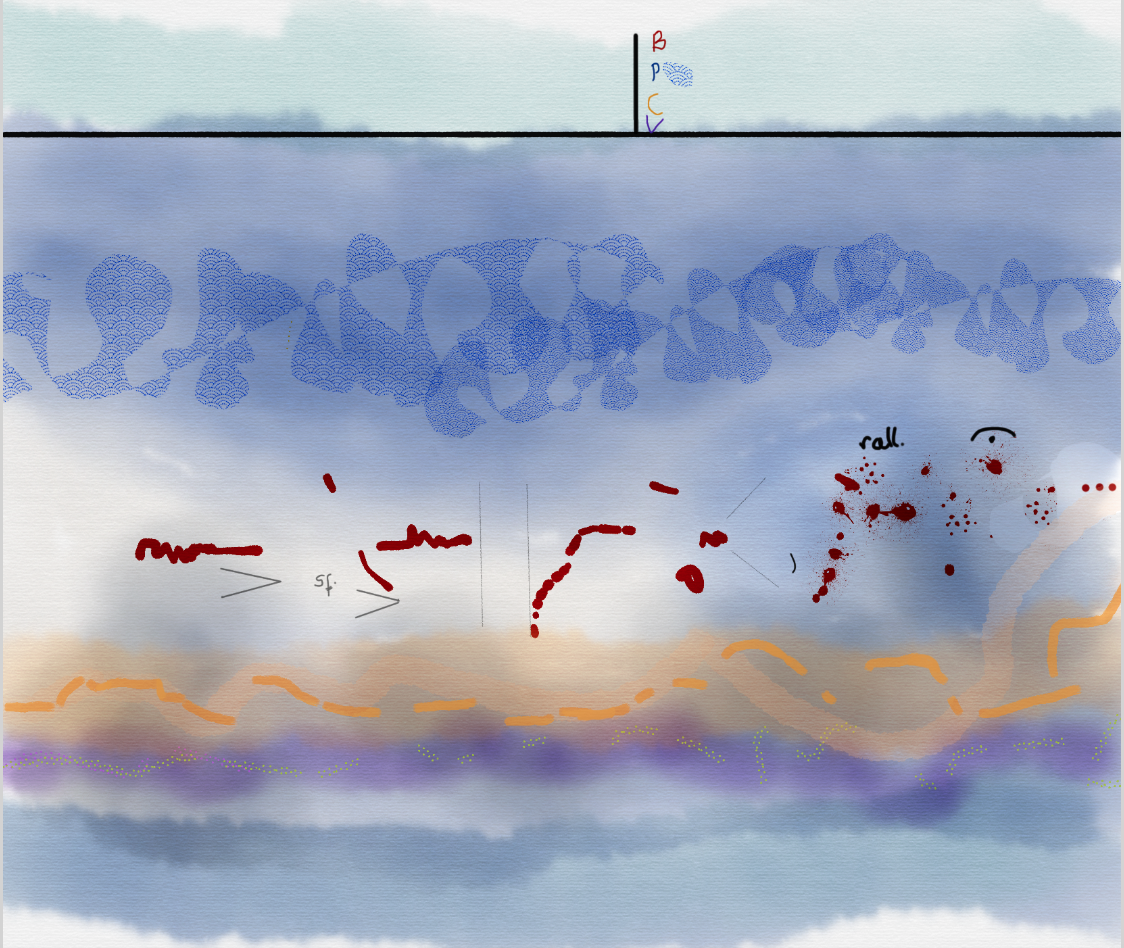

[ID: A digital painting predominantly in blue with touches of red, violet, and yellow containing lines, textures with a watercolor look.]

Jessica: It’s funny because I think in other conversations in this New Suns space that we’re cultivating there’s a lot of talk about pushing against ideas of mastery or virtuosity. I’m getting the sense that it’s something this field really grapples with a lot. What’s the hang up with mastery? Why can’t we let it go in the way that you seem to have articulated so beautifully, of letting go of the particulars of execution in favor of just showing up fully?

Tara: I think you’re very right. It’s just, you know, there’s so much study. A lot of musicians I know, they all went to school or have been playing music since they were kids. Many of them decided to go past high school into post-secondary studies, and studied classical music or jazz. It’s music that’s now taken care of and cultivated in institutions versus outside where I think people used to do it. People still do [it outside], but it definitely happens a lot in university.

In some way, mastering something, or the idea of feeling like you could, gives you a sense of safety. It’s like, well, if I can get good at this, I’m untouchable. I’m impervious to criticism. But being impervious is not good in the arts. I think vulnerability is good in the arts. If we can express our vulnerabilities in a safe way, we can usually have these incredible breakthroughs in art and music. We can get further with our instrument when we decide to be vulnerable instead of just trying to smooth out all of the edges.

We can get further with our instrument when we decide to be vulnerable instead of just trying to smooth out all of the edges.

Showing up as someone who’s really incredible at their instrument is only one piece of the pie or puzzle. It has very little to do with how good I am as a musician. Also, you’re just chasing something that doesn’t really exist. Even the people that I would consider masters, I think they’re always looking for the next hurdle to jump over. The amount of pressure we put on ourselves — I feel it’s the ego, where we either think we’re the greatest or we’re the worst. We do these massive swings when there’s actually this really beautiful egoless place right in the middle, where we can walk this middle path and observe from that middle path when we’re achieving or when we are falling short of what we want to do.

I’m happy to let go of the mastery thing. I have so much more time now to do things I care about. I can laugh, cook, be with my friends, and see my mom and dad, all these things that exist and are so incredible. They’re so fulfilling. I want to do those things, too.

[Learning technique] is chaos, it’s great, but it’s only part of the spectrum of being an artist because — and this is so important to me — it’s like you are learning the technique before feeling the need to develop the technique.

Rosángela: It’s a question that is not really about music. It’s about colonialism. It’s about paradigms that are foundational: rational thinking and Western culture. It’s also about the wounds of humanity. We are trying desperately to say we are good enough. And so we create these systems that can tell us that we are good enough, and we claim that they are objective. Obviously, they are not. So on one hand there’s that.

And on the other hand, we are wired with this sense that technical mastery is the most important thing in life. These mastery standards are linked to the players. I could say interpreters, but to be able to interpret you have to foster your inner self, and you need time for that, as Tara has said. You need to live. You need to feel. You need to sense. [Learning technique] is chaos, it’s great, but it’s only part of the spectrum of being an artist because — and this is so important to me — it’s like you are learning the technique before feeling the need to develop the technique. It’s super weird because it’s backwards.

It’s a huge conversation because we keep thinking that this is the [only] way, right? As Tara has said, we live in institutions that are worried about us being enough, but not about us being creative, you know? It doesn’t matter to the institutions if the people in it are happy with the things they are doing.

So for me, it’s about understanding that this is a conversation that includes and reflects on our values and the rest of society. They’re not functional anymore to us as artists and that’s probably why you were saying that you have heard this a lot lately. Something has to change. In these times, what we have to offer isn’t about mastering technique. It’s not about that. It’s about something else. But this is a question for all the disciplines in the world, not only us.

Tara: That was the best answer ever! I was so captivated, oh my god! I just have to say, I was on the edge of my seat. What you said about developing the technique before feeling the need to develop the technique is one of the most beautifully articulated phrases about institutionalized music. It’s like, “Why do we even do it?” We don’t even know why.

[ID: Rosángela seated playing violin with a look of concentration on her face. She sits in a warmly lit room in front of a music stand.]

Jessica: I want to pivot toward sounds that are cultivated in community instead of in institutions. It’s very apparent to me now that you’re learning in a lot of spaces that aren’t institutions. Are there any recent or very memorable experiences that you could share about?

Tara: Well, there are a few things. The first thing that I really love to do is this writing class taught by my friend. We’re all musicians in this class; we just show up and we do writing prompts for fun. I guess we are getting some collective knowledge out of it, but we play games and there’s no specific goal in mind. They’re just writing prompts to stoke the imagination. For so long I was taught that everything’s an opportunity, and you have to cultivate each idea to the end. Sometimes you can let something out and just let it be what it is, and it doesn’t have to mean anything or contribute to the bigger picture. It could just be letting off some creative steam in a place that feels really right for me.

I also notice that I’ve been feeling really overwhelmed by how wonderful my friend group is. We played a show recently at a festival, and we had a lot of time off, and I remember we just sat on the grass, we played cards and dice, and just sat there and talked about our lives. I love the art that we’re making but it’s so much more informed by these really quiet moments, these vignettes in my life, that for a long time I felt were interludes to the moments where we played. Some of the most artful moments of my life are when we are just having dinner together.

Rosángela: I like your honesty. I think most people I know feel that way, where it’s like we’ve already rehearsed, but do you want to talk? Do you want to hang out? And it’s like yeah, that’s the deal!

Improvisation is a great way to connect with life and be with others. I remember a great friend, a guitarist. We were in rehearsals and before we started I said to him, “I don’t know where my head is, I don’t know where to play.” He said, “Let’s just play.” And so we began this kind of ritual before rehearsal where we played for a couple of minutes and tuned ourselves to be able to really enter this other space.

Improvisation is a primary need in my life, and I could do it alone, but with other people it’s amazing. My sound is going to change through what others are bringing to the conversation, and I am best able to listen because I don’t know what’s going to happen. My motivation is to really be there, drifting together. It’s the most relatable feeling to living because we love to think that we know what we’re doing, but no, we are drifting all the time. Improvising with others is a way to be in love with everything.

My motivation is to really be there, drifting together. It’s the most relatable feeling to living because we love to think that we know what we’re doing, but no, we are drifting all the time. Improvising with others is a way to be in love with everything.

Jessica: That feeling of fun, the image of drifting together and not feeling adrift by oneself, I think, is beautiful and should be embraced more readily. We’re coming up near the end of our time, and I just want to check and see if there’s anything else you feel like you want to share.

Tara: I will say this one little thing, but it has to do with Rosángela because we talked the other day and I was telling her that I was coming out of a very busy period. I was tired and I didn’t know what to do with myself, like a lot of artists when their lives are very chaotic and intense, and then [there’s] nothing. She was like, “Oh, you’re like a sea lion! They’re active in the sea and doing all this stuff but when it’s time for them to rest, they go onto the beach and they just lay there.” I was so inspired by that image of having so much capacity in the water and then being back on earth and sleeping, which feels appropriate because I need to rest up before I head back into the water and do whatever sea lions do.

Rosángela: In these times, we are saturated with so much information to take in. It’s constant. If you’re taking in information all the time, it’s pretty difficult to manage to put something out. You have to enter yourself first. We need space to be able to listen to ourselves and we need space to be able to understand what we want to say to the world. And we need to rest. Like a lot of rest. The do-nothing kind of rest. Because in those spaces we begin to breathe, feel, perceive what we need.

Header Photo Credits:

Photo of Rosángela Pérez Molero by Kuámasi González; photo of Tara Kannangara by Brittany Farhat.

[ID: Tara, a brown woman with long brown hair, smiles. She is wearing a pink beanie and leaning against a wall in front of framed artwork.]

Tara Kannangara

She // Her // Hers

Toronto, Ontario

Tara Kannangara is a second-generation Sri Lankan-Canadian musician using wild trumpet melodies, searing guitar lines, lush synths, and piercing lyricism to blend genres and cultures as she explores the realities or absurdities of white excellence and the triumph of being an outsider. Growing up in Chilliwack, British Columbia, Kannangara studied classical piano and voice from an early age, and she later pursued classical trumpet and voice at the University of Victoria and jazz and improvised music at the University of Toronto. She is a JUNO-nominated musician and has been featured on CBC’s The Signal, The Sunday Edition, and NPR Music “Tiny Desk Concert “with Lido Pimienta. Her work has been presented at major festivals across North America including the Montreal Jazz Festival, DC JazzFest, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Kannangara currently teaches at Humber College in Toronto.

linktr.ee/tarakannangara

Instagram: @tara.kannangara

[ID: Rosángela, a woman with light skin and wavy dark brown hair, smiles warmly into the camera. She wears a red cardigan layered over a patterned shirt and tan sweater.]

Rosángela Pérez Molero

She // Her // Hers

Buenos Aires, Argentina and Maracaibo, Venezuela

Rosángela Pérez Molero, a Venezuelan migrant woman, is a violinist, composer, improviser, performer, sound artist, music therapist, and educator. Pérez Molero resides in Argentina, she is currently investigating themes of migration, tenderness as a dimension, the construction of the body, and sound space and its logics in her work. She positions listening as an existential position and an artistic event, and she uses free improvisation as a paradigm for the investigation of the “sonic being.” As a violinist, Pérez Molero specializes in experimental music. She is part of the musical duo Moiras with pianist Cateri Muro, and her performative work poses the body as an instrument that generates sound, movement, and connection.

rosangelaperezmole.wixsite.com/artist

Instagram: @serimprovisando