“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” —Octavia Butler

25-30 minute conversation, or the time it takes to look through old family photos.

![]()

A CONVERSATION WITH GWEN LASTER AND KAVITA SHAH

In this conversation between Gwen Laster and Kavita Shah, they delve into the concept of shedding ancestral baggage through their musical journeys. Laster draws inspiration from her own experiences, expressing how ancestral baggage can be a pathway for artists to venture into creative realms. Shah shares her struggle against imposed expectations, pushing her to reclaim her relationship to vocal freedom. Both musicians find healing in vulnerability and emphasize the significance of curiosity as a driving force for artistic expression.

As improvisers, we respond musically to who we are, where we come from, and where we are going for the adventure of landing somewhere unknown.

Luz Maria Orozco: Gwen, In your Anthology writing piece, you mentioned the concept of letting go of ancestral baggage. Do you bring this idea into your music and performances? And if so, has the process of letting go changed as music has become a part of it?

Gwen Laster: Yes, the phrase ancestral baggage shows up through my music and performances. The Anthology writing was inspired by my collaboration with Dafna Naphtali where we both had lost our fathers recently. Letting go of ancestral baggage surfaced creatively as an approach rooted in tradition and nurtured into sounds of freedom, storytelling, and adventure. Letting go feels so common amongst artists who want to celebrate their uniqueness. It’s the creative foundation I tap into when I’m composing or improvising. I feel like it’s what creatives do. As improvisers, we respond musically to who we are, where we come from, and where we are going for the adventure of landing somewhere unknown. Feeling comfortable and trusting enough to listen and respond freely will, for sure, take the musical conversation somewhere new.

I’m also becoming intrigued by composers who create their own vocabulary utilizing visuals and graphics. For me, this is another process of my music-making that is inspired by letting go and changing the platform by which I create and musicians conceive. I think about letting go of old ideas and the way I may have composed my last work. I allow my inspiration to create this path of thinking from a different platform that will hopefully make an interesting paradigm to work from. It always trickles down into things like time signatures or the tonality. What kind of melodic ideas am I coming up with? What kind of harmonic structure am I thinking about that’s different from what I just did? Why don’t I try putting together some different instruments that are gonna create some different colors and some different textures?

To have all types of music on the same playing field, that was home for me. As a child of immigrants, it was in that multifaceted place where I discovered myself.

Kavita: It’s so nice to hear you talk about your process, Gwen. It’s interesting to already know [you] and your music a bit, and then get to hear some of the things you’ve been thinking about in your work. A lot of that resonates with me. I think about ancestral baggage, or colonial baggage. Part of it is also being a woman of color in the field of music. For us, music is music. We go in the practice room, we go in the studio, we go on stage, and we do our thing. But, there’s a lot that gets projected onto us that we constantly have to walk through. That’s something that I’ve dealt with, whether it’s from journalists, the music industry, or different perceptions that are imposed onto you that have stopped me from finding my own freedom in the music. My relationship with music is pure, but then, all this stuff gets put onto it. This concept of “letting go” is really important, and it’s nice to hear you talk about that. It’s definitely a challenge.

I’ve been in my career for about eleven years now. One of my challenges is letting go of the things I wanted for myself at the beginning of my career because I’ve evolved as an artist. But, I find myself wondering what happens to the younger version of myself and the goals that I once had for myself that were very real. Part of me wants to honor them, but part of me also wants to be in the present, and be able to serve my creative muses today.

M³ was actually great because, although my music is not “traditional,” the way I perform is mostly in a traditional format. I’m a singer, I have a band, and that’s to some degree how I make a living and how people know me. But I’m interested in doing soundscapes with my voice, exploring with electronic equipment, and thinking about music in different ways that don’t necessarily fit on a stage or in the format that I tend to find myself in.

I got to explore that with M³. It’s empowering to see other women like you, Gwen, who make music in different ways. To know that there’s no one right way and that these different parts of my being can coexist. It doesn’t have to be one or the other.

Gwen: It’s interesting that you talk about different parts that coexist together, and genres or styles that we play that have different influences. That happens by default to somebody, like myself, who was classically trained on your instrument. You come to this point where you want to expand and realize that [a European trained violinist], is not going to be the first instrument to be considered in any improvised setting you want to play with. So by default, you end up being a band leader?! That’s sort of how it happened with me.

For many years I was playing in orchestras, but somehow that didn’t feel like my real career. That just felt like work. I felt like more of a freelancer. When you start trying to create your own work, it becomes a different kind of career that requires you to be a lot more detailed and transparent.

[ID: A girl with brown skin and dark brown hair stands at a microphone in a white boat. Behind her, a man looks down at the acoustic guitar he is playing.]

Kavita: Thank you for saying that. I grew up singing in a professional children’s choir in New York, The Young People’s Chorus of New York City, and we sang all different styles. We would go sing an opera in Carnegie Hall and then go to a Black church in Harlem. We sang in over thirty languages, folk music, and pop. Individually, I studied classical piano and voice, first classical, then jazz. So, my musical and aural education was strong in contemporary classical music, but also diverse in that it encompassed many different and folkloric art forms.

To have all types of music on the same playing field, that was home for me. As a child of immigrants, it was in that multifaceted place where I discovered myself. I learned, “Hey, this [multiplicity] can be music. This can be a way to live.” I’ve been trying to find that for myself ever since.

What you said about being a band leader is similar [for me] because as a singer, I’m not going to get hired by others except to do very commercial things that are maybe not what I want to do. Of course, there are times I get hired to do really cool instrumental vocal stuff, which I love, but it doesn’t happen often.

The nature of being a creator is that we have to generate our own projects and our own things as band leaders. My projects still vary quite a bit between jazz and modern jazz, contemporary classical to world music. I don’t like these labels because it’s all one continuum and it’s all part of who I am. So, like you, I’m committed to exploration, but it mostly happens under the banner of my own projects as a band leader.

Gwen: It’s great that you grew up with that experience as a singer. To sing in that environment and then be doing your classical piano, it sets the tone for you. It is so much better than just having just one genre, or working with educators who are marginalizing a particular kind of music and making it unreachable for the general population. I feel grateful that I grew up within that [cross-cultural] environment, too.

Kavita: It’s still something that I’ve had to deal with in the industry or in my jazz education: dealing with people who marginalize a particular kind of music. Some of that mentality you’re talking about is still dominant. It’s part of my job, your job, and all of our jobs as artists, to hold on to that flame that drew us into a life in music. [To hold onto] that special experience, our values, and find a way to forge ahead and stick to them and stay true to them.

[ID: A professional portrait of a Black man smiling widely. He is dressed in a suit with a hat and a patterned tie.]

Luz: I would love to move on to asking you both questions about the video pieces that you did with the other artists in the M³ cohort. Gwen, the video piece that you worked on with Dafna Naphtali, “Wake me when it’s green,” I wanted to know how you approached composing the spoken words and violin elements to create the unique blend of somberness and optimism in the piece.

Gwen: Well, thank you for interpreting it like that. After Dafna and I met, we both realized we had just lost our fathers the same year. In addition to us talking about our fathers, I also mentioned [to Dafna] about a very close friend of mine, an opera singer, who lost his mother. He had shared this funny story about how his mom used to drive them to these music lessons every week. Like everybody’s parents would do, right? She would just be so exhausted that when she got to the traffic signal, if it was red, she would just take a nap, and tell the kids, “Wake me when it’s green.” When I told Dafna about that, she said, “You know, I like that, that’s funny. We should name our piece that because it’s kind of all about people that have moved on and have influenced us.”

So, that’s where the title “Wake Me When it’s Green” came from: me just describing my father. It was a situation where I used to see him on weekends because he and my mother separated very early on and I didn’t really grow up with him [otherwise]. The melodies came from Dafna and I sharing ideas. I would say, Dafna was probably my first collaboration that was so detailed yet organic. What I enjoyed about her and felt so comfortable with was that she sent me ideas, they were just so raw, so open, and so minimal. I was like, “Yeah, off to the races. I’m just gonna send in really what’s coming through and I’m not going to worry about it. I’m not going to worry about how incomplete or complete my idea sounds. I’m just gonna send it and it’s gonna work out.”

Between us initially sending ideas back and forth virtually, we also had the opportunity to actually get together because we’re both in New York and Dafna has a studio in her house. We had one long recording day in person, and then we did a few virtual [recordings]. Once I heard what she had, some ideas came to me about what she had laid down for our groundwork. I started seeing her family pictures and then I started putting my family pictures in there. We just started comparing stories; that’s how it all came together.

Kavita: Do you feel it was healing for you?

Gwen: The goal for me [during M³] was to be more expansive and let go of old habits, old ways of presenting, conceiving, and creating music. I said from the beginning when I met with Dafna, “I want to do some spoken word.” Part of my goal was to write good stories and write some songs, just simple things like that. I felt like it was healing to talk about my father. All of it. The good, the bad, and the ugly. Just, getting it out.

Kavita: My father was in my piece too.

Gwen: Oh!

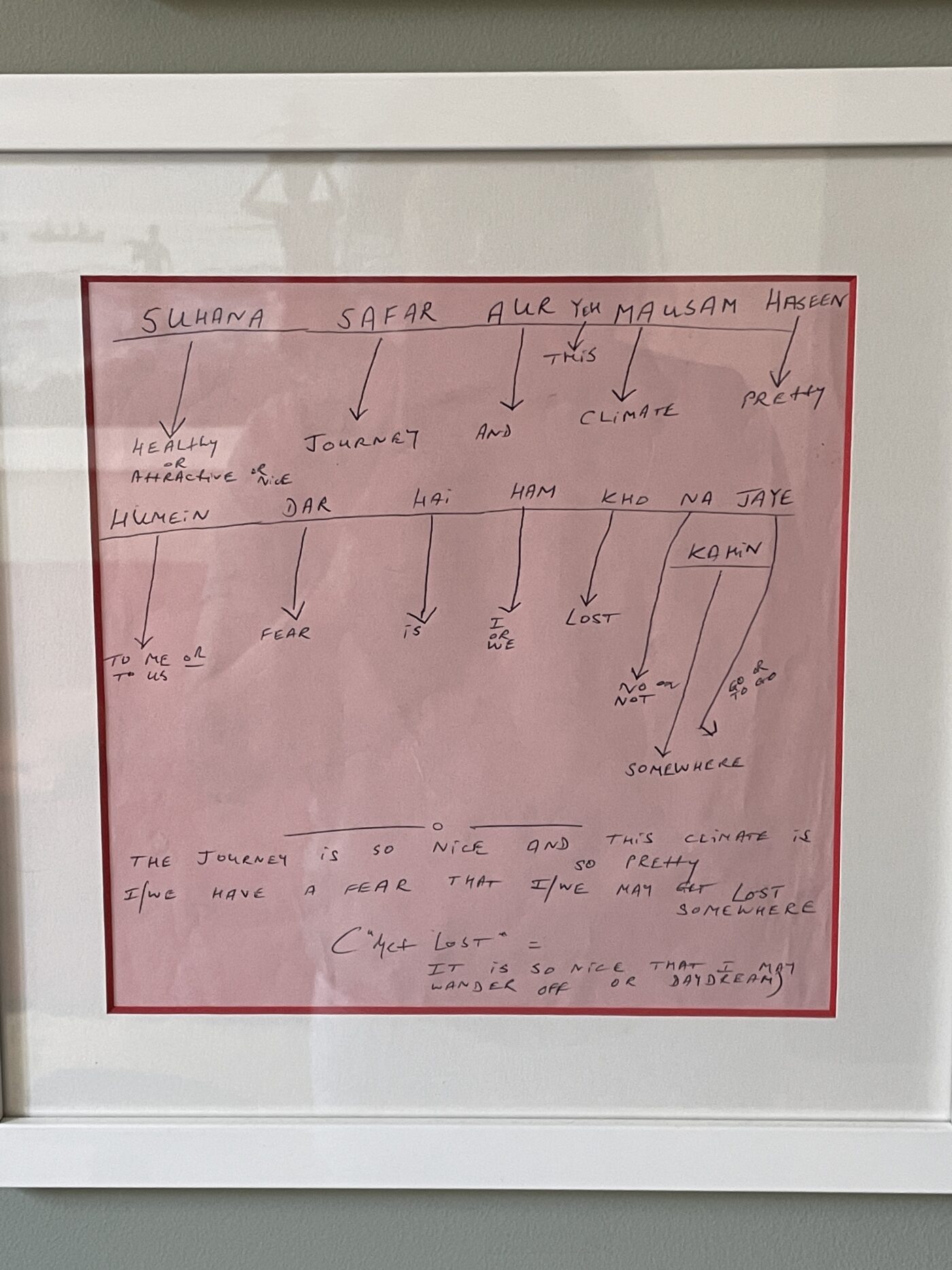

[ID: A framed document featuring a translation of the lyrics of “suhana safar aur yeh mausam haseen” from Hindi to English. The lyrics are diagrammed using pen on pink paper.]

Those little childhood things stay with you. They come out of this time when you’re idle, when you have time to dream, and those memories are sort of etched in.

Kavita: We did a series of miniatures about three cities that were important to us. One was New York, because we had both lived in New York. We realized we had both also lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, because we both studied at Harvard. There was an initial idea to do that, too, but it merged into New York, which we set to a poem by Lola Ridge called “East River” written a hundred years ago. Lola was also an immigrant from Australia. Then, we did one for each of our hometown cities. I’m born and raised in New York, but my parents and grandparents are from Bombay. [My commission partner] Zeynep grew up in Istanbul.

I lost my dad twenty years ago, when I was eighteen. As a child, I went to India a lot in the summer, but then I didn’t go from ages ten to twenty. So the memories I have of India with my dad and family, they’re very precious. It was a time of freedom because I was this over-scheduled New York kid and then I’d go to India and there was no camp, no structure. There were these gorgeous monsoon rains. It was a lot of idle time with my grandparents, playing sports, playing with kids downstairs in the compound, and playing with bugs. My memories [of India] are of snails. Fireflies. (Laughter). Those little childhood things stay with you. They come out of this time when you’re idle, when you have time to dream, and those memories are sort of etched in.

So in the second miniature piece about Bombay, I wrote a poem about those really deep memories of childhood, the city, and the sounds. I have this framed piece of paper on my wall that my dad had written his favorite Hindi song on. It’s called “Jeena Yahan Marna Yahan.” He translated the lyrics, and first he translated them literally — he was a really good writer and a poet — but then he gave this very beautiful interpretation of what the lyric meant to him. He says here, “The journey is so nice and this climate is so pretty, I have a fear we may get lost somewhere.” So, I put that in at the end of the poem [in our commission]. And Zeynep set these beautiful synths to it.

I also [interpreted] it as, he was afraid to get lost in his own life. To say, “Oh, I have a fear that we may get lost.” This is the worst nightmare, especially for the immigrant parent, fear of the unknown. But it’s also a blessing he is offering me; by writing that down, he’s saying, “I couldn’t do this, so you get lost, you enjoy this. I want you to enjoy your life and I want you to explore.” There’s a little part on the paper where he translates exactly what he means: “Get lost.” Meaning: it is so nice that I may wander off or daydream. When I found it recently, I cherished it because I realized he was giving me permission to daydream, which is something we all need to do as artists. It’s very important.

It’s interesting, Gwen, that my dad made his way into our piece, too. It’s interesting that we all went to those early places or places we don’t always go in our day-to-day work. It was an invitation and an opportunity to go there. With many other [M³ artists] and their pieces, you see a lot of family videos and footage. There’s this space to go deeper, more personal, and more vulnerable.

[ID: A young girl sits between an older man and woman at a table covered with dishes, as though they have just finished eating a meal together. All are smiling at the camera. There is a large food menu on the table.]

Gwen: The vulnerability is what people count on from us artists. People need us to be vulnerable and transparent. Healing happens when we step out of our comfort zone, and share work that is inspired in that way. People get it when they see our art and when they feel it, when they hear it, they feel like they’re in a safer space. And then it benefits us because we feel like, “Hey, I reached a milestone with my own self-discovery.”

Kavita: It’s hard.

Gwen: Yes, hard. It’s definitely hard.

Kavita: It’s hard for me to be vulnerable. I think it is a strength of mine, but it’s challenging. It goes back to some of those questions of colonialism or feeling judged. It’s this thing we carry as women of color where you have to be strong, and you have to show up and be more prepared than the next person. There’s an armor that I’ve developed to go through life because [I] don’t want to be taken advantage of, [I] don’t want to be questioned, and [I] don’t want to be doubted. That’s been necessary at some points in time and in my life. It’s a balance between those two — needing protection and letting people in because that actually is the most healing, like you said, and it’s healing for others too.

Gwen: It’s definitely healing for others.

The vulnerability is what people count on from us artists. People need us to be vulnerable and transparent. Healing happens when we step out of our comfort zone, and share work that is inspired in that way.

Kavita: How have you come to that place of vulnerability over time? Was it a challenge for you also?

Gwen: Oh yeah, it’s still a challenge, I don’t think I’m vulnerable enough. I still have this thing about being judged, not letting my walls break down in front of people, about having to be strong, or present myself in a certain way. That’s real ancestral baggage. Part of overcoming my vulnerability came from my years as an undergrad and grad student in a predominately white music school. Walking into an orchestra rehearsal or classroom as the only Black [person] felt like a weird way of being noticed yet ignored. Through following my instincts of surrounding myself in the non-Western music communities, I gained self-esteem and empowerment that allowed me to let go and develop my own creative voice. It’s a process, it’s a journey towards allowing vulnerability.

[ID: An old black-and-white photograph of a young Black woman. The photograph has been inscribed in pen on one corner.]

Luz: On that note, Kavita, in your writing you express the desire for your voice to be free from various burdens and limitations. Can you share more about what began this quest for vocal freedom?

Kavita: It’s very relevant to what we were just talking about. Being in scenarios where I feel judged, or sense that certain expectations are being placed on me even before I open my mouth. How does that affect what I sound like? This [expectation] of trying to sound perfect, trying to be perfect, and wanting to let go of that and just be true [to myself]. To find that joy of me playing with bugs. Well, I didn’t play with a lot of bugs because I grew up in New York. (Laughter). But yeah, that moment of pure curiosity as a child and that love for music that I had. If I watch videos of myself [as a child] I was singing, and in those videos I sense a pure joy of singing.

[Using our voice] is a right. It’s this beautiful thing that we have. It’s a way to express yourself. It’s a way to feel a connection with your mom, with your dad, with your family. Traditionally, it’s used within communities, within tribes to mark ceremonies, rituals, and important events. The voice is so important and so special. What’s the point of being a professional singer if I’m not enjoying it, or if it becomes about work, or it becomes about perfection? Then, it becomes a job, like Gwen was saying. My gift is something spiritual, something deeper than that. I also started to feel like I was serving other people, but I was not serving myself. When I’d go up on stage, I could show up for others but when it came to my own practice, I was not finding as much joy in it.

[Using our voice] is a right. It’s this beautiful thing that we have. It’s a way to express yourself. It’s a way to feel a connection with your mom, with your dad, with your family.

It’s about trying to get back to that first joy we have when we’re children and when we’re falling in love with the world, and our instrument, and curiosity. When you see the master musicians of any culture, any genre, they all have that childlike curiosity. That probably enables them to have longevity as musicians because that’s what people connect to and that’s the joy they radiate to others.

I wanted to get out of the Western framework of thinking about it as a job in which I have to do this, I have to do these exercises, and I have to approach it this way. Music comes from my soul, comes from my heart, and that’s number one. It’s about re-establishing that for myself and giving other people permission to also make sure that’s number one.

Gwen: Yeah, just right on. We don’t need these labels, boundaries, and limitations. Like you said, the master [musicians] — no matter what genre they’re in — when they have that curiosity, that’s what we want. That’s what it’s really all about: ongoing curiosity.

Luz: Thank you both so much. I feel like you all shared a lot of vulnerabilities here, and I’m very appreciative and grateful for that.

Header Photo Credits:

Photo of Gwen Laster by Alva Anderson; photo of Kavita Shah by Jason Gardner.

[ID: A black-and-white image of Gwen, a woman with brown skin and black hair smiles brightly into the camera holding her hands open close to her face. She is wearing dark and light colored beads around her neck and wrists.]

Gwen Laster

She // Her // Hers

Beacon, New York

Gwen Laster is a violinist, adventurous composer, socially conscious activist and educator, and scholar of African-American musical heritage. Laster’s creative influences come through the trailblazing jazz educators from her upbringing in Detroit’s public schools and her parents’ love of blues, jazz, soul, and classical music. Laster’s original compositions are informed by her passion and belief that improvisation and jazz are the highest form of expression and freedom. From there, she creates new works as a vehicle for social activism utilizing jazz (both free and inside) and improvised music from the African diaspora. She is the founder of New Muse 4tet who play music of 20th and 21st-century inspired for social change. Her sensitivity to global music informs her residencies and master classes as Artistic Director of Creative Strings Improvisers, educating young musicians. She is currently composing original music for New Muse 4tet’s next recording and “Sunny Hill Plantation”, a multimedia work based on her great grandparents’ love story on that plantation. Laster’s awards include the NEA/Jazz Fellowship, New Music USA, Mutual Mentorship for Musicians, South Arts/Jazz Roads, MPower Sphinx, Jubilation Foundation, Puffin Foundation, and Arts Mid Hudson.

gwenlaster.net

Instagram: @lastergwen

[ID: Kavita, a woman with brown skin and long brown hair looks into the camera, smiling brightly wearing silver dangling geometric earrings, a golden bracelet, and a black and white patterned dress.]

Kavita Shah

She // Her // Hers

New York, NY

Kavita Shah is a vocalist, composer, researcher, and educator who makes work in deep engagement with the jazz tradition while also addressing and advancing its global sensibilities. A lifelong New Yorker of Indian origin, Shah incorporates her ethnographic research on Brazilian, West African, and Indian musical traditions into her original repertoire. From her formal training, she draws a keen interest in complex arrangements and adventurous approaches to the voice as an instrument. She is a fierce advocate for gender and racial equity in the arts and was a founding member of the Ori-Gen Collective and the We Have Voice Collective. Shah is currently working simultaneously on a record of original music for her jazz quintet chronicling the journey to her ancestral villages in rural Gujarat, an opera about child migration, and she regularly performs her music at major concert halls, festivals, and clubs on six continents.

kavitashahmusic.com

Instagram: @cantakavita

Twitter: @cantakavita